Bright future for the terrorists

Christopher Walker

Belfast 'It is beyond the capability of Irish terrorists to obtain a nuclear weapon of fission or fusion type, or even components of such a weapon. Nor do we expect them to establish links during the next five years with any organisation which could help them obtain such a device. Anyway, they would not stage an incident in any part of Ireland which might produce nuclear pollution. Thus we believe that the contingency planning covering nuclear incidents elsewhere in the United Kingdom will embrace the small risk from Irish terrorists.' So reads one of the few reassuring paragraphs (if that is indeed its intent) in a remarkable and disturbing 27-page document drawn up by the heads of British military intelligence under the broad heading of 'Northern Ireland: Future Terrorist Trends'. Like many other controversial sections of the report, it has not previously been made public.

Last week, the Spectator obtained a full copy of the document, which, the army insists, went astray while being sent through the ordinary English post system. Even the most cursory inspection of its contents reveals that senior and highly respected officers regard the future terrorist potential of the Provisional IRA with considerably more concern than has ever been admitted by politicians in either Britain or Northern Ireland. Furthermore, the final sentence of the report (clearly stamped with the classifi cation 'Secret') destroys previous official claims that it was already out of date last May, the month that selected extracts were first released through the Press Association by IRA sources in West Belfast. Above the clearly marked date of 2 November 1978, the document concludes unambiguously: 'we further recommend that this paper should be reviewed and updated annually to provide continuing guidance to interested departments.'

The disquieting nature of its conclusions is heightened by the fact that the authors make clear at the outset that no attempt is being made to cover the potential for future Irish terrorism on the British mainland, or even the possible resurgence of Protestant paramilitary violence in Ulster. The authors also state that the five-year period under review has been chosen purely for convenience, not because the end of 1983 represents any expected conclusion to the North ernbIrefalcatndthecrigsilos.omy, almost despairing, tone of the document is quickly demonstrated in the third paragraph of the introduction which states baldly: 'even if "peace" is restored, the motivation for politically inspired violence will remain. Arms will be readily available and there will be many who are able and willing to use them. Any peace will be superficial and brittle. A new campaign may well erupt in the years ahead.' The same depressing message is repeated at the end of a section which appears to rule out any possibility of a new British political initiative, claiming that continuing direct rule from Westminster is the only form of government which offers any 'real prospect of political calm' — although candidly admitting that it leaves the underlying problem unsolved. The report, which was cleared by both the Director General of Intelligence and the Vice-Chief of General Staff, has this summary: 'Even if the present system of government is maintained, the current muted support for the forces of law and order will remain delicately balanced and susceptible to any controversial gov ernment decision or security force action. We see no prospect in the next five years of any political change which would remove PIRA's [the Provisional IRA's] raison d'etre.'

Although the mysterious disappearance of the document (the 37th copy of a restricted batch of 50 signed-for duplicates) has already caused considerable embarrassment in government circles, this has been tempered by the fact that large chunks have not previously been made public. There was particular relief in the Northern Ireland Office that, for reasons of its own, the IRA chose not to publicise the sensitive section dealing with the government of the Irish Republic. But in the light of the recent increase in Provisional IRA violence in border areas, the relevant paragraphs have taken on a new significance, and are considered by many observers to match the private views of both Conservative and Labour Ministers, who have chosen not to make them public for obvious reasons of diplomacy. They appear in a section headed: 'External Support for Terrorism other than Violence'.

Without bothering to exercise the tact which normally camouflages criticism of an EEC partner, the document states that, 'Republican sentiment and the IRA tradition emanate from the South. Although the Fianna Fail government are resolutely opposed to the use of force, its long term aims are, as Mr Lynch himself admits, similar to those of the Provisionals. Any successor to Mr Lynch in the ruling party would probably follow at least as Republican a line of policy. Fine Gael, though traditionally less Republican, is also now committed to a roughly similar line. We have no reason to suspect that PIRA obtains active support from government sources, or that it will do so in the future, but the judiciary has often been lenient and the Gardai, although cooperating with the RUC more than in the past, is still rather less than wholehearted in its pursuit of terrorists. The headquarters of the Provisionals is in the Republic. The South also provides a safe mounting base for cross-border operations and secure training areas. PIRA's logistic support flows through the Republic where arms and ammunition are received from overseas. Improvised weapons, bombs and explosives are manufactured there. Terrorists can live there without fear of extradition for crimes committed in the North. In short, the Republic provides many of the facilities of the classic safe haven so essential to any successful terrorist movement. And, it will probably continue to do so for the foreseeable future.'

Even the bureaucratic language of the report does little to disguise the depth of anger felt in military circles about what is regarded by many senior officers as a scandalous lack of security cooperation from the authorities in the Republic. Continuing resentment is caused by the fact that the Irish army refuses to allow any form of direct communication with its British coun terpart, all communication having instead to be directed through the respective police forces on either side of the 300-mile border.

Another important section of the report which the IRA's well-oiled propaganda machine omitted to mention in its selective release of the contents was that covering the organisation's own finances. The reluctance was no doubt dictated by the unsavoury details of robbery and racketeering which the document exposes, and by its clearly stated judgment that 'incompetence and dishonesty have been hallmarks of the Provisionals' commercial undertakings'.

