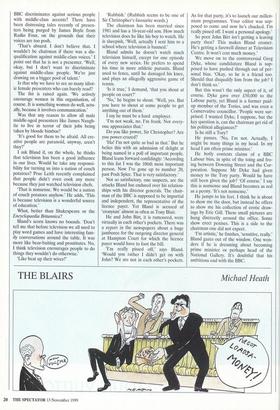

BLAND BLOWS A FUSE

Petronella Wyatt asks the BBC chairman about the alleged failings of his Corporation, and feels his wrath

IN THE hall of Broadcasting House in London is a plaque that reads 'Deo Omnipotenti Templum Hoc Artium' (To almighty God is dedicated this temple of the arts'). These days, this seems a grandiose, even pathetic, ambition. The BBC is assailed on all sides by accusations of inefficiency, profligacy, dumbing down and, very damagingly, of cronyism in the recent appointment of Greg Dyke as the new director general. Dyke is a personal friend of Sir Christo- pher Bland, the chairman of the BBC's board of governors since 1994. So is John Bin, the outgoing director general. Senior figures in the BBC had expressed worries to me that Bland runs the company as a personal fiefdom, rather than in the inter- ests of the licence payers whose burden is now £101 per person a year. (From next year, though, canny Gordon Brown will pay your licence if you are over 75.) I had set off to ask Bland what he thought of these attacks. It had occurred to me that it might be time we abolished the BBC. With so many cable and satellite channels, as well as Channel 4 and Carl- ton, why not dispatch Auntie to a rest home, now that her eyesight and grip seem to be failing? Why not replace Television Centre with a large video-film library?

These thoughts were crossing my mind as I made my way up, in a lift of rather Pompous design, to Bland's office. Sir Christopher was born in Northern Ireland and educated at Oxford before joining the Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards. He held senior posts at Century Hutchinson and LWT, acquiring a luxurious house in France and a trophy wife. Bland has also dabbled in Tory politics as a councillor. At 61, he has a reputation for being an Angry Middle-Aged Man. One has even heard that he shouts at people on tennis courts.

At first sight there was not much sign of a congenital tendency to anger. His office In a soothing melange of white — only a few pink, plumped-up cushions interrupt- ing the snowiness of its interior. Sir Christopher was upholstered in a close-fit- ting blue shirt and a blue and white spot- ted tie. He smiled at me amiably, though the after-effect wasn't quite right, like a sharp taste after a sip of claret.

I decided to put him at his ease with a little joke. Sir Christopher, I asked, has the surname Bland been a hindrance to a career in broadcasting? He looked at me as if I were deranged. Then, in a voice scary with sarcasm he shot back, 'Sure, I might have gone really far otherwise.'

Okay, okay. Bland was obviously a man who liked his conversation heavy. So then, I began portentously, how did he see the future? With so many competitive chan- nels, many of them providing gripping entertainment, what did the BBC have that the market didn't?

Sir Christopher puffed up his chest like a blue canary: 'We are still a trusted guide to quality standards.'

Nonetheless the BBC is on the prongs of a Morton's Fork. The company needs to jus- tify the licence fee by holding big audiences; but in struggling to hold big audiences it is 'dumbing down' — and so jeopardising the very claim to public-service broadcasting-on which the licence fee is based.

'I agree that is a big danger. That is a tightrope we have to walk skilfully along. But a good example of our skill is Walking with Dinosaurs — a programme that is both quality and popular.' 'But that's a one-off,' I point out. As I do so I can see Bland beginning to become angry. It is like watching the Incredible Hulk. His arms seem to bulge and vibrate. 'Rubbish. Over the millennium we are doing Richard Eyre on the English stage and a series with Simon Schama on history.'

That sounded to me like a token don, and luvvies droning on: nothing that Carl- ton or Channel 4 couldn't do. Was he not worried that Carlton was making inroads into the BBC's quality programming, with series such as Hornblower, World War Two in Colour and Frenchman's Creek?

Bland raised a clenched fist in the air. 'Certainly not. If we set a benchmark for quality, we have to be pleased when others aspire to it. It means we have made broad- casting a better place.'

But perhaps the BBC has done as much as it can; perhaps it is time for it to step aside. The idea of a state television station paid for by the populace seems outmoded in our post-Thatcher society, doesn't it? Could he see people still paying a licence fee in 20 years time?

'I don't know, Ten years, yes. But more, only maybe. But if you want what the BBC does, it's the least worst way of providing it. Sky's package deal of £340 makes £101 for the licence fee look quite cheap.'

The difference is that with Sky the punter has a choice whether to pay or not.

But all those little old ladies in Humber- side, whose only solace and comfort is tele- vision, have to fork out a large sum even if they never watch the BBC. Bland had no reply to this one but, as Boswell said of Dr Johnson, when his pistol misfires he knocks you down with the butt end of it.

He began to shout, 'Nonsense, it's not a large sum.'

'It is for a little old lady,' I said.

'I still don't think so. Licence-fee evasion is now at its lowest level at only 5.8 per cent.'

'That's because you terrorise everybody with those disgraceful things on the Under- ground that "name and shame". And quite often you've made a mistake and the per- son didn't even own a television.'

