Reducing life to jokes

Anita Brookner

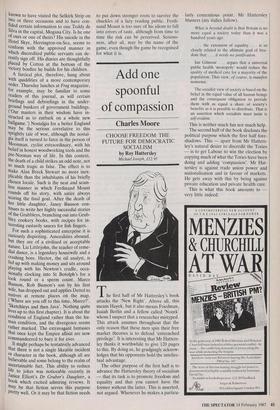

THE SELKIRK STRIP by Ferdinand Mount

Hamish Hamilton, £9.95

The Selkirk Strip is a piece of unman- ageable territory 'between the jungle and the mountains'. Originally annexed for the British Empire by the eponymous Selkirk and forgotten ever since, it swims back into public prominence when invaded by men from over the border. A fighting force of two battalions is mustered and sent off in Vulcans; shortly afterwards a shadowy victory is announced and bonfires are lit all over the country. Parallels with recent events will not be difficult to trace.

Into this framework of action — even more farcical in fiction than it was in fact— is inserted a fable of everyday North London folk. Muswell Hill, I take it, is the habitat of Nell and Gus, Liz and Hector, Janey and Rob. Their terrible dinner par- ties, at which someone invariably vomits, their activities as civil servant, oil analyst, teacher of remedial dance to retarded children, and collator of 15th-century demographic statistics, even their myste- rious acceptability as members of some bewildering contemporary intelligentsia, may be recognisable to those similarly placed. But Ferdinand Mount is a wily as well as an elegant writer and he undercuts his effects most stylishly, making all his characters incredible as well as infinitely plausible. The spirit of Evelyn Waugh hovers over this story of retreat from all recognisable standards into a kind of limbo of muddled effectiveness.

The hero, if that is not too tactless a word to introduce into this parade of duds, is Alan Breck Stewart, the bony and deviant cousin of Gus Cotton's wife, Nell. Swinging in for breakfast one morning (he was invited for tea), he stays on indefinite- ly, although he changes houses from time to time in order to impregnate Janey's au pair, Th6rese, or have an affair with Liz's husband, Hector. Everywhere he takes his files, his notebooks, and a battered civil service briefcase, raising some kind of suspicion that he may have had a disting- uished career acting in the public interest. Certainly he has attached himself to many government agencies and was briefly in Mountbatten's think tank during the war, but he is chiefly known for his inventive- ness. There was, for instance, that brilliant scheme for infiltrating Nazi Germany ►n 1939: dressed as golfers, the British would fraternise easily with the local population and thus be able to ascertain that 'only 35 per cent' of Germans favoured the exter- mination of the Jews. Gus Cotton, the real civil servant, finds his wife's cousin a bit of a trial, but is uneasily aware of that briefcase.

Unfortunately, Alan Breck Stewart is known to have visited the Selkirk Strip on two or three occasions and to have con- fided certain information to one Teddy de Silva in the capital, Mogana City. Is he one of ours or one of theirs? His suicide in the Hotel Skye, Herrington-on-Sea, seems to conform with the approved manner in which discredited public servants can de- cently sign off. His diaries are thoughtfully placed by Cotton at the bottom of the victory bonfire he builds for his children.

A farcical plot, therefore, hung about with quiddities of a more contemporary order. Thursday lunches at Frag magazine, for example, may be familiar to some readers of this journal, as will certain briefings and debriefings in the under- ground bunkers of government buildings. (`Our masters in their wisdom have in- structed us to embark on a whole new ballgame.') Nostalgia for a better England may be the serious correlative to this sprightly tale of woe, although the nostal- gia itself is turned to farce in the person of Moonman, cyclist extraordinary, with his belief in honest woodworking tools and the pre-Norman way of life. In this context, the death of a child strikes an odd note, not so much tragic as false. The effect is to make Alan Breck Stewart no more inex- plicable than the inhabitants of his briefly chosen locale. Such is the neat and seam- less manner in which Ferdinand Mount rounds off his story, with satire always scoring the final goal. After the death of her little daughter, Janey Bunson con- tinues to write her highly successful stories of the Grubbleys, branching out into Grub- bley cookery books, with recipes for in- teresting custardy sauces for fish fingers. i For such a sophisticated enterprise it is curiously dispiriting. Amoralities abound, but they are of a civilised or acceptable nature. Liz Littlejohn, the teacher of reme- dial dance, is a legendary housewife and a crashing bore. Hector, the oil analyst, is fed up with making money and sits around playing with his Newton's cradle, occa- sionally clocking into St Botolph's for a look round or a sperm count. Marco Bunson, Rob Bunson's son by his first Wife, has dropped out and applies Dettol to natives at remote places on the map, (`Where are you off to this time, Marco?'. S. ketchleys and then Java'. Nothing quite lives up to this first chapter). It is about the condition of England rather than the hu- man condition, and the divergence seems rather marked. The extravagant fantasies that once kept the Empire afloat are now Commandeered to bury it for ever. It might perhaps be tentatively advanced that there is not a single likeable incident or character in the book, although all are believable and some belong to the realm of ascertainable fact. This ability to reduce life to jokes was noticeable recently in Janice Elliott's Dr Gruber's Daughter, a book which excited admiring reviews. It may be that fiction serves this purpose pretty well. Or it may be that fiction needs to put down stronger roots to survive the chuckles of a lazy reading public. Ferdi- nand Mount is too sure of his idiom to fall into errors of taste, although from time to time the risk can be perceived. Serious- ness, after all, may be the name of the game, even though the game be recognised for what it is.

Previous page

Previous page