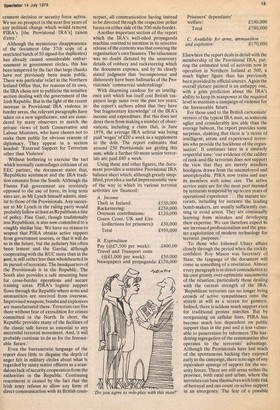

With disarming candour for an intelligence unit which has itself cost British taxpayers large sums over the past ten years, the report's authors admit that they have 'but fragmentary knowledge' of the IRA's income and expenditure. But this does not deter them from making a number of observations, including a claim that, in June 1978, the average IRA activist was being paid 'wages' of £20 a week as a supplement to the dole. The report estimates that around 250 Provisionals are getting this sum, while a further 60 more senior terrorists are paid £40 a week.

Using these and other figures, the document provides a tentative Provisional IRA balance sheet which, although greatly simplified, provides a useful impressionistic view of the way in which its various terrorist activities are financed: A. Income Theft in Ireland: £550,000 Racketeering: £250,000 Overseas contributions: £120,000 Green Cross, UK and Eire (collections for prisoners): £30,000 Total £950,000 B. Expenditure Pay (@f7,500 per week): £400,00 Travel and Transport costs (@£1,000 per week): £50,000 Newspapers and propaganda: £150,000 Prisoners' dependants' welfare: £180,000 Total £780,000 C. Available for arms, ammunition and expbosive: £170,000 Elsewhere the report deals in detail with the membership of the Provisional IRA, putting the estimated total of activists now in operation in Northern Ireland at 500, a much higher figure than has previously been provided by official sources. Again the overall picture painted is an unhappy one, with a grim prediction about the IRA's ability to keep its manpower at the required level to maintain a campaign of violence for the foreseeable future, For those used to the British cartoonists' version of the typical IRA man, as someone uglier and considerably less able than the average baboon, the report provides some surprises, claiming that there is 'a strata of intelligent, astute and experienced terrorists who provide the backbone of the organisation'. It continues later in a similarly respectful tone: 'our evidence of the calibre of rank-and-file terrorists does not support the view that they are merely mindless hooligans drawn from the unemployed and unemployable. PIRA now trains and uses its members with some care. The active service units are for the most part manned by terrorists tempered by up to ten years of operational experience . . . the mature terrorists, including for instance the leading bomb-makers, are usually sufficiently cunning to avoid arrest. They are continually learning from mistakes and developing their expertise. We can therefore expect to see increased professionalism and the greater exploitation of modern technology for terrorist purposes.'

To those who followed Ulster affairs closely through the period when the cockily confident Roy Mason was Secretary of State, the language of the document will come as something of a revelation. Almost every paragraph is in direct contradiction to his own grossly over-optimistic assessments of the situation, particularly those dealing with the current strength of the IRA. 'Republican terrorists can no longer bring crowds of active sympathisers onto the streets at will as a screen for gunmen. Indeed, there is seldom much support even for traditional protest marches. But by reorganising on cellular lines, PIRA has become much less dependent on public support than in the past and is less vulnerable to penetration by informers. The hardening segregation of the communities also operates to the terrorists' advantage. Although the Provisionals have lost much of the spontaneous backing they enjoyed early in the campaign, there is no sign of any equivalent upsurge of support for the security forces. There are still areas within the province, both rural and urban, where the terrorists can base themselves with little risk of betrayal and can count on active support in an emergency. The fear of a possible return to Protestant repression will underpin this kind of support for the Provisionals for many years to come. Loyalist action could quickly awaken it to a much more volatile level.'

Discounting paragraph 73, which states (albeit with a disturbing lack of conviction) that `we believe that Irish terrorists are unlikely to use chemical, biological or nuclear methods of attack during the next five years', there is hardly a line in the report to give comfort to the British government, prospective investors or the war-weary citizens of Northern Ireland. Throughout, the tone is uncannily reminiscent of a bullish broker's report on the bright prospects of an enterprising small company soon due for a period of modernisation.

That aspect is particularly noticeable in the last few pages, which deal at length with strategy and `targettingi. The report predicts the increased use of radio-controlled devices (like that which killed a young Scottish soldier at the weekend), the development of effective methods of cutting steel and increasing employment of long-delay electronic timers on bombs, similar to those used with such effect during the Queen's visit in 1977. 'The Provisionals have been slow to exploit the effective techniques for explosive attack that we know to be within their knowledge and competence'', the authors comment. 'We believe that, possibly aided by external contacts, their performance will improve.'

Similarly, in the vital field of weaponry, the report makes sorry reading for anyone expecting a lull in the terrorist violence which has racked Northern Ireland since 1969. 'We expect the main development in the next five years to be better sights, including possibly a laser sighting aid and night vision aids', the intelligence experts predict. 'Weapon-handling and tactics used particularly in rural attacks will probably improve. The Provisionals may attempt to step up their use of mortars . . . the RPG7 may well reappear for attacks on armoured vehicles and possibly on security force bases or prisons. Although in general we expect the Provisionals to concentrate on simple weaponry, some anti-aircraft missiles may be in their hands before the end of the period.'

Read in its entirety, the document is as depressing for the future of Northern Ireland as any which have appeared in the past ten years. Above all, it is indicative of the disturbingly wide gap between the public statements of the last government and the private advice which it was receiving from its main security and intelligence sources on the ground. The fact that the IRA deliberately chose the first week after the election to reveal that it had gained access to the report enabled Humphrey Atkins, the new Secretary of State, neatly to side-step the full gravity of its implications. But no one who has studied it can be in any doubt of the difficulties now facing the Conservative government, or of the dangers still posed by Britain's longest-running problem.

Previous page

Previous page