Bland became evasive: 'Well, there are mistakes — but not very many, and we only use prosecution as a last resort. Basically it works out pretty cheap per hours of pleasure.'

Many would claim that the pleasure is not as edifying as it used to be. Why have they moved every serious programme to the early hours of the morning? Why are Question Time and Newsniglu only on after many professional people have gone to bed?

At last the chairman makes a concession. 'I am looking at that, actually,' he told me.

Question Time is on much later than I would like. But look here, we do take news seriously. We didn't move our flagship news programme for a peak-time movie like ITN did.'

On a similar point, can he deny that the BBC discriminates against serious people with middle-class accents? There have been distressing tales recently of presen- ters being purged by James Boyle from Radio Four, on the grounds that their voices are too posh.

'That's absurd. I don't believe that. I wouldn't be chairman if there was a dis- qualification against middle-class voices.' I point out that he is not a presenter. 'Well, okay, but I don't want to discriminate against middle-class people. We're just drawing on a bigger pool of talent.'

Is that why we have to see so many idiot- ic female presenters who can barely read?

The fist is raised again. 'We actively encourage women in this organisation, of course. It is something women do well, actu- ally, because it involves communication.'

Was that any reason to allow all male middle-aged presenters like James Naugh- tie to live in terror of their jobs being taken by blonde bimbos?

'It's good for them to be afraid. All cre- ative people are paranoid, anyway, aren't they?'

I ask Bland if, on the whole, he thinks that television has been a good influence in our lives. Would he take any responsi- bility for turning us into a nation of couch potatoes? Prue Leith recently complained that people didn't even cook any more because they just watched television chefs.

'That is nonsense. We would be a nation of couch potatoes anyhow.' He adds, 'This is because television is a wonderful source of education.'

What, better than Shakespeare or the Encyclopaedia Britannica?

Bland's scorn knows no bounds. 'Don't tell me that before television we all used to play word games and have interesting fam- ily conversations around the table. It was more like bear-baiting and prostitutes. No, I think television encourages people to do things they wouldn't do otherwise.'

'Like beat up their wives?' 'Rubbish.' (Rubbish seems to be one of Sir Christopher's favourite words.) The chairman has been married since 1981 and has a 16-year-old son. How much television does he like his boy to watch. He is sheepish, 'Well, actually I sent him to a school where television is banned.'

Bland admits he doesn't watch much television himself, except for one episode of every new series. He prefers to spend his time in more athletic pursuits. Bland used to fence, until he damaged his knee, and plays an allegedly aggressive game of tennis.

'Is it true,' I demand, 'that you shout at people on court?'

'No,' he begins to shout. 'Well, yes. But you have to shout at some people to get anything out of them.'

I say he must be a hard employer.

'I'm not weak, no. I'm frank. Not every- one appreciates that.'

Do you like power, Sir Christopher? Are you power-crazed?

'Ha! I'm not quite as bad as that.' But he belies this with an admission of delight at being named in a poll of important people. Bland leans forward confidingly: 'According to this list I was the 106th most important person. Now I've gone up to number 20, past Posh Spice. That is very satisfactory.'

Not so satisfactory, one suspects, are the attacks Bland has endured over his relation- ships with his director generals. The chair- man of the BBC is supposed to be impartial and independent, the representative of the licence payer. Yet Bland is accused of 'cronyism' almost as often as Tony Blair.

He and John Birt, it is rumoured, were virtually in each other's pockets. There was a report in the newspapers about a huge jamboree for the outgoing director general at Hampton Court for which the licence payer would have to foot the bill.

'I'm really pissed off,' says Bland. 'Would you rather I didn't get on with John? We are not in each other's pockets. As for that party, it's to launch our millen- nium programmes. Your editor was sup- posed to come and now he's chucked. I'm really pissed off. I want a personal apology.'

So poor John Birt isn't getting a leaving party then? This makes Bland crosser. He's getting a farewell dinner at Television Centre. It won't cost much money.'

We move on to the controversial Greg Dyke, whose candidature Bland is sup- posed to have pushed through out of per- sonal bias. 'Okay, so he is a friend too. Should that disqualify him from the job? I don't think so.'

But this wasn't the only aspect of it, of course. Dyke gave over £50,000 to the Labour party, yet Bland is a former paid- up member of the Tories, and was even a Conservative councillor. 'People were sur- prised: I wanted Dyke, I suppose, but the key question is, can the chairman get rid of his political allegiances?'

Is he still a Tory?

He pauses. 'No, I'm not. Actually, I might be many things in my head. In my head I am often prime minister.'

He hotly contests claims of a BBC Labour bias, in spite of the toing and fro- ing between Downing Street and the Cor- poration. Suppose Mr Dyke had given money to the Tory party. Would he have still been given the job? 'Of course.' I say this is nonsense and Bland becomes as red as a peony. 'It's not nonsense.'

He jumps to his feet. I think he is about to show me the door, but instead he offers to show me his collection of erotic draw- ings by Eric Gill. These small pictures are hung discreetly around the office. Some show erect penises. This is a side to the chairman one did not expect.

'I'm artistic,' he finishes, 'sensitive, really.' Bland gazes out of the window. One won- ders if he is dreaming about becoming prime minister or perhaps head of the National Gallery. It's doubtful that his ambitions end with the BBC.

Previous page

Previous page