John Bull's Schooldays

Forgotten in Tranquillity

By MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE

rT" HE first school I went to was kept by a Miss

Monday. It was round the corner from where I lived, and in a semi-detached suburban house like ours. Ellis type of school has, I imagine, now ceased to exist. There were about a dozen pupils, and we used slates to practise making letters and figures. Of Miss Monday herself I have only the vaguest memory. As I dimly recall her, she was plump and grey and kindly, with a billowing skirt and blouse, beneath which there was a whalebone structure to hold her in shape. She had a sister living with her. They were, presumably, two maiden ladies with some education and scanty means, which they augmented by the minute fees the school brought them. The establishment had a faint aura of respectability, and repre- sented a slightly superior alternative to the infants' department of the local elementary school. From my parents' point of view, the convenience was its nearness. There was only one road to cross from our house to hers, and that a cul-de-sac.

This was in 1910. We were living in Sander- stead, a village which was in process of being absorbed in the rapidly growing dormitory- suburb of Croydon. It still, however, had a few relics of its former village status, such as an ancient horse-trough, and one or two old-style country houses. Against the occupants of these my father constantly fulminated, keeping a watchful and suspicious eye on rights-of-way through their grounds to ensure that they were kept open.

From Sanderstead we moved into Croydon, to a rather larger, detached house, which had been built in accordance with my father's speci- fications. During the move I was sent away to the country for a year because of threatened tuberculosis. I stayed in a village near Stroud with family friends—a mother and a, then. unmarried daughter, from whom I received occa- sional instruction, and who caned me once or twice for 'answering back.' This offence, I may add, dogged me through my schooldays and, indeed, subsequently. I cannot recall then, or on any other occasions, feeling resentment at being physically chastised. Thus the indignation which infused a short leader I wrote on the subject years later, in the Guardian (Manchester), was decidedly synthetic. As I was a newcomer, before starting to write I put my head in through the door of a colleague's room to get the 'line on corporal punishment. Without looking up from his typewriter, he said : 'The same as capital, only more so.'

During this semi-invalid year, my education. at best, but limped along. Only in one direction did it make a great leap forward. Near where I was living there was a Tolstoyan colony, in whose foundation my father had been vaguely concerned, and to which I was taken on periodi- cal visits. Among other enlightened practices, such as holding all property in common and eschewing the us:: of money, the colonists were in the habit of baihing in the nude in a stream which ran conveniently through their land. This interesting spectacle provided me with biological instruction by the direct method. I was spared the tedium of pollen and stamens, and went straight to the heart of the matter, gazing curiously at the unclothed bodies of the matrons of the colony and with rapture at their slimmer, more shapely daughters.

When I returned to my family I was sent to a co-educational, or, in the then jargon, 'mixed,' State elementary school. This was housed in one of those solid, ungainly edifices which successive Education Acts spread over the country. There was an asphalt playground into which we charged at playtime, setting up a curious animal din, still to be heard whenever the inmates of State pri- mary schools are briefly released for recreation. The classrooms were divided by wooden par- titions, which could be opened to provide an assembly hall. Here we gathered in the morning after the roll-call had been carefully recorded in a register—a red stroke for those present and a black nought for the absent. Attendance, in those days, was one of the staff's chief pre- occupations. On it, I seem to remember, was based the amount of money made available for running the school. Those of us who failed to turn up impoverished the education of all. We began with a -hymn and a prayer. Any irregularities in pronouncing the aspirates were corrected by the headmaster while the prayer was in progress. He might make us repeat 'Our Father which art in heaven' as many as three or four times before he was satisfied with our diction. For the hymn he used a tuning-fork to get us off on the right note. One of the female teachers provided piano accompaniment.

With our morning devotions over, the par- titions were closed, and we began our studies. Classes were fifty or sixty strong, but usually included some who withdrew themselves from the proceedings and remained in a condition of blessed and total illiteracy. I learnt to read and write and add without any great difficulty, and developed a faculty which has often subse- quently held me in good stead, particularly in the army, for seeming to be eagerly engaged when actually my thoughts and attention were elsewhere. The only teacher I remember was a Miss Helen Corke--a short, eager woman in a gathered smock. I was interested to discover, later, that she was an intimate of D. H. Law- rence, at that time also an elementary school teacher in Croydon, at the Davidson Road School. She makes a somewhat lurid appearance in one of his novels—I think Women in Love— and, in a small volume, has added her gentle and moderate testimony to the numerous other accounts of him which l.awrence's associates have provided. The picture of Miss Corke, after grappling with us, her turbulent and unsatis- factory charges, laying aside her gathered smock and proceeding to grapple with Lawrence's tur- bulent and unsatisfactory Dark Unconscious is surprising and rather comical. Only on Fridays

were there afternoon devotions. Then, the par- titions were again drawn back and we assembled 1° sing 'Now the day is over.' The strains of this otherwise banal hymn have still a magical quality for me. They signified release for two Whole days.

At the age of twelve I gained a scholarship to the Borough Secondary School. The examina- tion for this included an interview with the local Inspector of Schools, a portentous Scots- man with a mop of white hair whom I held in great awe. My enemies, to my indignation, hinted that my success in the scholarship examination was due to the Inspector's desire to ingratilde himself with my father, who was an active and vociferous Labour councillor and member of the Education Committee. I hope their malignant suggestion was baseless, but honesty compels me to admit that this was the °My examination in which I ever achieved any success.

