A BOOK OF THE MOMENT

HORACE WALPOLE

[COPYRIGHT IN TEE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY THE

New York, Times.] Reminiscences Written by Mr. Horace Walpole in 1788. Printed at Oxford at the Clarendon Press. (Humphrey

Milford. 42s. net.)

HORACE WALPOLE was one of the writers who flower both early and late. Generally in such cases the writer in the second period alters his style and makes, as it were, a new start. Horace Walpole did not do that. His Reminiscences, composed at the end of his life, show the same engaging features that characterize his early Letters. He was not a hero, nor a person capable of great sacrifices for great causes ; but he unquestionably had a liberal mind. His intelligence was never darkened by pride, or prejudice, or self-interest. He had, in fact, a Whig brain of the best kind. He lived in the great world without becoming a snob, and he lived the intel- lectual life without its particular form of vulgarity.

The waspishness of Pope, the brutality of Swift, the con- sequentialness of Addison, and the soreness, obstinacy and readiness to take offence which belonged to Johnson, had no part in his nature. He had not, I admit, a deep mind, nor a noble mind. But his heart, at any rate, was not indurated by selfishness : he often surprises one by his fairness, his kind-heartedness, his forbearance and his love of justice. An excellent example of what I mean is to be found in his frank apology and confession for his want of consideration towards Gray in their famous boys' quarrel. He says quite plainly, what was, of course, the truth, that he ought to have shown much more consideration than he did towards a man so sensitive as Gray. He realized that he ought to have remembered that he was the son of a Prime Minister and in the position of the rich and powerful man compared with Gray, that Gray was in weak health and possessed of a very "touchy" nature. All these considerations ought to have made him forbearing in the sort of quarrel which boys almost always indulge in when they are travelling companions. The only cases in which he shows bitterness and prejudice are where people attacked his father. But who will blame him for his want of judicial temper here or for his desire to strike back ? It would have been much easier for a man of Horace Walpole's temperament to have kept silence ; but he flies to arms instantly to defend his father from any attack and with the fierceness and lack of judgment of a boy in his teens.

Among Horace Walpole's works there is nothing better from the anecdotal point of view than the Reminiscences. These were written in 1788 for the amusement of Miss Mary and Miss Agnes Berry. They were first printed by Miss Mary Berry in 1798, and have long been among the chief monuments in our polite literature. Miss Berry, however, omitted a good many poignant passuges. No doubt she was obliged to do so, for there were plenty of people still living, or whose sons and daughters were living, of whom the Reminiscences contained stories of the kind which one does not want to hear about one's nearest relations. There is no great violence in these omitted stories and sayings, but they are just the things which would make people sore and angry. Now, owing to the courtesy and generosity of Mr. Pierpont Morgan, the owner of the original MS., a complete transcript has been made, and the Reminiscences are for the first time printed just as they were written. The Oxford University Press has scored a great success here and done the world-of letters a substantial benefit. So, too, has Mr. Morgan. He might have kept his treasure to -himself. By recognizing that the public have, and always must have, rights in a literary treasury, and by his willingness to impart that treasure, he has set an admirable example. No one can justly challenge the great collector's private pos- i4ession of material treasures. If collectors were not allowed such possession, half the beautiful things in the world would have been lost.

If this complete• edition of the Reminiscences stood alone it-would be a valuable hectic.. But it does not stand alone. Ito-interest rnormottaly enhanced by-Waliroles Notes-of his

Conversations (between 1759 and 1766) with the great Lady Suffolk. It was from his long talks with her that the Reminiscences were for the most part drawn, though in certain instances there are things in the Conversations which are not in the Reminiscences.

Not only is Lady Suffolk the origin of the Reminiscences ; she is also by far the most attractive of the personalities dealt with. Horace Walpole, for various family reasons, started life with a good deal of prejudice against her. In their old age, however, partly because they were both survivors from the early and middle of the century, partly because they were neighbours, and partly because they were both people who understood the great world without over-valuing it, and partly also because both had good tempers and a touch of melancholy, they found satisfaction in putting their heads together and piecing out the intimate truths of history.

In Walpole's Notes we are given a remarkable picture of this wonderful woman, for so undoubtedly she was :—

