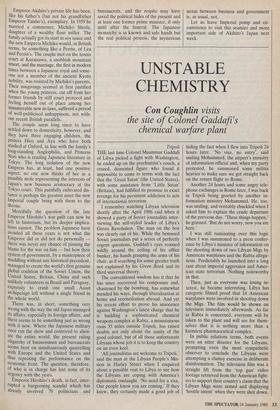

THE EMPEROR'S MORTAL REMAINS

Emperor Hirohito finally proved he was legacy he has left to his son

Tokyo ALL flesh, we know, is grass. Just the same, right up to the end it seemed possible that the frail little man who had seen his country through ruin and rebirth, firestorm and earthquake, who had stoical- ly presided over one of the more abject defeats and astonishing comebacks in all history might suddenly be back among us, peering myopically down his microscope and murmuring his all-purpose comment for every turn of an eventful life, `Ah so!'

The game old Emperor did not, it turns out, stand much of a chance from the onset of his last illness. After a lengthy abdomin- al operation late in 1987 the Imperial Household Agency, a stuffy bureaucratic hangover from the days of Hirohito's former divinity, solemnly announced that the Emperor did not have cancer, although the Tokyo University pathologist who con- ducted the post-operative biopsy not only found malignant cells, but ironically died of the same disease three months later. To the end, the palace officials around Hirohi- to insisted that he was suffering from `chronic pancreatitis', whatever that might be, all the while issuing meaningless daily bulletins on the Imperial pulse, blood pressure and temperature.

The point of this childish deceit, they now tell us, was to protect the Emperor himself from distress at the knowledge that his time was running out. That an accom- plished biologist and Fellow of the Royal Society (under Section 8 which honours `foreign dignitaries who have made a dis- tinguished contribution to science') might himself have made a shrewd guess as to Why he was receiving massive daily blood transfusions seems not to have occurred to these fossils, who unfortunately now have the new Emperor in their charge, at least until mortality taps them on the shoulder.

The 1,000-year-old notion that the Japanese Emperor is not a divine ruler, or even a responsible adult but a living doll to be petted, pampered and manipulated to suit bureaucratic reasons of state dies hard among the Tokyo court officials, a point not missed by the Japanese press, who now say that of course they knew the real situation and even whispered it to foreign colleagues who were unable to get con- firmation from any Japanese source. The businessman's paper Yomiuri, for instance, calling Hirohito's last days a 'sad decep- tion', claims that it had the cancer story all along, while offering its readers no ex- planation as to why we were kept in the dark. The complicity of Japanese officials and the media in treating not just the Emperor but the Japanese people and by extension the rest of us like children, not grown-up enough to bear harsh truths, is only one of the relics of the autocratic shoguns to which the new reign might well address itself.

The same might be said about the touchy subject of the late Emperor's war guilt, which only now that he has gone to his ancestors is being broached, timidly it is true, by Japanese officialdom. 'He re- solutely brought to an end the deplorable war that had broken out in spite of his wishes, out of a determination to prevent further suffering of the people, regardless of the consequences to his own person,' said the Prime Minister, Naboru Takeshi- ta, in the panegyric he delivered on the day of Hirohito's demise. That the Emperor did finally stop the war is true, and very much to his credit, but at most only a week or two before organised Japanese resist- ance would have collapsed anyway for lack of food and fuel. The really important result of Japan's timely surrender was that the country was not, like Germany, parti- tioned between the United States and the Soviet Union, whose armies were at that moment crashing through the last Japanese defences in Manchuria. The consequences of a Marxist half-Japan would have been, to say the least, interesting.

But the Emperor was not, as his last prime minister seems to be suggesting, exactly a member of the Japanese resist- ance either, at least not in the heady days of Pearl Harbor and Singapore. No one plausibly suggests that Hirohito either planned or pushed Japan's bid to build a European-style empire on mainland Asia, which began before he was born with the pushover defeat of China in 1890, and began to gather speed with the astonishing defeat of Russia in the war of 1904-5, when the future Emperor was three — a Japanese victory welcomed by every right- thinking progressive liberal of the world, headed by the British who supplied the warships, the military advice and every other encouragement we could think of.

