`EVENTS REVERSED OUR POLICIES'

Simon Heifer interviews the

Chancellor of the Exchequer, who is, as usual, disarmingly frank

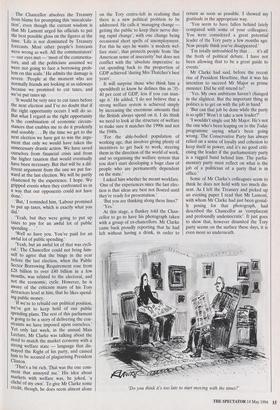

DOMINATING the grand panelled saloon that is the Chancellor of the Exchequer's office is a long mahogany dining-table. In a leather chair in the middle of that table sat Kenneth Clarke. He had just given two interviews on a subject close to his heart — football — and was radiating his cus- tomary geniality. Rubicund and relaxed, he seemed unaffected by the strains of high office.

`The Tory party's in a bit of a hole at the moment isn't it?' I asked him.

`We're having a very difficult time and the only way back from where we are is to deliver good government and achieve some policy successes,' said Mr Clarke, languidly. In this state of supreme ease he sounds even more like Mr Rory Bremner's impersonation of him than usual. Hoping to shake that ease, I invited him to deny that last week's local election debacle was a personal disaster for Mr Major.

`I think last Thursday was a protest about a government that appears to be in disarray. This disarray tends to turn on perceived battles inside the Conservative Party, and on perceived differences of opinion.' Mr Clarke spoke with remark- able detachment of 'a background of recession and of difficult policy decisions that took the Government by surprise, like the tax increases'. He was, however, upset by the activities of fellow Tory MPs — like, though he did not name him, his deputy, Mr Portillo — who he says are having 'too agitated a debate inside the party'.

I suggested to Mr Clarke, though, that the present 'debate' had been provoked by fears that single currency, or rejoining the ERM, would renew recession. He never believed, though, that fixing the currency brought about the slump.

`You know my views. I don't share the conventional wisdom. I don't think it was the ERM. I will accept that our difficulties started with Black Wednesday, because it excited that debate about whether or not ERM had been a large cause of the reces- sion, and also because events reversed our previously held policies.' Mr Clarke has refused to endorse the sentiments of Mr Portillo, who has set his face against a sin- gle currency. However, he says that 'you have to decide how you conduct economic policy without revisiting the scene of disaster.'

In that context, it might seem good poli- tics for the Tories to take the Portillo line. Mr Clarke, keen not to offend our Euro- pean partners, finds that unattractive. `Too short term, I think. For our party to get out of this hole and win back confi- dence, it's got to show it has a medium term view, that we're not just responding to political crises, but that we're trying to win longer term support . . . Things like a single currency, EMU, that kind of thing, are all very important, but it is a footnote issue right now. Why on earth we should dig ourselves into a position on it for the sake of an election in a fortnight's time . . . ?'

`You don't think the European election is important?'

`I think it's an important election, but I see no reason at all why the election should turn on our taking up a fixed position on things that aren't on the agenda at the moment, and which may not matter by the end of the century.'

It does, though, have to be discussed at the Inter-Governmental Conference in 1996, as specified in the Maastricht Treaty that Mr Clarke may or may not yet have read.

`The IGC? If I had to guess, I don't think the IGC will concern itself with EMU and monetary policy. It doesn't need to. There's the Maastricht Treaty lying there with everybody knowing the timetable's a dead duck . . . The IGC in 1996 will probably take place — it's not certain — I know we're committed to one but it doesn't nec- essarily mean it will happen in European politics. Nobody knows whether the IGC will have a serious agenda or not. It may be a big thing, it may be a non-event. It is nei- ther sensible nor democratic to say that an election campaign in Britain in June 1994 should somehow fix itself on the agenda of a conference in 1996 that may or may not be a significant event. I don't think that anybody out there thinks 1996 is going to be a great epoch-making, blueprint-draw- ing occasion.' Mr Clarke, one should remember, was among the first to pooh- pooh a referendum on the single currency, a matter on which the Government is hopelessly split.

