Dance

Barbaric

Bryan Robertson

The opening night last week of Ballet Rambert's season at Sadler's Wells (until 21 March) included the first performance of Richard Alston's new ballet The Rite of Spring, using Stravinsky's arrangement f°T, piano duet that preceded the publication 01 the orchestral score. In a special sense we were offered two new experiences: Alston's choreography and a fresh insight into the music which, if not totally radical, sortie' times seemed like the disconcerting equivalent in mnsical terms of looking at 3 well-known painting under X-ray co tions. There are musically no real surprise, s because here Stravinsky was intent 0111 upon registering the music as exactly as possible in terms of melodic line, rhYr11111' structure and pace, and allowed no purelY pianistic modulations or tonalconsiderations to obtrude between the essence of the music as he had conceived it and hi? listeners. But it is still an amazing exPeri; ence to hear those tremendous climaxes an° exultant rhythmic shifts so tightly encaPs11.; lated within the sonorities of a piano. It. vle hard for the listener to cut out instincti memories of blazing brass or crashing percussion from time to time but the piano quickly establishes its ' own concentration and authority as well as offering us a new focus on the music. This is what is important. It is how Diaghilev, Nijinsky, the designer Roerich and their companions first heard this masterpiece and Stravinsky always composed at the piano, often reiterating his need for direct physical contact with the instrument when composing and his distrust of any more abstract method of composition. This piano version of The Rite is quite beguilingly pianistic in its own right, and it does offer us in the most direct way something of the primal identity of the music, or the basic musical impulse itself, plain and severe. The piano is played with the requisite precision of attack and control of dynamics by Nicholas Carr and Christopher Swithinbank, and for a touring company with limited resources this version of a great work is a tremendous gift.

The possible hazard is that Alston's choreography, nicely matched by Peter Mumford's design a brown web-like curtain at the back and rope-like hangings at each side of the stage and lighting, and Anne Guyon's costumes, seems in its lucid solemnity and psychological texture to need at times the commensurate richness of the orchestra. Alston is the pre-eminent choreographer of the younger generation, creatively extending the language of modern dance. In The Rite, he reinforces his allegiance to the expressiveness and discipline of modern dance but, most decisively, also honours the past by defining his approach to tradition. Long stretches of his choreography, in spiral movements which animate a line of dancers until a circle is formed, or in closely packed lines and groups of dancers, disclose something of that awkward eloquence of posture and mass movement which Bronislava Nijinsky brought to such triumphant life in Les Noces, Stravinsky's other great score celebrating a primitive wedding. In this, also, some element of her brother's lost choreo graphy for The Rite was recaptured and there are moments in Alston's version when Marie Rambert's description of Nijinsky, who . . . first of all established the basic position, feet very turned in, knees slightly bent, arms held in reverse of the classical position, a primitive, prehistoric posture', seems to confront us.

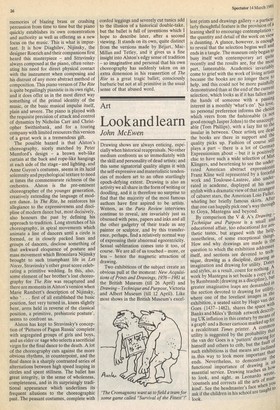

Alston has kept to Stravinsky's conception of 'Pictures of Pagan Russia' complete with segregated groups of girls and boys, and an elder or sage who selects a sacrificial virgin for the final dance to the death. A lot of the choreography cuts against the more obvious rhythms, in counterpoint, and the final dance is a sharply contrasted series of alternations between high speed leaping in circles and spent stillness. The ballet has great integrity, in the sense of wholeness, completeness, and in its surprisingly traditional appearance which underlines its frequent allusions to the choreographic past. The peasant costumes, complete with corded leggings and severely cut tunics add to the illusion of a historical double-take, but the ballet is full of inventions which I hope to describe later, after a second I viewing. It stands on its own, quite distinct from the versions made by Bejart, MacMillan and Tetley, and it gives us a fine insight into Alston's edgy sense of tradition so imaginative and personal that his own choreography has suddenly taken on an extra dimension in his reassertion of The Rite as a great tragic ballet; consciously barbaric but not at all primitive in the usual sense of that abused word.

Previous page

Previous page