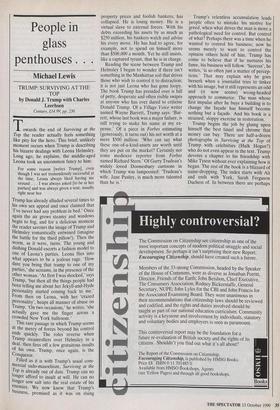

People in glass penthouses . .

Michael Lewis

TRUMP: SURVIVING AT THE TOP by Donald J. Trump with Charles Leerhsen Century, £14.99, pp. 236 Towards the end of Surviving at the Top the reader actually feels something like pity for the hero. This brief, unlikely moment occurs when Trump is describing his bizarre dealings with Leona Helmsley. Long ago, he explains, the middle-aged Leona took an uncommon fancy to him:

For some reason [writes Trump], even though I was not tremendously successful at the time, Leona always liked having me around . . . I was always asked [to be at her parties] and was always given a seat, usually right near her.

Trump has already alluded several times to his own sex appeal and once claimed that `I've never had any problem in bed.' Once again the air grows steamy and windows begin to fog, and for a delicious moment the reader savours the image of Trump and Helmsley romantically entwined (imagine the battle for the third pillow!). Then the worm, as it were, turns. The young and dashing Donald escorts a fashion model to one of Leona's parties. Leona flies into what appears to be a jealous rage. 'How dare you bring that tramp to one of my parties,' she screams, in the presence of the other woman. 'At first I was shocked,' says Trump, 'but then all the things people had been telling me about her Jekyll-and-Hyde personality started coming back to me.' From then on Leona, with her 'crazed personality', heaps all manner of abuse on Trump. 'On two occasions,' he writes, 'she actually gave me the finger across a crowded New York ballroom.'

This rare passage in which Trump seems at the mercy of forces beyond his control ends quickly. The roles reverse when Trump steamrollers over Helmsley in a deal, then fires off a few gratuitous insults of his own. Trump, once again, is the Conqueror.

Filled as it is with Trump's usual com- mercial sado-masochism, Surviving at the Top is already out of date. Trump can no longer afford to insult at will. He can no longer sow salt into the real estate of his enemies. We now know that Trump's business, premised as it was on rising property prices and foolish bankers, has collapsed. He is losing money. He is a virtual slave to external forces. With his debts exceeding his assets by as much as $250 million, his bankers watch and advise his every move. He has had to agree, for example, not to spend on himself more than $500,000 a month. Yet he still insists, like a captured tyrant, that he is in charge.

Reading the scene between Trump and Helmsley I began to wonder if there isn't something in the Manhattan soil that drives those who wish to control it to distraction; it is not just Leona who has gone loopy. The book Trump has presided over is full of petty, desperate and often risible swipes at anyone who has ever dared to criticise Donald Trump. Of a Village Voice writer named Wayne Barrett, Trump says: 'Bar- rett, whose last book was a major failure, is still trying to make his name at my ex- pense.' Of a piece in Forbes estimating (generously, it turns out) his net worth at a mere $500 million: 'Who can say what these one-of-a-kind-assets are worth until they are put on the market? Certainly not some mediocre reporter from Forbes named Richard Stern.' Of Garry Trudeau's widely loved Doonesbury cartoons in which Trump was lampooned: `Trudeau's wife, Jane Pauley, is much more talented than he is.' Trump's relentless accumulation leads people often to mistake his motive for greed, when what drives the man is more a pathological need for control. But control of what? Perhaps there was a time when he wanted to control his business; now he seems merely to want to control the opinion others hold of him. Trump has come to believe that if he nurtures his fame, his business will follow. 'Success', he writes, is so often just a matter of percep- tions.' That may explain why he goes berserk when a journalist tries to tinker with his image, but it still represents an odd and (it now seems) wrong-headed approach to commerce. The man whose first impulse after he buys a building is to change the facade has himself become nothing but a facade. And his book is a strained, sloppy exercise in restoration.

Trump begins the job by gluing upon himself the best tinsel and chrome that money can buy. There are half-a-dozen photographs in Surviving at the Top of Trump with celebrities (Hulk Hogan?) who do not even appear in the text. Trump devotes a chapter to his friendship with Mike Tyson without ever explaining how it began. The rest of the book is a blizzard of name-dropping. The index starts with Ali and ends with York, Sarah Ferguson Duchess of. In between there are perhaps ten names not recognisable to readers of People magazine. Under 'V': Vanderbilt family and Van Gogh, Vincent. Under '0': Onassis, Jackie. 'Pick the wrong name,' says the author in explaining why he named a casino Trump, 'and no matter what else you do you'll never be a hit.' (Perhaps there's a new Trump board game in this: I give you a letter from Trump's index and you guess who is listed under- neath. Pick the wrong name and I foreclose on you.) Another stratagem in Trump's bag of cheap building tricks is simply to tell us repeatedly how widely loved and admired he is. Of a trip to Brazil (a country with which he has much in common, financially) he says only that 'I found Brazil to be a lovely, if economically troubled, country. And I was surprised and delighted that children came running up to me with pencils and paper yelling, "Mr Trump, Mr Trump." ' He walks down Fifth Avenue and

about 25 perfect strangers wave and shout, 'Hi Donald,' and `How're you doing Donald,' and 'Keep up the good work.' One thing this proves to me is that the average working man or woman is a lot better adjusted and more secure than the supposed- ly successful people who stare down at them from the penthouses.

So says the penthouse dweller. And he may be right (all the best theories of human behaviour include oneself). Surviv- ing at the Top is a portrait of an ego gone haywire. The madness of the author is its dominant, if unintentional, theme. He saves the reviewer a paragraph transition by raising the issue himself. 'I'm not the same person that I was just a few years ago,' he writes early in the book, 'and the changes I've undergone are the subject of this book.' In a chapter called 'The Surviv- al Game', he suggestively offers a list of once wealthy men who died by suicide; they are, it seems, his bogey. He compares himself to Howard Hughes: As time goes on I find myself thinking more and more about Howard Hughes and even, to some degree, identifying with him. Take, for example, his famous aversion to germs. While I'm certainly not as fanatical as he was, I've always had very strong feelings about cleanliness. I'm constantly washing my hands.. .

But he is not exposing himself so much as shopping for new identities. Having tried Howard Hughes (or Lady Macbeth) on for size, he at last selects another, equally implausible shell. He tells us, in so many words, that he has discovered the futility of the possessions he calls 'my trophies'. The best known of these is perhaps the yacht, now named the Trump Princess, purchased from the arms dealer Adnan Kashoggi (see Doonesbury for de- tails). Trump devotes a chapter to the Princess identical in tone and content to the braggadocio in 'The Art of the Deal': how brilliantly Trump haggled for it, how Trump's boat is the biggest, how Trump made it better, and so on.

Then he lobs in his newly acquired knowledge of himself: But as much as I've enjoyed it until now, and as impressive as it has been to my casino customers, I think I'm giving up the game of who's got the best boat . . . It's funny how the boat seemed more appropriate to my life in the past than to my future.

It is even funnier that this decision comes at just the moment he can no longer afford the boat. There's every reason to believe that self-denial is just one more gewgaw for the Trump façade, stuck on to distract us from the quality of the workmanship. After all, the man has built a career gloating over his ability to fool others; `fool' comes second only to 'loser' as Trump's favourite epithet. The truth is more likely to be that if his real estate recovers the man will begin bragging more loudly than ever about his boat. But who then will listen? Only his ghost.

Michael Lewis is the author of Liar's Poker, Coronet, £4.50.

Previous page

Previous page