`The debate over the ERM and the Maastricht Treaty has unsettled us. I think in an ideal world the European campaign would be a great opportunity to have a national examination of our navels as to what we think our relations with Europe should be. But it is a mistake to latch on to things that are comparative footnotes but which arouse feelings because they remind people of the ERM.'

`It doesn't seem to be a footnote to your colleagues,' I observed, a bait to which Mr Clarke was not going to rise. He loyally sought to shift the blame for the present discontents away from Mr Major. 'One dif- ficulty last Thursday was the perception of economic recovery which I have is not yet recognised by the public. There is a good recovery going on, but the ordinary man and woman in the street is feeling little or no benefit, and they certainly don't give the Government credit for it yet.'

It might be more fitting were they to give Mr George Soros the credit for it, but let that pass. One reason for the electorate's failing to see the glory of the recovery, whoever caused it, is that, according to Mr Clarke, 'in its distress, the Conservative Party has allowed itself to get drawn into arguments that distract the electorate.'

`But, Chancellor, surely it's not just a question of the party allowing itself to dis- tract the electorate, but of being allowed to do it by the leadership?'

Mr Clarke gave a benign chuckle. 'I can't remember a period when the party has done less to allow the leader to give it the sense of purpose and direction it requires. I think, particularly after the experience of 1990' — when, ironically, Mr Clarke was instrumental in Mrs Thatcher's decision to quit — 'it would be a mistake if one man had to be the scapegoat for this, and if it were thought the remedy was to start changing the leadership again. Public dis- sent is a luxury British politics does not easily afford.'

The Chancellor has not been perceived as a proper inheritor of the Tories' tax-cut- ting traditions. I asked him whether he saw a link between the low levels of location taxation imposed by Wandsworth and Westminster councils, and the fact that they were almost the only places where the Tories did well last week.

`Yee . up to a point,' he replied, becoming very Rory Bremner. He thought that in most places 'national voting intruded.'

`Like voting on the issue of tax increases?'

He gave another genial chuckle. 'That is highly relevant. It's one reason we're not yet being given credit for the recovery. I have never shied away from the indis- putable fact that we fought an election on a platform of reducing taxes, and then Nor- man Lamont and myself found we had to increase taxes. I hold the British electorate in high regard. I expect them to make it difficult for me.'

`Wasn't it wrong, too that such promises were so firmly made, only to be so quickly broken?'

`Our best mitigation for that campaign is that we seriously miscalculated the length and depth of the recession. I vehemently would deny the suggestion that anybody deceived the electorate. The campaign team seriously believed recession was over. Nobody was remotely anticipating that the recession would persist and that the PSBR would rise to levels it did.' This had, he said, left his predecessor, the unfortunate Mr Lamont, with no option but to make a `crisis reaction'. The Chancellor absolves the Treasury from blame for prompting this 'miscalcula- tion', even though the current wisdom is that Mr Lamont urged his officials to put the best possible gloss on the figures at the time. 'Life is not dominated by Treasury forecasts. Most other people's forecasts were wrong as well. All the commentators' — our eyes met — 'most of the commenta- tors, and all the politicians assumed we were not going to face a borrowing prob- lem on this scale.' He admits the damage is severe. 'People at the moment who are normally friends are looking at us sideways because we promised to cut taxes, and we've put taxes up.

`It would be very nice to cut taxes before the next election and I've no doubt that if the right opportunity occurs I will do so. But what I regard as the right opportunity Is the combination of economic circum- stances that enables me to do it prudently and sensibly ... By the time we get to the next election we have got to win the argu- ment that only we would have taken the unnecessary drastic action. We have saved ourselves from financial crisis and from the higher taxation that would eventually have been necessary. But that will be a dif- ferent argument from the one we put for- ward at the last election. We will be partly chastened by the experience, I hope. We gripped events when they confronted us in a way that our opponents could not have done.'

