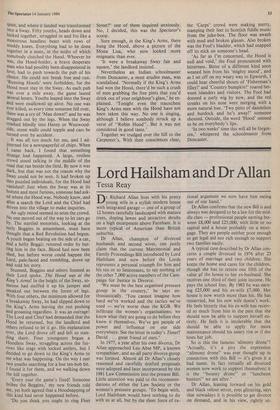

Baffling the Boggins

Roy Kerridge

'The town of Epworth in Lincolnshire is

not only the birthplace of John Wesley but the unofficial capital of the Isle of Ax- holme. Despite the efforts of the Dutchman Vermuyden, who drained the fens in the 17th century, the islanders still claim proud- ly that they are entirely surrounded by water in ditch, dyke, canal and river. From St Andrew's Church on the hill, two ruined windmills can be seen, standing sentinel over rolling treeless countryside. One of the mills, complete with black onion dome has been joined to a 'trendy' concrete house, now itself a ruin.

My destination was another part of the island, the nearby village of Haxey. There, every 6 January, on Old Christmas Day, is played a curious game known as Haxey Hood. The Hood itself resembles a large German sausage, brown and shiny and about two feet long, a thick strip of rope encased in leather. According to legend, Lady Mowbray was crossing a hill outside Haxey one day in the 13th century, when her hood blew away across the fields. Thir- teen peasants rushed after it like mad, and despite the strong wind one brought it `I suppose he should be able to recognise the signs.' back, to be rewarded with the title of Lord Boggin. The grateful lady awarded the men the land they had raced over and the men of Haxey were asked to re-enact the event every year. So far they have always done so, and the main players and organisers are still called Boggins. Learned folklorists, needless to say, have found a pagan origin in the Hood Game, and some trace it back to the fertility rites of the ancient Celts.

Whatever the truth of the matter, I was glad I had come to the Isle of Axholme. I found a comfortable room in the Red Lion overlooking Epworth's cobbled market square, with its tree and Christmas lights in bright festoons.

`Everyone will be staying away from school tomorrow with the Hood on,' the landlord's son told me.

`The Boggins come round here, singing,' his mother added. 'For a week before the game they go round the pubs in all the villages singing really old songs.'

So it was with a sense of mounting excite- ment that I hurried on to Haxey next day, scrambling along the bed of a disused railway line. Haxey villaged seemed to be built up and down a long street, with a church at one end and a pub, the King's Arms, at the other.

`No matter which pub holds the Hood, the King's Arms or the Carpenter's, the big- gest celebration is always at the King's,' the postmaster, a keen fan, told me. So to the King's Arms I went, where I found the Bog- gins in red jerseys, looking very like rugby players. Sturdy young men with short curly hair, they gave the lie to one of Orwell's prophecies, that very soon no one would say, 'I were cooming oop street' any more.

. So I took a look mysen, and there was 'ood staring me int face, laik, sort of thing, laik,' one of them remarked. This proved to be prophecy of a more inspired order, for at that moment the door flew open and in strode the Lord Boggin holding the sausage-like Hood. He was followed by the Chief Boggin and the Fool. They made an impressive entrance, for both Lord and Chief wore huntsman's jackets and boots, together with hats covered in plastic flowers and ornaments, topped by two pheasant tails sticking up in the air. Middle-aged men, they did not let their head-dresses in- terfere with their natural dignity. As staff of office, the Lord held a rod of willows bound with withy bands. The Fool's hat was of green velvet, covered in badges, and he wore white baggy trousers with red pat- ches sewn on them.

I introduced myself, and found that all three men took the Hood Game very seriously. It was by no means a frolic, for local feeling ran high, and 'King's Arms' and 'Carps' supporters were as fervent as football fans. The object of the game was to push the Hood against the opposing crowd into your pub doorway, and the win- ning pub held the Hood for a year. As the `Carps' was at Westwoodside, a mile or so out of Haxey village, there was a strong feeling of rivalry afoot. A third pub, halfway between the two, was now closed on Hood Night, as the landlady feared for her carpet and curtains. If that landlady could hear what some of the young men were saying about her, she would turn as red as a Boggin. Several older people in the village saw her point of view, and one later told me that `no one leaves cars out on Hood Night. Sometimes the lads turn them over or dance on the roofs in their great boots.'