The Borough Secondary School was tem- porarily housed in a Polytechnic building. We used it during the day, but its true purpose was for evening classes. Later, our school was transferred to a building of its own. Its organi- sation was vaguely derived from that of public schools. There were four 'houses'—Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta—which, in practice, had little more than a nominal existence, as well as pre- fects, colours and other trappings reminiscent of Tom Brown's Schooldays, not to mention the Magnet and the Gem. We had a Latin motto 'Ludunt Ludite,' or 'Play the game,' invented, I Suppose, by one of the masters.

Such schools as these, paid for by the State and ardently promoted by Socialists like my father, were really preparing the way for the condition of permanent Conservative govern- runt which has now befallen us. They limped along after the older-established grammar and Public schools, cordially despised by them, but aiming at turning out a similar product. During a brief period of respectability when first I was editor of Punch, I was asked to address my old school on its annual speech day. I found that the process had been carried much further. Its name had been changed to 'Grammer' instead Of 'Secondary' school. There was even a school song, sturdily intoned. Waterloo may have been Won on the playing fields 'of Eton, but the class war was assuredly lost on the playgrounds and in the classrooms of State Secondary Schools. Social reform is the safest, strongest, surest foundation of the status quo. The old Morning which long ago disappeared, romantically tried to defend privilege; the Guardian and the 7'hnes continue to devote their energies to the More profitable task of adjusting its camouflage to suit changes in the social climate.

These were the years of the 1914-18 war. Most of the staff had been called up and were away, fighting and dying in Flanders mud. Their replacements were a curious collection of oddities ----among others, an Indian with an imperfect command of English who instructed us in Chemistry, a lady with a shrill, genteel voice for whom we wrote compositions, an elderly Mathematics master with rather obviously dyed hair and a frenzied moustache who desperately flung chalk at us when, as frequently happened, we failed to get his point. I can remember them all, in their tattered gowns—this one genial, that one erudite, and this other seemingly malignant as he sat, dark and glowering, while one stumbled over French irregular verbs.

• I rode to and from school on my bicycle. The very air was full of the hysteria of war. There were old boys who appeared, resplendent in their uniforms. We ourselves had a school cadet corps which we were compelled to join. The headmaster was in charge of it, with the rank of a major, and shambled along at the head. of us when we had occasion to march through the streets, his uniform, as even my ignorant eye could detect, in strange disarray.

When, later, at Cambridge and elsewhere, I got to know the products of public schools, the thing that struck me about them was their pas- sionate• entanglement in their schooldays. At first I rather envied them this, and wished that too, had memories of famous cricket matches, a private, exclusive slang, and all the other out- ward and visible manifestations of belonging to an inward and invisible elite, self-contained and economically and socially advantageous. On further consideration, however, I changed my attitude. It seemed to me that the great ad- vantage of the sort of education I had was precisely that it made practically no mark upon those subjected to it. Scholastic and other de- ficiencies were more than compensated for by the fact that one's first vivid impressions of life were provided, not by a closed and essen- tially homosexual community of schoolboys under the direction of masters who had them- selves been through the same process, but by men and women actually living and earning their livings. How much I preferred the ribald, noisy, dangerous world to any walled garden, however elegantly arranged and full of summer fragrance! No one ever seems to forget Eton. I easily forgot my Borough Secondary School.

In our spare time we roamed- the Croydon streets, gazed wistfully at dazzling girls playing tennis in public recreation grounds, and hoped that the war would stretch on until we, too, could participate in its glories and adventures. I even, on one occasion, went so far as to present myself at a recruiting office, tremulously insist- ing that I was in my nineteenth year. The NCO in charge was sympathetic, but sceptical. He told me to return with a birth certificate.

Games were voluntary. I have practically never played football or cricket, for which I am profoundly thankful. Even to watch these games is for me an anguish of boredom. The first conversational exchange I had at a Punch lunch occurred when one of the staff asked me whether I was interested in cricket. I replied briefly: 'No.' This total absence of a games mystique eliminated hero-worship. There was no Steerforth at my school. My days have not been haunted by any lingering adoration of some god- like athlete, compared with which adult fleshly love seems coarse and demeaning. Plato did not come into our lives. Our adolescent sen- suality was directed exclusively towards girls, whose persons, as we grew older, we ventured to explore, in scented cinema darkness, or beside blackberry bushes under the August sun. I had never even heard of homosexuality until I went to Cambridge. The idea of embracing, or being embraced by, persons of one's own sex when females were available seemed to me highly bizarre.

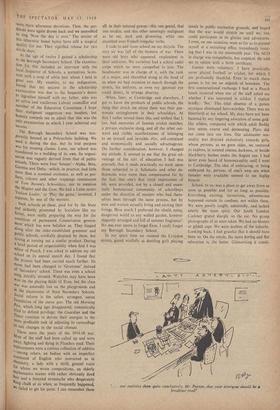

School, to us. was a place to get away from as soon as possible and for as long as possible. Everything exciting, mysterious, adventurous happened outside its confines, not within them. We were poorly taught, admittedly, and lacked utterly the team spirit. Our South London Cockney grated sharply on the ear. No group photographs of us were taken. We had no blazers or gilded caps. We were urchins of the suburbs. Looking back, I feel grateful that it should have been so. On the whole, the more boring and flat education is, the better. Glamorising it consti- our statistics show quite conclusively, Mr. Paxton, that your detergent should be a breakfast food!' tutes a kind of brain-washing. It fixes the victim neatly into ways of behaviour and of thought from which escape is difficult, and, in any case, a kind of treason. I, personally, have no com- plaints on this score. When I embarked upon the arduous, but infinitely exhilarating, pursuit of the meaning of things, it was from the bottom of a stony hillside with no golden memories of lost innocence about my head, no nostalgia for a vanished schooldays world about my heart.

Previous page

Previous page