Finding and losing a voice

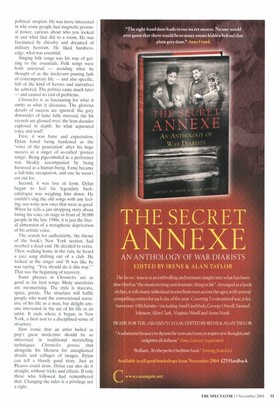

Edward Smith CHRONICLES by Bob Dylan Simon & Schuster, £16.99, pp. 256, ISBN 0743230760 (c) £14.99 (plus £2.25 p&p) 0870 800 4848 What does it take to turn artistic talent into its full creative expression? Then, once you've found your authentic artistic voice, how can you stop critics and followers over-defining it until you feel penned-in to the point of paralysis? And if you finally lose your voice altogether, how do you find it again? Bob Dylan's brilliant autobiography Chronicles invites us to share that creative voyage, to listen to his emerging artistic voice. Singing is only a small part of the story. It is much, much bigger than that.

The story starts as abruptly and arrestingly as one of his own ballads, when the 20-year-old Robert Zimmerman arrives in New York in 1961 wanting to sing folk songs. Where he came from is unimportant to this particular story. All we need to know is that he had talent and boundless self-confidence. He knew he had 'it'. I le just wasn't quite sure what 'it' was. To discover that, he needed a context, a bohemian education and some good luck. New York provided all three.

It was the perfect setting; coffeehouses, smoky clubs, night-long parties, personal reinvention, the buzz of the cutting edge. He evokes the scene so well, we could be walking with him into a cold easterly breeze coming off the Hudson river. He fitted right in — sleeping on sofas, searching for Woody Guthrie records, tuning into compelling characters, tuning out of what bored him.

He played and sang wherever he could, happier to practise with an audience than alone. He was given the keys to eccentric apartments with quirky libraries. He opened books in the middle, and if he liked them went back to the beginning. A relentless curiosity coexisted with a determination not to go under to new influences. It was his voice he was looking for, not anyone else's.

He looked around at who he admired, worked out what they had and how he might acquire it without losing his integrity. The young Dylan was not some sappy political utopian. He was more interested in why some people had magnetic person al power, curious about who you looked at and what that did to a room. He was fascinated by chivalry and dreamed of military heroism. He liked hardness, edge, what was essential.

Singing folk songs was his way of getting to the essentials. Folk songs were both universal — avoiding what he thought of as the irrelevant passing fads of contemporary life — and also specific, full of the kind of heroes and narratives he admired. The politics came much later — and caused no end of problems.

Chronicles is as fascinating for what it omits as what it discusses. The glorious details of success are ignored, the gory downsides of fame fully stressed, the hit records are glossed over, the lean decades explored in depth. So what separated voice and soul?

First, it was fame and expectation. Dylan hated being burdened as the 'voice of the generation' after his huge success as a singer of so-called 'protest songs'. Being pigeonholed as a performer was bleakly accompanied by being harassed as a human being. Fame became a full-time occupation, and one he wasn't cut out for.

Second, it was loss of form. Dylan began to feel his legendary backcatalogue was weighing him down. He couldn't sing the old songs with any feeling, nor write new ones that were as good. When he tells a jaw-dropping story about losing his voice on stage in front of 30,000 people in the late 1980s, it is just the literal dimension of a metaphoric deprivation of his artistic voice.

The search for authenticity, the theme of the book's New York section, had reached a dead-end. He decided to retire. Then, walking home in the rain, he heard a jazz song drifting out of a club. He looked at the singer and 'It was like he was saying, "You should do it this way." That was the beginning of recovery.

Some phrases in Chronicles are as good as his best songs. Many anecdotes are mesmerising. The style is staccato, spare, poetic. The structure will baffle people who want the conventional narrative of his life as a man, but delight anyone interested in the arc of his life as an artist. It ends where it began, in New York, a final nod to a disciplined sense of structure.

How ironic that an artist hailed as pop's great modernist should be so interested in traditional storytelling techniques. Chronicles proves that alongside his likeness for unexplained details and collages of images, Dylan can tell a bloody good story. Just as Picasso could draw, Dylan can also do it straight, without tricks and effects. If only those who followed had remembered that. Changing the rules is a privilege not a right.

Previous page

Previous page