Congo Report

From KEITH KYLE THE election of Edouard Bulundwe as. Pro- vincial President in Elisabethville stripped Moise Tshombe, now convalescing in Spain, of the last trace of his official status. It liqui- dated his administration and his province, and eliminated the last rival to Leopoldville as a political pole around which a permanent Con- golese Federation could be organised. Across the river from Leopoldville, the overthrow of the Abbe Fulbert Youlou, the President of Congo- Brazzaville, has removed Tshombe's only con- siderable African patron. Still, Tshombe is resilient: he has cabled Bulundwe congratulating him and has told the press that he will re-enter politics as a candidate in the next elections, which must take place by May next year. More- over Katangese 'buffs' may be less impressed with the newness of Tshombe's successor than with the reappearance of three of the more cele- brated members of the old secessionist gang, Jean-Baptiste Kibwe, Godefroid Munongo and Charles Mutaka-wa-Dilumba, as Ministers around him. Much will depend on whether Presi- dent Kasavubu has any luck in equipping the Congo with a constitution before she has to have another election: he has summoned the Central Parliament into session for the first time in its capacity as a Constituent Assembly. It will have three texts befere it, one of them drafted by UN advisers, another by Tshombe's.

Katanga Oriental, the province of which Elisa- bethville is now the capital, is the rump of Tshombe's former 'State,' with the north, which remained loyal to the Congo but was partly reconquered by the mercenaries and gen- darmes, shorn off and a new province of Lualaba hacked out of the south-west. This latest parti- tion cuts off the Lunda, Tshombe's tribe, formerly ruled by his father-in-law and now by his uncle, from Elisabethville, and separates Kolwezi, the most up-to-date and almost wholly automated plant of the Union Miniere, from the rest of the complex in Jadotville, Elisabethville and Kipushi. All these are in Bulundwe's Katanga Oriental; Kolwezi, in Lunda country, will come under the government of Lualaba, which has not yet been installed.

The fact that the Union Miniere will now have to operate in two provinces instead of one will increase its administrative headaches— though not intolerably so if the latest plan for an inter-provincial administration for the whole of Katanga comes off—but it will almost cer- tainly shift the balance 'of power in favour of the Central Government. This will be more marked again when the Central Govern- ment's rights as the principal shareholder in the Union Miniere receive recognition as part of the general settlement of the economic issues between Belgium and the Congo that were still outstanding when the deadline of Independence Day was passed. These negotiations were re- launched during Adoula's official visit to Brussels earlier this year and have just been given new momentum by Belgium's agreement to take over half of the huge Congolese National Debt, most of it owed to Beigian bondholders, which was run up during the last decade of colonial rule. During the past three years the Congolese have ignored this obligation, with the result that the whole burden has had to be carried by the Belgian Government as guarantors. The 'Belgian Congo portfolio' was retained in Brussels as security. When handed over to Leopoldville, it will establish part-public ownership of at least eighteen major companies.

President Bulundwe, who is only thirty, has not hitherto played a prominent part in Katangese politics. 'As a member of the Conakat delegation in the Central Parliament, he would naturally have been inclined to bridge over the gulf separating Elisabethville and Leopoldville. Since the UN's action last January, the Katan- gese national politicians, led by Senator Yava, have insisted on playing a more important role as against their provincial colleagues. Four of them, including Yava, are now Ministers in the Adoula Government. Their first intention was to try to reunite the original province of Katanga, now that the reason for the north- south split—Tshombe's determination to secede and take the whole province with him, by force if necessary—no longer existed. The leader of the opposition to Tshombe in Katanga, Jason Sendwe, himself normally a resident of Elisa- bethville, had only used the traditional north- south division as a means of combating secession. When it was over he stage-managed a reconcilia- tion ceremony between supporters of his Balu- bakat Party and those of Tshombe's Conakat.

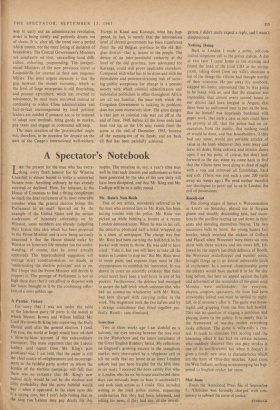

Believing that Sendwe had the north in his pocket, the leading Katangese politicians began after this rallying to the idea of a united Katanga which would be the largest province in a revised Federation, as opposed to being the smallest one in the set-up of 1960. Since then the other five original provinces had all been split. Apart from the reluctance of the Central Government to I UBANGI. 2 ULLE. 3 MOVEN CONGO. 4 HAUT CONGO. 5 KIBALI ITURI. 6 CUVETTE CENTRALE. 7 MANIEMA. 8 NORD-KIVU. 9 MAI-NDOMBE. 10 SAN KURU. 11 KONGO-CENTRALE. 12 Kwn.u. 13 UNITE KASAIENNE. 14 LOMANI. 15 KWAN00. 16 LULUABOURG. 17 Suo-KAsta. 18 NORD-KATANGA.