However, when the choice came be- tween getting out of China altogether, as the Americans demanded-late in 1941, or seizing the oil to continue empire-building after first eliminating American and British naval power in the Pacific, Hirohito with many misgivings brushed and sealed the declaration of war himself. The American ultimatum was, Hirohito thought, 'exces- sive', as his Grand Chamberlain Sukemasa Irie told me years later in a frank discus- sion of his boss's wartime role. Japan, in other words, had no honourable course but to fight. Had Hirohito refused to sign, as the then current Japanese constitution required him to do, the Army had many precedents for deposing him in favour of his brother who was actually a serving officer; but there is no evidence that Hirohito was unwilling, only uneasy about the consequences.

Hirohito took no known part in the running of the war, not perhaps surprising- ly as he had neither military education nor aptitude. The Emperor who found the courage to say that enough was enough in 1945 was a not much older, but very much wiser Hirohito than the 40-year strip- ling (by Japanese standards) who had been assured by bearded, bemedalled and up to that point successful generals and admirals that Japan had a fighting chance of repeating the victory over mighty Russia against feebler enemies, money-grubbing America and decadent Britain. Like so many crass historical misjudgments, Japan's wider war seemed a good, or at least the best available, idea at the time. To expect Hirohito to have resisted the entire Japanese establishment, even if he was minded to, abandon Japan's conquests and run the country single-handed was to ask a cloistered, unworldly and still re- latively young man to have behaved, well, like a god.

After the surrender, many people thought that the Emperor should and would hang for his signature on the dec- laration of war and the subsequent free use made of his name in waging it — every kamikaze pilot before his take-off, for instance, sipped a cup of sake supposedly personally presented by the Emperor. Ev- ery soldier, sailor and prison camp guard swore an oath of loyalty to the Imperial personage. The same thought seems to have occurred to Hirohito himself when he called uninvited on General Douglas MacArthur a month after the surrender to take personal responsibility for everything that had been done in his name. 'Kill me if you like, but do not let my people starve,' MacArthur later reported Hirohito as pleading. Japanese tradition in fact re- quires the top man, not to mention the top god, to take responsibility when things go wrong, even for the actions of underlings he knew nothing about.

The Macarto was, however, not only something of a snob, but shrewd enough to see that the little man who delivered this penitent but far from subservient speech both accepted the idea of American occupation, again as the best alternative in sight, and could save the American tax- payers enormous sums and perhaps Amer- ican lives as well in carrying it out. MacAr- thur himself seems to have decided, then and there, that Hirohito should not hang, or even be brought to trial, and much subsequent elbow-jogging from Canada, Australia, the American West Coast, Hol- land and, it is said, Britain failed to change his mind. (What part our own royal family, always on friendly terms with Japan's, played in this may never be known.) At any rate the decision stands, 44 years on, as one of the few taken by an American general in the Far East which has so far worked out well.

Again it was a question of alternatives. Perpetual American rule was against both AMerican tradition and the taxpayers' interest. Republics may be the most evolved form of government but few tradition-ridden, class-conscious, tea- drinking island nations are ready for them and Japan in 1945 certainly was not, and is not now. No Asian country east of Calcutta has in historic fact ever managed a success- ful republic that has not become a device for dictatorship or kleptocracy. The Weimar Republic never succeeded in ex- punging the stain of having been forced on Germany by defeat, a slur much exploited by the man with the moustache, and it seems likely that a Japanese republic im- posed by atom bombs would by now have gone the same way.

Limited or constitutional monarchies on the other hand have .a track record of stability in Asia and elsewhere, for sound psychological reasons. They separate the magical and ceremonial elements of gov- ernment from the mud-slinging, sly com- promising and inevitable failure of real policies and real politicians, and so corres- pond to the division between the optimistic child and soured quasi-adult in all of us. The statewreck of defeat is, however, no time to launch a new dynasty, and Japan had no rival claimants waiting in the wings, no Bourbons, Habsburgs or kings over the water. It was either the existing Imperial line or a workers' republic. Hirohito, whatever his past, was in MacArthur's view no more of a Red than he was.