Just now, however, all was peaceful, as the Fool had his face ceremonially made up in streaks and blotches of black and red. Then the younger Boggins lined behind the three leaders and gave us a deep rousing chorus of 'To Be a Farmer's Boy'. Many of the drinkers present worked on the land, and looked down into their glasses modest- ly. Local newspapermen crowded around Stan Borr, the Lord Boggin, oldest of the team, who had held his post for many a year. Arthur Clark, the Chief, was a shrewd, horsy Flurry Knox of a man, well suited to his huntsman's jacket. After a few more drinks, the Boggins gave us a hearty version of 'John Barleycorn': `He'll make a man into a fool And a fool into an ass!'

sang the Fool in a booming voice.

Inspired by good Sir John Barleycorn, Bt, they finished their concert with a curious ditty called 'Drink Old England Dry'. This appeared to be about the Napoleonic Wars, but had been updated to include later heroes and enemies.

`Supposing we should meet with the Germans by the way, Ten thousand to one we will show them British play!

With our swords and our cutlasses we'll fight until we die, we die, Before that they shall come and drink old England dry!

Then up spake Lord Roberts of fame and renown, He swears he'll be true to his country and his crown!

For the cannons they shall rattle and the bullets they shall fly, shall fly, Before that they shall come and drink old England dry!'

One more drink and the Boggins were away, leaping into the back of a lorry that was to take them to the Carpenter's Arms. No more was seen of them for an hour, by which time a large crowd had assembled around a flat stone outside the churchyard wall, formerly the village cross. Mothers, children and tweedy couples with dogs formed a calming influence. Having whizz- ed right around the parish, the scarlet Bog- gins could now be seen striding up the village street in a line. When they reached the stone, the Fool suddenly made a dash for it. With a roar the young men set off in pursuit and carried him back, kicking and struggling. Holding the Hood aloft in his right hand, he climbed on to the stone and made a welcoming speech, apparently unaware that a sack of straw had been tip- ped out behind him and set on fire.

`Matches? Do you want a light for a cigarette?' he asked innocently.

Flames shot up within an inch of his posterior. Named Peter Bee, the Fool was known to his friends as 'Buzzbum'. Despite his uncomfortable position, he gave a serious talk to the young men, for anybody could join in the game, and all had to know the rules.

‘NOw remember, this isn't a Running Hood, it's a Sway Hood!' he warned. 'If anyone's caught running with the Hood he'll be sent back and the Hood will be thrown again. And I'm not joking!'

'Neither's that fire,' a housewife observ- ed, as a tongue of flame few pantwards. Quickly, the Fool ended his speech with

`Oh, I don't think I could — I'm not even a co-respondent.'

the ritual words: `Hoose against hoose, Toon against toon! If thou meets a man Knock 'im doon! (But don't 'urt 'im.)'

With that the Fool jumped down before he could prove the folklorists right and become a human sacrifice. The fire was put out, the Lord took the Hood and the Fool waved a stick and bladder at the crowds. In a great mass, what appeared to be all the islanders of Axholme surged after the Boggins on to a bare windy hill outside town. This was supposed to be the spot where Lady Mowbray had lost her hood. We all clumped across the ploughed hillside and gathered round the Lord, who planted his willow staff in the furrows.

`The farmer always ploughs this field so you don't get hurt when you fall down on the soft earth,' a Hood-follower told me. However, this did not explain why the field was covered in green spouting wheat. Perhaps a good trampling from a Hood Game does wonders for the crops.

A heap of false Hoods, made of sacking, were piled around the Lord's feet. Members of the crowd, usually pretty girls, were in- vited to throw these for the local boys to fight over. If a player could reach a pub doorway with his trophy he would receive a prize of 'ten bob'. The sturdy islanders would as soon say 'fifty pence' as declare that they came from 'Humberside', another taboo word. If anyone pronounced 'hoose' as 'house' he was sternly corrected, for the rhyme had to be repeated each time a Hood was thrown.

As soon as a Hood went up in the air the young men rushed towards it, knocking down anyone in their way. Rugby tackles sent the rich earth flying, and bruised young men, often dressed in baggy overalls, sat nursing their injuries ruefully. The Hood could be thrown from man to man, but the Boggins usually caught it and it was then taken back to the Lord for a rethrow. No one was allowed to tackle a Boggin, and every time a Hood was lost in this way, the loser shouted, 'Boggined!' However, a visiting youth from Scunthorpe did fell a Boggin, and received an awful ticking off from his mates.

`Why hadn't nobody told me?' he howled at the top of his voice. To my alarm, a Hood flew over my head, and I feared I would go down with the scrum. Memories of total despair and bewilderment on the school football field flooded back to my mind.

