Cinema

A Kind of Hero

By ISABEL QUIGLY

Prehensibly remote by what has .come since. To People of his own generation or' even of the one straight after it there was nothing suspect about the 'cult of personality": heroes "and ,hero- W°rshiP were 'respectable enough, indeed to any people the images and emotive words they conjured--leadership. magnetism, cheering crowds, flags flying, fanatic loyalty to a person admirable and stirring. But those of us, .cv'lc) grew up since have been inoculated so uercely against such things by all that happened, in the Thirties and Forties, by what personal magnetism, private ambition on a national scale and messianic dreaming could- lead to, that our eyes are unable to look at them without sus-

Towards them, on the large scale of

world events or the small scale of minor flag- wagging (my own pet dislike' is the last. night of the Proms), we have what they used to call at school "bad spirit'—a useful . phrase involving "iticism st

questioning eyebrow-raising. It isn t

, .

, a rnatter of .finding the trappings of a man hie Lawrence or his situation unsympathetic

but even-. of questioning the Lawrence legend, take oubeingunable, right from the start, to it straight, to want it, to ratify it. It isn't a :natter Of debunking, of -slapping down what is admirable, but rather of asking what it is we av'y'lrnire, of admiring quite .other kinds of things. e may be more charitable towards Lawrence as a man than some of his cont611poraries were,. in the sense of finding him more interesting, try- ing More to see what he was up to and what the up to it; but we cannot easily swallow' me public figure: heroes of Lawrence's kind are no longer our kind of hero. •

David Lean's rather lightweight film on Law-

rence admits all this by implication, and anaging_in spite of some pretty sympathetic to andling of him and a very sympathetic actor,, s0 make. Lawrence a pretty. unsympathetic per- eon by the end–The line take with him is neither

Mplicated a nor explicit, but, middling: it makes

rig,min many hints, that audiences may seize on

interpret or not, and asks the Stbek- ques-

Cts, to which an excellent script (by Robert d)„gives some Of the answerS, qualified and

.„.° 'lied by others. 'These are not lies, they're

lu,.‘-!serns,' General Allenby says -of Lawrence's „mrPatehes from the desert, multiplying the num- _°e_of men he has by ten. Or again : 'Your name look be a household word when they have to, Which mine up in the Imperial War Museum,

avv turns out (perhaps for the complexity of

of htence"s character and the ciirious fascination his is Personality., rather than the greatness of exPloits) to be true enough. Lawrence is, of i....ns`riau_rsgm,e,ativel that hardest of all characters to treat sta tna Y—the man who, right from the

rdly sounds true, has the rather excessive snnantieism of circumstance and situation of

desert invented: add to that the marvels of rt scenery of all .sorts and in all hours and

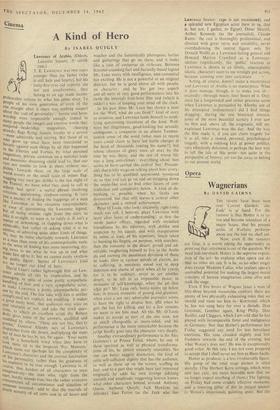

Lawrence of Arabia. (Odeon, Leicester Square; 'A' certifi- cate.)

T. E. LAWRENCE was two years younger thais my father (who is still hale and hearty), but his 41/4. - forty-five-year-old exploits are

not just anachronistic, they belong to 'an age made incom- weather and the fantastically photogenic battles and gatherings that go on there, and it looks like a case of embarras de richesses. Between fictional-sounding fact and factually-based legend Mr. Lean steers With intelligence, non-committal but exciting. He is not a powerful or an original director, but he is good above all with people, on character: and he has got two superb and all sorts of very good performances into his (with the interval).fnur-hbur 'film and (which is odder) a way of keeping your mind off the clock.

In his past films Mr. Lean has shown a taste for the 'Well, what do you think?' kind of story or situation, and Lawrence lends himself to modi- fying questioning 'treatment of the kind. Well- born but illegitimate, good-looking but sexually ambiguous, -a conqueror in an almost Tambur- lainish sense of the word (what man in recent years could claim to have led battle charges at the head of thousands roaring his name?), but whose .chances of glory were all over by the time he was thirty, and the rest of whose life was a long anti-climax : everything about him seems to have carried this central 'but.' Presum- ably that is v.. hy we, go on talking about him: every- thing has to be qualified, questioned, wondered at., so that you can go on and on stripping down the onion-like sOul, to find other layers of con- tradiction and complexity below. A kind of de- bunking is possible when his faults are discovered, but that still leaves •a -central other_ character, and a central achievement.

• Peter O'Toole, who looks uncannily right (only much' too tall, I believe), plays. Lawrence 'with layer 'after layer of understanding: at first the misfit junior officer,. regarded with mystified friendliness by his inferiors, with dislike and suspicion by his equals, and with exasperation hy some, at least, of his superiors; much taken to- burning his fingers,, on purpose, with matches; then the romantic in the desert, proud and ad- mirable; toughening himself to live as the Arabs do and earning the ,passiOnate devotion of those he leads; then in various- moods of elation, joy or suffering: in messianic mood and in deep dejection and shame of spirit when all he yearns for is to be ordinary, never to see - another desert, to be left in an impossible peace; in moments Of self-knowledge, when the pit (but What pit? Mr. Lean only hints) opens np below him; in brazen moments of 'posing and glamour, when even a not very admirable journalist seems to have the right to despise him; aid when he gets the lust for killing, and for a few minutes we seem to see him mad. All this Mr. O'Toole makes us 'accept as part of the one man, not so ffiiich changeable as many-sided, and his performance is the more remarkable because the script' hardly goes into the character very deeply.

Another extraordinary performance is Sir Alec Guinness's as Prince Feisal, whom, by one of those spiritual as well as physical transforma- tions of. his, he almcist sinisterly resembles. No one can better suggest distinction, the kind of calm self-seficient dignity that has the audience, as well as those up on the screen, scuffing its feet; and to a part that might have just remained enigmatic he adds his own strange sidelong warmth and amplitude, suggesting heaven knows what other characters behind, around. Anthony Quinn, Anthony Quayle, Jack Hawkins (as Allenby), Jose Ferrer (as the Turk who has

Lawrence beaten: rape is not mentioned). and a splendid new Egyptian actor (new to us, that is, but not, I gather, to Egypt), Omar Sharrif, Arthur Kennedy (as the journalist), Claude Rains: the cast is thoroughly professional, and directed with great verve and suitability, never overshadowing the central figure; only Sir Donald Wolfit as a Lawrence-hating general and Howard Marion Crawford as a Lawrence- idoliser (significantly, the 'public' reaction to Lawrence is shown in an idiotic, unacceptably idiotic, character) seem to me wrongly put across, because crossing over into caricature.

Acting, of course, doesn't make a masterpiece and Lawrence of Arabia is no masterpiece. What it does manage, though, is to make you sit- excitedly—through nearly four hours of it. Only once (in a longwinded and rather precious scene when Lawrence is persuaded by Allenby out of his attempted 'ordinariness') did I find things dragging : during the rest historical interest, some of the most beautiful scenery 1 ever saw on film and, above all, the enigmatic, still un- explained Lawrence won the day. 'And the way the film made it, if you can claim tragedy for it at all, into a muted, personal, psychological tragedy, with a sidelong kick at power politics, very effectively delivered, is perhaps the best way to tell the tale at this point—not quite in the perspective of history, yet too far away to belong to our present world.

Previous page

Previous page