Many people thought that the defeated Hirohito should have abdicated or been deposed in favour of his son Akihito, then 12 — that, in other words, the handover we have just seen should have taken place 44 years ago, at the end of the war. In retrospect this scheme had little to recom- mend it. There would have had to have been a regency, probably conducted by the

same officials who have been managing the news of the late Emperor's illness. Hirohi- to himself could no doubt have retired happily to a scientific job somewhere neither a Napoleon polishing his martyr's image on St Helena nor Kaiser Bill sulkily breeding dogs at Doom would have fitted his studious style — but the boy Emperor Akihito would have started off as the son of the discredited war criminal Hirohito, a shaky beginning to a regency already wide open to suspicion of manipulation by sinis- ter figures behind the palace's paper walls.

As it was, Hirohito renounced his divin- ity, a device for military rule that had become irrelevant anyway, cut up his uniforms for dusters and set to, like Japan, to start all over again. The result of more than 40 years' work in rebuilding and demilitarising his office we have seen in the peaceful way in which his son has taken over this week. Such Japanese as can even remember Hirohito as an unconvincing warrior on a white horse with a sword are already pushing 60, and time has dimmed their memories and reduced the cult of the warlord Emperor to, it seems, bar-room nostalgia.

When Hirohito's grandfather Emper- or Meiji died in 1912, for instance, General Nogi, victor over the Russians, knelt in front of the palace and slashed his stomach with a sword 'to follow his lord in death' while the blameless Madame Nogi, who was not a samurai's wife for nothing, cut her throat with a small lady's dagger. Hundreds copied their example. Hirohito's passing has been marked by a solitary old soldier of 87, who never much liked post-war Japan anyway and took the opportunity to hang himself in a barn. The much-publicised right-wing revival in Japan, in short, turns out to have been largely an affair of the Sunday colour supplements, where men posing with swords photograph a lot better than robots peacefully turning out television sets.

The extreme Left, supposedly sworn ene- mies of the Japanese monarchy, have man- aged little more by way of protest as a new Emperor assumed office. Some 50 mem- bers of the Anti-Imperialist Student's Council and the Middle Core Marxist Faction shouted anti-Emperor slogans out- side Tokyo's Meiji Shrine, where Akihito's great-grandfather is worshipped as a god, and ten were arrested for conducting an `unauthorised meeting in a public place'. On the other hand, five couples took the opportunity to be married at the same shrine on the first day of a new Emperor's reign, considered an unusually effective charm against the hazards of matrimony. And the Mayor of Nagasaki who two weeks ago complained that the then ailing Hirohito had not been held to account for his part in the second world war is still, as the new reign begins, the Mayor of Naga- saki.

The great mass of Japanese are still dazed, not really convinced that the old boy has gone. (Hirohito's nickname behind his back, 'Ten-Chan', roughly corresponds to the English expression 'old boy' and certainly has much the same affectionate ring to it.) Sixty-four years is a long time to be unobtrusively but perpetually at the centre of great events, and while negative, the Emperor's achievement of never hav- ing once said the wrong thing in all those trying times is one few of us gabbier mortals can boast. No breath of scandal ever touched Hirohito personally, and the death of a distant cousin by asphyxiation from a defective oil heater in a room rented in the company of a lady not his wife is, even for disciplined Japanese, not bad going as the sole gossipable incident in a half-century of the affairs of a large and growing Imperial family.