" Lady Suffolk was of a just higth, well made, extremely fair with the finest light brown hair ; was remarkably genteel, and always well drest with taste and simplicity. Those were her personal charms, for her face was regular and agreeable rather than beautiful) ; and those charms She retained with little diminution to her death at the age of 79. Her mental qualifications were by no means shining ; her eyes and countenance showed her character, which was grave and mild. Her strict love of Truth and her accurate memory were always in unison, and made her too circumstantial on trifles. She was discreet without being reserved ; and having no bad qualities, and being constant to her connections She pre-. served uncommon respect to the end of her life ; and from the propriety and decency of her behaviour was always treated as if her virtue had never been questioned ; her friends even affecting to suppose that her connection with the King had been confined to pure friendship—unfortunately his Majesty's passions were too indelicate to have been confined to Platonic love for a Woman who was deaf—sentiments he had expressed in a letter to the Queen, who however jealous of Lady Suffolk, had latterly dreaded the King's contracting a new attachment to a younger Rival, and had prevented Lady Suffolk from leaving the court as early as She had wished to. ` I don't know,' said his Majesty, why you will not let me part with an old deaf Woman of whom I am weary.' Her credit had always been extremely limited by the Queen's superior influence, and by the devotion of the Minister to her Majesty. Except a Barony, a red ribband, and a good place for her Brother, Lady Suffolk could succeed but in very subordinate recommen- dations. Her own acquisitions were to moderate, that, besides Marble Hill which cost the King ten or twelve thousand pounds, her complaisance had not been too dearly purchased. She left the court with an income so little to be envied, that, tho an Economist and not expensive, by the lapse of some annuities on lives not so prolonged as her own, She found herself straitened ; and besides Marble Hill, did not at most leave twenty thousand pounds to her family. On quitting court, She married Mr. George Berkeley, - and outlived him. No established Mistress of a Soverign ever enjoyed less of the brilliancy of the situation than Lady Suffolk. Watched and thwarted by the Queen, disclaimed by the Minister, she owed to the dignity of her own behaviour and to the contradic- tion of their enemies,. the chief respect that was paid to Her, and which but ill-compensated for the slavery of her attendance, and the mortification she endured. She was elegant ; her Lover, the reverse and most unentertaining, and void of confidence in her. His motions too were measured by etiquette and the clock. He visited her every evening at nine ; but with such dull punctuality that he frequently walked about his chamber for ten minutes with his watch in his hand, if the stated minute was not arrived."

That is a wonderful picture and I believe will be recognized as a true one by anyone who has made, as I confess to have done, a study of all that is known about Lady Suffolk, including the wonderful note of the conversation between her and Queen Caroline contained in the Report of the Historical Commission on the papers preserved at Blicking. Perhaps the best con- firmation of Walpole's prose views is to put beside it Pope's fmous poetic analysis of Lady Suffolk :—

" I know the thing that's most uncommon ;

(Envy, be silent, and attend !) I know a reasonable Woman, Handsome and witty, yet a friend :

. Not warp'd by Passion, awed by Rumour, Not grave thro' Pride, nor gay thro' Folly, An equal mixture of Good-humour, And sensible soft Melancholy.

On the other side, of course, must be put the equally famotr:, or rather infamous, character drawn of Mrs. Howard by Swift. Perhaps the best counterstroke-to this poisoned rapier thrust was given-by the victim Mrs. Howard herself. When the. character was first published in Swift's posthumous works Lady Suffolk-said of it to Walpole " in her calm, dispassionate manner "

-" rsaY-is-that,- it it Very different-from-one-that be drew of me and sent to me many years ago and which I have, written by his own hand !"

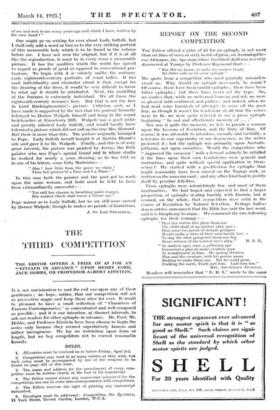

One might go on writing for ever about Lady Suffolk, but

I shall only add a word or two as to the very striking portrait of this memorable lady which is to be found in the volume before me. I have not seen the original, but if it is at all like the reproduction, it must be in every sense a memorable picture. It has the qualities which the world has agreed to regard as proofs of good as opposed to conventional por- traiture. To begin with it is entirely unlike the ordinary early eighteenth-century portraits of court ladies. It has such individuality and character about it that, except for the drawing of the dress, it would be very difficult to know to what age it should be attributed. , Next, the modelling of the features is extremely individual. We all know the eighteenth-century woman's face. But that is not the face in Lord Buckinghamshire's picture. Criticism such as I have made is supported by the fact that the portrait formerly belonged to Horace Walpole himself and hung in the round bedchamber at Strawberry Hill. Walpole was a good judge and greatly admired Lady Suffolk, and would hardly have tolerated a picture which did not call up the true Mrs. Howard. But there is more than this. The picture originally belonged to Pope. Lady Suffolk herself bought it at Martha Blount's sale and gave it to Mr. Walpole. Finally, and this is of very great interest, the picture was painted by Jervas, the Irish painter who was Pope's special friend and in whose studio he worked for nearly a year, drawing, as he has told us in one of his letters, some forty Madonnas:— " Alas ! how little from the grave we claim ! Thou but Preserv'st a Face and I a Name !"

In this case both the painter and the poet got to work upon the same woman, and both must be held to have been extraordinarily successful :-

" Yet still her charms in breathing paint engage, Her modest cheek shall warm a future age.'

Pope warms us to Lady Suffolk, but we are still more moved by Horace Walpole, though he makes no parade of laudations.

J. ST. LOE STRACHEY.

Previous page

Previous page