'But what is the object of all this?' I remembered asking myself, as I avoided the stampeding hordes at my first game. Those early primary school lessons in avoiding sportsmen now stood me in good stead, and I escaped the Revenge of the Hood.

After these skirmishes, the game grew serious, as the real leather Hood was held aloft by the Lord and the 'Hoose' incanta- tion was chanted for the last time. Through the darkening twilight the mighty sausage spun, and where it landed was transformed into a Sway. Fifty youths, heads down and locked together, struggled to and fro like a monstrous headless beast with rows of muddy knees. Everything had to be done together in a mass, in the midst of which somebody clutched the Hood. Whoever he was, the Hood-holder, a brave desperate man who had possibly been disappointed in love, had to push towards the pub of his choice. He could not break free and run. Running Hoods' were forbidden, for the Hood must stay in the Sway. As each pub was over a mile away, the game lasted several hours. Youths leaped into the Sway and were swallowed up alive. No one was ever killed, as every time someone fell over, there was a cry of 'Man down!' and he was dragged out by the legs. When the Sway crashed blindly into Haxey or Westwood- side, stone walls could topple and cars be turned over by accident.

It was all too much for me, and I ad- journed for a newspaperful of chips. When I came back, I found that something strange had happened. A large, restless crowd stood talking in the middle of the road that ran beside the field. By now it was dark, but that was not the reason why the Sway could not be seen. It had broken up into puzzled individuals, for the Hood had vanished! Just when the Sway was at its hottest and most furious, someone had ask- ed where the Hood was. Nobody knew, and after a search the Lord and the Chief had driven into the village to make inquiries.

An ugly mood seemed to seize the crowd. No one moved out of the way to let cars go by. The startled motorists, looking at the surly Boggins in amazement, must have thought that a Red Revolution had begun.

A youth began beating on the side of a car, and a hefty Boggiz restored order by but- ting him in the face. Blood had now been shed, but before worse could happen the, Lord, pale-faced and trembling, drove up and told his story.

Stunned, Boggins and others listened as their Lord spoke. The Hood was at the King's Arms! In the height of the Sway, so- meone had stuffed it up his jumper and sneaked out between the forest of legs. With four others, the minimum allowed for a breakaway Sway, he had slipped down to the King's Arms leaving the rest pushing and groaning regardless. It was an outrage!

The Lord and Chief had demanded that the Hood be returned, but the landlord and others refused to let it go. His explanation over, the Lord drove off and left us stan- ding there. Four youngsters began a Hoodless Sway, struggling across the fur- rows like stags with locked antlers, but I decided to go down to the King's Arms to see what was happening. On the way I met two youths searching fora lost ten-bob bit.

I found it for them, and we walking down the hill together,

`Every year the game's fixed! Someone bribes the Boggins,' my new friends told me, yet both agreed that a Hoodnapping of this kind had never happened before.

'Do you think you ought to ring Fleet

Street?' one of them inquired anxiously. No, I decided, this was the Spectator's scoop.

Sure enough, in the King's Arms, there hung the Hood, above a picture of the Mona Lisa, who now looked more enigmatic than ever.

'It were a breakaway Sway fair and square,' the landlord insisted.

Nevertheless an Indian schoolmaster from Doncaster, a most erudite man, was scandalised. 'Normally if the King's Arms had won the Hood, there'd be such a crush of men grabbing the free pints that you'd drink out of your neighbour's glass,' he ex- plained. `Tonight even the staunchest King's Arms men with the Hood have not been taken this way. No one is singing, although I believe sombody struck up a verse of "Robin Hood". But it was not considered in good taste.'

Together we trudged over the hill to the Carpenter's. With their consciences clear, the 'Carps' crowd were making merry, stamping their feet to Scottish fiddle music from the juke-box. The floor was awash with mud and broken glasses. Also broken was the Fool's bladder, which had snapped off its stick on someone's head.

`As far as I'm concerned, the Hood is null and void,' the Fool pronounced with bitterness. Bitter of a different kind soon weaned him from his 'mighty mood', and as I set off on my weary way to Epworth, I could hear cheerful shouts of 'Fisherman's filley!' and 'Country bumpkin!' roared bet- ween islanders and visitors. The Fool had donned a curly wig by now, and the red streaks on his nose were merging with a more natural hue. 'Two pints of dandelion and burdock and he's away!' someone shouted. Outside, the word 'Hood' seemed to be on everybody's lips.

`In two weeks' time this will all be forgot- ten,' whispered the schoolmaster from Doncaster.

Previous page

Previous page