The office Hirohito inherited was a dangerously unstable one, as front-man, or, worse, front-god for a conspiratorial clique who ran the country according to their own ideas and who were responsible to no one, even their identities being only vaguely known to ordinary Japanese and Japan's foreign partners. When the milit- ary seized the secret levers of the system, war was inevitable and Hirohito was lucky to escape the gallows. The office he has passed to his son is one with a future, requiring neither superhuman political ability nor cunning but only goodwill, common sense and a sensitivity to the fitness of things, an office well adapted to the hereditary principle which often pro- duces people of character but rarely those of genius. Is Akihito, after his long appren- ticeship (he will be 56 next December) the man for the job?

The omens look good. Akihito, even shorter than his father, is not a charismatic or big-personality monarch, but this is exactly what Japan needs — it is the office that should command respect, until the man himself imperceptibly shows his qual- ities.

Akihito is the sort of person everyone likes, but few can say exactly why. Mrs Elizabeth Vining, the American Quaker who taught him English during the Occupation, reported that he was a well- behaved boy, but shy. This, too, is all to the good; hail-fellow-well-met is not the Japanese way, and pushy self-advertising royal family members have caused enough trouble in other parts of the world. Akihito has played tennis with the bonhomous British journalist Jurek Martin, who re- cently reported in this magazine that Aki- hito's game was sound — but then again, the distinguished foreign editor of the Financial Times is himself no Pancho Gon- zales. The then Prince Akihito once played ping-pong with the sisters of Alexander Chancellor, a former editor of this maga- zine, who recall that he was 'very nice'. This confirms that we are not dealing with a ladies' man, no King Farouk.

Emperor Akihito's private life has been, like his father's (but not his grandfather Emperor Taisho's), exemplary. In 1959 he married a commoner, Michiko Shoda, daughter of a wealthy flour miller. The family actually got its start in soy sauce and the new Empress Michiko would, in British terms, be something like a Perrin, of Lea and Perrin's. The couple met on the tennis court at Kuraizawa, a snobbish mountain resort, and the marriage, the first in modem times between a Japanese royal and some- one not a member of the ancient Kyoto nobility, was resisted by Michiko's parents. Their misgivings seemed at first justified when the young princess, cut off from her former friends by stiff court protocol and feeling herself out of place among her innumerable new in-laws, suffered a period of well-publicised unhappiness, not with- out recent British parallels.

The couple seem long since to have settled down to domesticity, however, and they have three engaging children, the princes Hiro and Aya who have both studied at Oxford, in line with the family's long-standing Anglophilia, and Princess Nori who is reading Japanese literature in Tokyo. The long isolation of the new Empress has, at least, had one positive aspect: no one now thinks of her as a possible mole representing the interests of Japan's new business aristocracy at the Tokyo court. This painfully cultivated dis- tance is perhaps the greatest asset the new Imperial couple bring with them to the throne.

Mercifully the question of the late Emperor Hirohito's war guilt can now be left to historians, but its deeper implica- tions cannot. The problem Japanese have avoided all these years is not what the Emperor did or did not do personally there was never any chance of pinning the blame for the war on him — but how their system of government, by a masterpiece of muddling without any historical precedent, managed to create the world's first genuine global coalition of the Soviet Union, the United States, Britain, China and such unlikely volunteers as Brazil and Paraguay, expressly to crush one small Asian archipelago left without a single friend in the whole world.

There was, in short, something very wrong with the way the old Japan managed its affairs, especially its foreign affairs, and there seems to be something just as wrong with it now. Where the Japanese military once ran the show and contrived to alien- ate the entire world, the present ruling oligarchy of businessmen and bureaucrats seems bent on simultaneously quarrelling with Europe and the United States and thus repeating the performance on the economic front. The question, therefore, of who is in charge has lost none of its urgency with the years. Emperor Hirohito's death, in fact, inter- rupted a burgeoning scandal which has already involved 70 politicians and bureaucrats, and the respite may have saved the political hides of the present and at least one former prime minister, if only until after the funeral. The Japanese monarchy is in known and safe hands but the real political process, the mysterious nexus between business and government is, as usual, not.

Let us leave Imperial pomp and cir- cumstance to visit this seamier and more important side of Akihito's Japan next week.

Previous page

Previous page