19 LUALABA. 20 KATANGA ORIENTAL.

see this come about, two things went wrong locally with the scheme. Tshombe, alone among the leading personalities of the secession, de- clined to be reconciled to his old enemy Sendwe, while Sendwe himself was for a time repudiated by North Katangese Ministers who wished to retain some autonomy. The balance of forces was now such that if Katanga could not be one it had to be three, and the national parliamen- tarians from Katanga, having failed to mediate between the local politicians to achieve the first alternative, finally acquiesced in the second.

Even so, the idea of a reintegrated Katanga within the Congo has not been abandoned. It is now clear that the Katangese Ministers in the Central Government switched from their—and Sendwe's—first policy of simple merger between North and South Katanga and endorsed the law creating the third province of Lualaba because they had become convinced that only on a triangular base could an 'all-Katanga' inter- provincial authority be erected. Sendwe, after his initial setback through attempting too abruptly to write off the separate province of North Katanga, appears to have reasserted his authority as political leader of the Baluba tribe.

Evariste Kimba, in many ways the ablest of the local Katangese politicians, who was left in charge of the provincial government at Elisa- bethville by Tshombe when he withdrew from the scene, was among those who acquiesced. Indeed, he acquiesced so cheerfully after a long visit to Leopoldville that it,is strongly rumoured that he is destined for high federal office. He said on his return that he did 'not want to be in the government of a small province,' that he would retire from office, but that he would carry on with current business until the arrival of the Central Government's Commissioner-General Extraordinary, who, according to what is now standard procedure, liquidates the large provinces and divides up the positions and perquisites among the small. Kimba has been as good as his word and the transition has been smooth.

Elisabethville was one possible rival to the ascendancy of Leopoldville. The second was Stanleyville, in Oriental Province, now the capital of Haut Congo--what is left of Oriental after the amputation of two new provinces.

Oriental and Katanga were the only two of the six original provinces which had any sense of identity. Their partition was primarily a political move by the centre. The others were wholly artificial and as regional units ungovern- able. Partition in their case was an indispensable preliminary to any social and economic re- covery—and this despite the staggering increase in administrative overheads involved. Almost every new province has voted to install its maxi- mum of ten Ministers, with a Provincial Presi- dent and an Assembly, all with salaries and allowances. The 'capitals' are often located in tiny villages without any of the facilities needed to conduct a modern administration. Where size- able towns exist they are often in dispute be- tween two of the new provinces, being of mixed population or situated near the common border. Under the law they must be ruled by a Special Commissioner_ of the Central Government until a referendum has been held and must not be used by provincial authorities.

While no one would describe this as an ideal way to carry out an administrative revolution, order is being slowly and patiently drawn out of chaos. It is, after all, the trend over a period which counts, not the mere listing of incidents of breakdown. The Central Government's Ministers are constantly on tour, unravelling local diffi- culties, exhorting, propounding. The inexperi- enced Ministers of the new provinces travel to Leopoldville for courses in their new responsi- bilities. The most urgent necessity is that the gap between the money economy, which at the level of large enterprises is still flourishing, and peasant agriculture, which has reverted to subsistence, be once more narrowed instead of continuing to widen. Close administration and face-to-face encouragement by local political leaders are needed if peasants are to be induced to adopt new methods, bring goods to market, pay taxes and engage in communal self-help.

The mere creation of the `provincettes' ought not, therefore, to be occasion for despair on the part of the Congo's international well-wishers. Except in Kasai and Katanga, what has hap- pened, in fact, is merely that the intermediate level of elected government has been transferred from the old Belgian province to the old Bel- gian district—that is, nearer to the people. The device of an inter-provincial authority at the level of the old province, now advocated for Katanga, could well prove applicable elsewhere. Compared with what has to be done and with the formidable and patience-straining task of secur- ing public acceptance for change in a peasant society with which colonial administrators and nationalist politicians in office throughout Africa are all too familiar, the pace with which the Congolese Government is tackling its problems does not seem excessively slow. The acute danger is that just as colonial rule was cut off at the end of June, 1960, before all the loose ends had been tied up, so the UN may vanish from the scene at the end of December, 1963, because of the running-out of its funds, and set back all that has been painfully achieved.

Previous page

Previous page