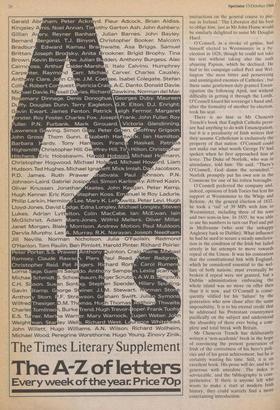

The discarded Liberator

Stan Gebler Davies

The Great Dan: A Biography of Daniel O'Connell Charles Chenevix Trench (Jonathan Cape £10.95)

Scum condensed of Irish bog, Ruffian, coward, demagogue!

The Times got Daniel O'Connell wrong by a wide margin. He was, on the Contrary, a landed gentleman jealous of the rights of property, a duellist contemp- tuous of mobs howling for his blood and an accomplished parliamentarian. His family, of the Gaelic aristocracy, held on to estates in Kerry during penal times by leasing them from Protestants, bolstering their income with a lively trade in smuggling. An uncle was a general of Louis XVI's Irish Brigade who, having no taste for revolu- fion, transferred his allegiance to George III in 1789 and raised him a brigade. In it, the younger brother of O'Connell, edu- cated with him at St Omer and Douai, Perished of yellow fever in the West Indies.

The O'Connells gave up the Jacobite cause at the earliest opportunity and were later appalled at the prospect of Jacobin- ism being imported into Ireland. Devout Catholics, they protested (sincerely) that Only the disabilities imposed on their reli- gion prevented their allegiance to the Crown and when they were removed, happily swore loyalty. Daniel, author of Emancipation, could claim credit for hav- ing removed the greatest of these disabili- ties, but credit he no longer gets from his Irish co-religionists.

No one, as the author remarks, proposes to tear down the numerous statues to the Great Liberator or re-name the several dozen O'Connell Streets. Neither is his name invoked in speeches. As the model of a hero, he is entirely out of fashion. There are several reasons why this should be so. The present-day Irish nationalist intel- ligentsia is almost entirely collectivist, but O'Connell was an early opponent of trades unions. Having witnessed both the French Revolution and the rising of 1798, he thought political violence both futile and evil, an opinion which runs counter to the cult of 1916. Lastly, having been fostered by peasants in the old Gaelic tradition and learnt Irish as his first language, he dismis- sed it as unsuited to modern intercourse and was all for its replacement as the language of the people by English.

An immensely successful banister on the Munster circuit, O'Connell was noted for the facility with which he bullied oppo- nents and wore down witnesses. These techniques he successfully adapted to poli- tics. 'There is,' he wrote, 'a moral electric- ity in the continuous expression of public opinion concentrated on a single point, perfectly irresistible in its efficacy.' What he meant by this was that Irish Catholics, who could not gain their objectives by insurrection, might yet get their way by boring, exasperating and baffling the Eng- lish into concession. (He was quite proud of his ability to bore the House of Com- mons.) In pursuit of Emancipation, O'Connell and his allies inundated the Westminster parliament with up to 12,000 petitions a year, to which were added remonstrances and loyal addresses from every parish. It is no wonder that, under such bombardment, successive Viceroys and Chief Secretaries veered from coercion to weary compliance and back again. (The present Eire administration has not forgot- ten the lesson. Remonstrances are address- ed daily to London, and the report of the New Ireland Forum is surely the most voluminous and tendentious petition ever presented to Parliament.)

Then, as now, one must feel sorry for Englishmen sent as politicians into Ireland. O'Connell made monkeys of them. How could the Marquess of Anglesey, a forth- right soldier man, be expected to cope? Appointed Viceroy by Canning and left in office by Wellington, whose sec-ond-in- command he had been at Waterloo, he got no brief from either of them. At Waterloo, he had lost a leg. In Ireland he lost his way entirely.

Ought he to suppress the agitation for Emancipation or not? He was not told. 'He was the sort of Englishman,' writes Chenevix Trench, 'who, on landing at Dunleary, immediately takes a euphoric view of the Irish and is convinced that only a little goodwill is needed to solve all their problems.' O'Connell got him publicly to support his agitation. Wellington gave him the boot. 'I was in the unusual situation,' he confessed to O'Connell, 'that I had no instructions on the general course to pur- sue in Ireland.' The Liberator did his best to oblige him, just as Mr John Hume would be similarly delighted.to assist Mr Douglas Hurd.

O'Connell, in a stroke of genius, had himself elected to Westminster in a by- election in 1828, though he could not take his seat without taking also the oath abjuring Papism, which he declined. fie had in his campaign called Peel and Wel- lington 'the most bitter and persevering and unmitigated enemies of Catholics', but these same gentlemen duly granted Eman- cipation the following April, not without difficulty in getting it through the Lords. O'Connell kissed his sovereign's hand and, after the formality of another by-election, took his seat.

There is no hint in Mr Chenevix Trench's book that English Catholic press- ure had anything to do with Emancipation, but it is a peculiarity of Irish writers that they assume Catholicism is exclusively the property of that nation. O'Connell could not make out what words George IV had spoken when he first approached him at levee. The Duke of Norfolk, who was in attendance, told him: 'He said, "There's O'Connell, God damn the scoundrel.' Norfolk promptly put his own son in the Commons for one of his rotten boroughs.

O'Connell preferred the company and, indeed, opinions of Irish Tories but lent his support at Westminster to the Whigs and Reform. At the general election of 1832, he took a 'tail' of 39 MPs with .him to Westminster, including three of his sons and two sons-in-law. In 1835, he was able to use his numbers to turn out Peel and put in Melbourne (who sent the unhappy Anglesey back to Dublin). What influence he had he used to secure a steady ameliora- tion in the condition of the Irish but failed • utterly in his attempts to move towards repeal of the Union. It was his contention that the constitutional link with England, which he considered essential to the wel- fare of both nations, must eventually be broken if repeal were not granted, but a Dublin administration embracing the whole island was no more on offer then than it is now, and O'Connell is conse- quently vilified for his 'failure' by the generation who now chase after the same impossibility. It is to his eternal credit that he addressed his Protestant countrymen pacifically on the subject and understood the absurdity of' there ever being a com- plete and total break with Britain. Mr Chenevix Trench has deliberately written a 'non-academic' book in the hope of convincing the present generation of Irish of the correctness of his hero's poli- cies and of his great achievement, but he is certainly wasting his time. Still, it is an excellent book. His prose will do, and he is generous with anecdote. The index is serviceable, and the bibliography is com- prehensive. If there is anyone left who wants to make a start at modern Irish history, they could scarcely find a more entertaining introduction.

Previous page

Previous page