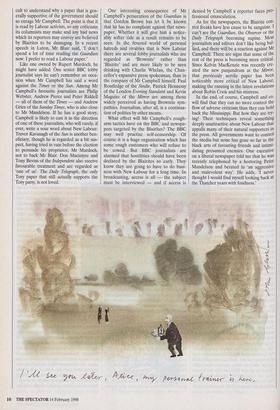

CONTROL FREAK OUT OF CONTROL

Stephen Glover on why the government's chief spokesman

spells long-term trouble for Mr Blair because other media

will prove harder to bully than the BBC IT IS difficult to exaggerate the spine- chilling effect which two attacks by Alastair Campbell and Tim Allan have had on jour- nalists at the BBC. 'It undermines self-con- fidence ,, says one senior BBC journalist. Reporters are frightened of an official complaint.' Another BBC executive says, , We are obviously vulnerable.' He means that a public service broadcaster can hardly Ignore the feelings of a political cadre that may be in power for ten or more years Washington a press conference in washington last week. Mr Sergeant had politely asked Whether Mr Blair was worried that he would be questioned about Monica Lewinsky. Mr Campbell exploded, as he so Often does. He accused the BBC of being a 'downmarket, dumbed down, over-staffed, over-bureaucratic, ridiculous organisation'. This was a little rich coming from a man who only three years ago was an assistant editor on the now defunct Today newspaper. On Friday, two days after the blameless Mr Sergeant had been ritually humiliated, Mr Allan, who is Mr Campbell's right-hand man, attacked the BBC World at One programme's cover- age of a speech by the Labour MP Brian Sedgemore. This eccentric left-winger had criticised Tony Blair for being 'above God' and described Labour's female MPs as Stepford wives'. World at One, which is broadcast on Radio Four, devoted 13 min- utes of its 40-minute programme to Mr Sedgemore's speech. In the opinion of a Labour party official, this demonstrated the BBC's 'complete loss of perspective and their increasingly trivial agenda which we have come to expect'. He did not single out World at One but broad- ened his criticisms to include the entire BBC in language reminiscent of Mr Camp- bell's. In fact neither BBC lunchtime televi- sion news nor the BBC six o'clock news that evening made any reference to Mr Sedge- more's speech. But the World at One's news priorities drew Downing Street's fire on the entire Corporation. Lady Thatcher did not work up a head of steam against the BBC until the mid-Eighties, and even then it was Norman Tebbit who blew up. But now, after nine months, this government charac- terises the BBC in more extreme terms than were ever employed by the Tories.

Alastair Campbell is a powerful man probably more powerful than his fellow spin doctor, Peter Mandelson. Before fetching up on Today he was a Labour propagandist on Robert Maxwell's Mirror, where he appears to have served his master with the same loyalty he shows for Tony Blair. His ascendancy has been almost unbelievably rapid — as though he had been transferred overnight from overseeing a small Siberian salt mine to a senior position in the Polit- buro. Other than Mr Blair and Gordon Brown, it is difficult to think of anyone in the government who carries more weight. No one who has dealt with Mr Campbell could doubt his abilities. But he is a bully. He bullies those who are critical of the Blairite 'project'. These tendencies doubt- less reflect his own character. But they also reveal something deeper about Blairism: its ultra-sensitivity and intolerance of criticism, and its desire to silence discordant voices.

Independent-minded lobby journalists say that Campbell still behaves as though an elec- tion is on. Along with Peter Mandelson, who works no less assiduously behind the scenes, Campbell honed to perfection the instant rebuttal and the immediate complaint. Then the BBC was generally anxious to co-operate. It cer- tainly did not wish to be accused of imped- ing a Labour victory. In government the Blairite PR machine expects the same com- pliance. It also thinks it can control the flow of news as effectively as it did in opposition.

Apart from the BBC, the main object of Blairite hatred is the Guardian and, to a slightly lesser extent, its sister paper, the Observer. Michael White, the Guardian's political editor, recently described in his paper the treatment which he and his col- leagues have received at the hands of Mr Campbell. 'Alastair Campbell regularly berates the Guardian at lobby briefings,' White wrote. Some people may find it diffi- cult to understand why a paper that is gen- erally supportive of the government should so enrage Mr Campbell. The point is that it is read by Labour activists, so any criticisms its columnists may make and any bad news which its reporters may convey are believed by Blairites to be damaging. In a recent speech in Luton, Mr Blair said, 'I don't spend a lot of time reading the Guardian now. I prefer to read a Labour paper.'

Like one owned by Rupert Murdoch, he might have added. One senior BBC lobby journalist says he can't remember an occa- sion when Mr Campbell has said a word against the Times or the Sun. Among Mr Campbell's favourite journalists are Philip Webster, Andrew Pierce and Peter Riddell — all of them of the Times — and Andrew Grice of the Sunday Times, who is also close to Mr Mandelson. If he has a good story, Campbell is likely to cast it in the direction of one of these journalists, who will rarely, if ever, write a sour word about New Labour. Trevor Kavanagh of the Sun is another ben- eficiary, though he is regarded as a bit sus- pect, having tried in vain before the election to persuade his proprietor, Mr Murdoch, not to back Mr Blair. Don Macintyre and Tony Bevins of the Independent also receive favourable treatment and are regarded as `one of us'. The Daily Telegraph, the only Tory paper that still actually supports the Tory party, is not loved. One interesting consequence of Mr Campbell's persecution of the Guardian is that Gordon Brown has let it be known that he has no complaint against that news- paper. Whether it will give him a notice- ably softer ride as a result remains to be seen. In the fevered world of personal hatreds and rivalries that is New Labour there are several lobby journalists who are regarded as 'Brownite rather than `Blairite' and are more likely to be seen drinking with Charlie Whelan, the Chan- cellor's expansive press spokesman, than in the company of Mr Campbell himself. Paul Routledge of the Sindie, Patrick Hennessy of the London Evening Standard and Kevin Maguire of the Mirror are among those widely perceived as having Brownite sym- pathies. Journalism, after all, is a continua- tion of politics by other means.

What effect will Mr Campbell's rough- arm tactics have on the BBC and newspa- pers targeted by the Blairites? The BBC may well practise self-censorship. Of course it is a huge organisation which has some rough customers who will refuse to be cowed. But BBC journalists are alarmed that hostilities should have been declared by the Blairites so early. They know they are going to have to do busi- ness with New Labour for a long time. In broadcasting, access is all — the subject must be interviewed — and if access is denied by Campbell a reporter faces pro- fessional emasculation.

As for the newspapers, the Blairite con- trol freaks have less cause to be sanguine. I can't see the Guardian, the Observer or the Daily Telegraph becoming supine. Most journalists and editors don't like being bul- lied, and there will be a reaction against Mr Campbell. There are signs that some of the rest of the press is becoming more critical. Since Kelvin MacKenzie was recently cre- ated the new panjandrum at the Mirror, that previously servile paper has been noticeably more critical of New Labour, making the running in the latest revelations about Robin Cook and his mistress.

In the end, of course, Campbell and co. will find that they can no more control the flow of adverse criticism than they can hold back the Mississippi. But how they are try- ing! Their techniques reveal something deeply unattractive about New Labour that appalls many of their natural supporters in the press. All governments want to control the media but none has gone so far in the black arts of favouring friends and intimi- dating presumed enemies. One executive on a liberal newspaper told me that he was recently telephoned by a hectoring Peter Mandelson and berated in 'an aggressive and malevolent way'. He adds, never thought I would find myself looking back at the Thatcher years with fondness.'

Previous page

Previous page