`But,' I reminded him, 'Labour promised to put up taxes, which is exactly what you did.'

`Yeah, but they were going to put up taxes to pay for an awful lot of public spending . . . '

`Well so have you. You've paid for an awful lot of public spending.'

`Yeah, but an awful lot of that was cycli- cal.' The Chancellor could not bring him- self to agree that the binge in the year before the last election, when the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement rose from £28 billion to over £40 billion in a few months, was related to the electoral, and not the economic, cycle. However, he is aware of the criticism many of his Tory detractors level at him, that he likes spend- ing public money.

`If we're to rebuild our political position, we've got to keep hold of our public spending plans. The rest of this parliament Is going to be a story of delivering the con- straints we have imposed upon ourselves.' Yet only last week, in the annual Mais Lecture, Mr Clarke was talking about the need to match the market economy with a strong welfare state — language that dis- mayed the Right of his party, and caused him to be accused of plagiarising President Clinton.

`That's a bit rich. That was the one com- ment that annoyed me.' His idea about markets with welfare was, he joked, 'a cliche of my own'. To give Mr Clarke some credit, though, he does seem almost alone on the Tory centre-left in realising that there is a new political problem to be addressed. He calls it 'managing change getting the public to keep their nerve dur- ing rapid change', with one change being occasional short spells of unemployment. For this he says he wants 'a modern wel- fare state', that protects people from 'the American sense of insecurity' but does not conflict with the 'absolute imperative' to cut spending back to the proportion of GDP achieved 'during Mrs Thatcher's best years'. It will surprise those who think him a spendthrift to know he defines this as '35- 40 per cent of GDP, less if you can man- age it.' He added, 'I do not believe that a strong welfare system is achieved simply by increasing the enormous amounts that the British always spend on it. I do think we need to look at the structure of welfare to make sure it matches the 1990s and not the 1940s.

`For the able-bodied population of working age, that involves giving plenty of incentives to get back to work, steering them in the direction of the world of work, and so organising the welfare system that you don't start developing a huge class of people who are permanently dependent on the state.'

I asked him whether he meant workfare. `One of the experiences since the last elec- tion is that ideas are best not floated until they're ready for presentation.'

'But you are thinking along these lines?' `Yes.'

At this stage, a flunkey told the Chan- cellor to go to have his photograph taken with a group of ex-chancellors. Mr Clarke came back proudly reporting that he had left without having a drink, in order to return as soon as possible. I showed my gratitude in the appropriate way.

`You seem to have fallen behind lately compared with some of your colleagues. You were considered a great potential leader of the Tory party a few months ago. Now people think you've disappeared.'

`I'm totally untroubled by that . . . it's all the froth of political debate. I have not been allowing that to be a great guide to events.'

Mr Clarke had said, before the recent rise of President Heseltine, that it was his intention to succeed Mr Major as prime minister. Did he still intend to?

`Yes. My own ambitions haven't changed in the slightest. But the important thing in politics is to get on with the job in hand.'

`But can that job be done while the party is so split? Won't it take a new leader?'

`I wouldn't single out Mr Major. He's not the one who's been leaping on to the Today programme saying what's been going wrong. The Conservative Party has always relied on a sense of loyalty and cohesion to keep itself in power, and it's no good criti- cising the leader if the parliamentary party is a ragged band behind him. The parlia- mentary party must reflect on what is the job of a politician of a party that is in office.'

Some of Mr Clarke's colleagues seem to think he does not hold with too much dis- sent. As I left the Treasury and picked up an evening paper I read that Mr Lamont, with whom Mr Clarke had just been genial- ly posing for that photograph, had described the Chancellor as 'complacent and profoundly undemocratic'. It just goes to show that, however disunited the Tory party seems on the surface these days, it is even more so underneath.

`Do you think it's too late to start moving with the times?'

Previous page

Previous page