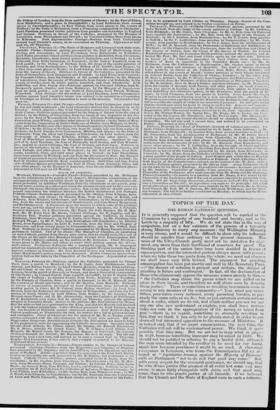

THE ROMAN CATHOLIC QUESTION.

TOPICS OF THE DAY.

Ir is generally supposed that the question will be carried in 1 he Commons by a majority of one hundred and twenty, and ill the Lords by a majority of fifty. We do not state this in the way of conjecture, but on a fair estimate of the powers of a tolerably strong Ministry io carry any measure : the Wellington Ministry is very strong, and it would be difficult to show why its influence should be smaller than ordinary on the present occasion. The noise of the Ultra-Church party must not be mistaken for argu- ment, any more than their hardihood of assertion for proof. The thinking part of the nation have long been decided in favour of emancipation, and the interested portion always move with power ; when we take these two parts from the whole, we need not observe we shall leave very little behind. The argument for granting emancipation has been put shortly and well by Mr. Secretary PEEL —" the danger of refusing is present and certain, the danger of granting is future and contingent." In fact, all the declamation of those who clamorously oppose the measure comes merely to this,- " the Catholics may abuse the power which we are called on to place in their hands, and therefore we will abuse ours by denying them justice." There is something so revolting to common sense in saying to any member of the community—" You must pay taxes, tithes, poor-rates, every national, every parochial burden, in pre- cisely the same ratio as we do ; but, as you entertain certain notions about a wafer, which we do not, and which neither you nor we nor any one else can understand or explain, you shall have neither voice nor vote in the appropriation of the money so taken from you,"—there is, we repeat, something so strangely revolting in this, that we think it has only to be plainly stated, in order to put down all but interested opposition to the measure of Ministers. It isindeed said, that if we grant emancipation, the next thing the Catholics will ask will be ecclesiastical power. We think it quite possible that they may. But we are not to deny what is proper in 1829, because something improper may be asked in 1839. We should not he justified in refusing to pay a lawful debt, although the sum were intended by the creditor to be used for our harm, much less because perchance it might be so used. A rhetorical clergyman in Longacre, who terms the Emancipation Bill an at- tempt at " legislative treason against the Majesty qf Heaven," calls on Parliament " not to do evil that good may come." But, with every respect for the reverend gentleman, we should say, that he who denies justice (the greatest of all evils) lest some evil may ensue, is more fairly chargeable with doing evil that good may come, than he who grants justice at all hazards. If we believed that the Church and the State of England were in such a tottering condition that they could not afford to be honest to a pressing—call it an impudent claimant—without danger of bankruptcy, we should entertain much less attachment to either than we at present do.

A word about Securities. The supposition that six or seven millions of people can be bound any longer than it is their interest to be bound, is so simply extravagant, that the person who se- riously entertains it must be a psychological curiosity well worthy of study—there is a bump on his head yet unclassed by SPURZ- HEIM. A declaration is talked of, and that is probably all that the Emancipation Bill will contain. The best recommendation of such a form is, that it is useless. The declaration that is imposed on Dissenters (we should add Churchmen also, for every one must make it) to what does it amount ?—that the party making it will not do what is unlawful. Why, by the common law of England, he that does wrong unwittingly is as liable to punishment as he that does so forewarned; i gnorantia legis neminem excusat.

There is a second rumoured security—namely, the abolition of the forty-shilling freeholds. This abolition can only be sought for • either because all Catholic members are supposed to be dangerous persons, or because too great a number of them may be dangerous. The former position is contradicted by the measure of emancipation itself; and if there be any thing in the latter, the plain way would be to fix the number at once ; and if more be elected than the Church can tolerate, let them cut out or settle the matter by drawing straws, or any other method that may be thought best. If forty-shilling freeholds are dangerous to the State, why tolerate them in England? It is said that in Ireland the votes are influ- enced by the priests, and that the priests have broken the tie that connected the landlord with the tenant, and out of this rupture heaven knows what calamities are to spring. We confess we have an eye of suspicion for the tie in question. We hear much of mutual benefits, but the only mutuality we have ever beheld, in these cases, is that the poor man is bound and the rich man holds the string. If we were to choose between two motives—the fear of ejection from a turf cottage and three or four acres of bog by the landlord, and the fear of incarceration in purgatory by the priest—we should cer- tainly prefer the latter as the more elevated. Superstition is not the best possible prempter, but it is purer than bribery. The forty-shilling freeholds of Ireland are much misapprehended. It has been supposed that they are different in their essence from those of England : this is incorrect, although it is true that two circumstances have tended to increase them in the former country— namely, the almost universal custom in Ireland of leases for lives, and the non-existence of copyhold. In England, leases are very sel- dom given for lives, and copyhold tenures are numerous ; yet, even here, at every election, hundreds and thousands of freeholders are made. Would any on that account, say that the present freeholds of England ought to be abolished? In Ireland, so far from there being any greater facilities of creating freeholds than in England, there are less ; for there the freeholder must be registered for a twelvemonth before he .can vote, Whereas here he may vote the day he is enrolled. Again, the complaint of the Irish landholder, of the freeholders, he has created, is extremely contemptible, when the motives to their creation are considered. It was not to increase his political power, and-thus to add to the influence of his party or his principles, that lie made freeholders by the score, but to swell the contents of his purse—to make dirty gain of the poor people's votes by the pre- sentments which they entitled him to ask; and the real cause of his present complaints is not, as he would insinuate, the diminished power of the Protestant Church of Ireland, or the danger of the constitution, but the diminished value of his estate and the danger threatened to his wine-cellar.

The Catholics, we believe, are not against the abolition. They feel assured, that in a year or two the forty-shilling freeholders would be precisely where they were before the Waterford election : they are assured that but for personal reasons of aversion to the l3eaeseoan family, that fight could never have been fought ; and that but for personal reasons of attachment to O'CONNELL, the Clare light could never have been fought ; and it is matter of strong doubt if either could be fought apin. There is a third security talked of—we mean the pensioning of the priests and bishops. This, we hope most sincerely, will be opposed, and opposed successfully. The plan is neither more nor less than to impose a tax on the whole community for the relief of the purses of his Majesty's Roman Catholic subjects. We pay tithes of our substance to the Church established by law, and we object not to that ; such of us as are Dissenters pay our own clergymen, and that too is all very proper ; but flesh and blood will not tolerate an attempt to saddle us with the payment of a third set of holy men. We conclude, then, that the Catholics, if emancipated at all, ought to be emancipated freely and fully. Se- curity can only be asked on the supposition that it is their interest to injure the Protestant party, or that they intend to do so. In either case, the only security a man of common sense would pro- pose, would be denial of power. W do not think it is their in- terest, nor, by consequence, do we think it is their intention, to use the freedom they claim to the injury of the rest of the state.

Previous page

Previous page