ZULU BLOODLUST ON THE SCREEN

South Africans have seen a large-scale serial on the unease at the prospect of a Zulu-Boer alliance

SOME ten years ago, I voiced the sugges- tion that, should danger threaten South Africa, the Afrikaners might ally them- selves with the Zulus; I called it a 'prospect full of menace'. It now looks as though Chief Buthelezi's Inkatha movement, with or without the blessing of Pretoria, has set out to destroy the African National Con- gress in Natal. At the end of October the Daily Telegraph reported: 'The black townships of Pietermaritzburg have be- come war zones, as the two rival black groups fight for political control of the region. Unofficial re- ports say that up to 50 black corpses are pas- sing through the city's mortuaries each week . . . . There are persis- tent allegations, voiced by both rival factions, that the South African police are "standing by", as the feuding con- tinues.'

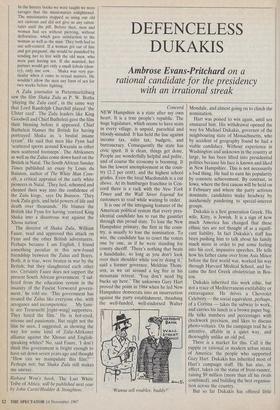

Future historians may see, more clearly than we can, how much of this new-found fighting spirit was due to the bloodthirsty television serial, Shaka Zulu, first shown in English and Zulu versions during the southern summer of 1986-87. This extraordinary and at times magnificent drama not only chronicles but exalts the first King Shaka, the black Napoleon, whose armies spread terror and death through Africa, 170 years ago. A Hollywood film company backed and pro- duced the ten-part series, but its director, William Faure, is a white South African, and of course it was shown on the state television network SABC. Black South Africans play the Zulus, and British actors play the parts of their fellow-countrymen.

The director, Faure, had the support in making the film of Chief Buthelezi, King Goodwill and Zulu historians. He and his scriptwriters have also studied the white historians, Donald R. Morris, who wrote The Washing of the Spears, and E. A. Ritter, who grew up among Zulus and based his biography, Shaka Zulu, on stories handed down from generation to generation. The film is a drama and not a documentary, so that, as Faure told me, `We had to change the story line a bit, as you would in a film about Caesar or Napoleon.'

The story begins in 1822. Lord Charles Somerset, the Governor at the Cape, was firmly opposed to annexing territory in Natal, though he favoured the establish- ment of a trading station. To that end, he gave his support to Francis Farewell and Henry Fynn, played in the film by Edward Fox and Robert Powell. A former naval lieutenant, Farewell is shown as a greedy and cynical Hooray Henry who, in his own words, would not miss a chance to serve his king and collect the ivory. Fynn, who is remembered still for a tribe of half-caste descendants, is shown as a pious and gentle Irish physician. At about this point in the film it dawned on me that Faure, the Afrikaner director, shares with the Irish an atavistic hostility to the British crown and empire.

The film Shaka Zulu does not really take off until Farewell and Fynn arrive in Natal, near what is now Durban. A Zulu regiment meets them and takes them to see the king at his kraal named KwaBulawayo, the After the meeting, the film goes back to 1786, to tell of Shaka's con- ception, birth, child- hood and rise to power. This part of the film is interesting because it portrays an Africa still untouched by the outside world; yet the drama is played by people who speak the same language and know the events from oral tradition. Here is a modern film, set in pre-history. The finest directors and the most learned scho- lars could not hope to portray life in Boadicea's England. Modern Mexicans and Peruvians have only the dimmest awareness of life under the Aztecs and Incas. The Zulus are still fresh out of Eden.

Shaka's father, Senzangakona, a junior chieftain of the then small Zulu clan, discovers the beautiful Nandi bathing in a forest stream. He asks if she will join with him in ama play endlela, literally `fun of the road', a form of supposedly safe sexual intercourse, in which the woman closes her thighs tight and the man holds back from full penetration. But on this occasion, Nandi lost control of herself, and con- ceived. The pregnancy is the more unfor- tunate because Nandi's mother belongs to a clan which is too near to the Zulus for marriage. When Nandi's family charges Senzangakona with having fathered the baby, the Zulus reply: 'Impossible. Go back home and inform them the girl is but harbouring I-Shaka' — a beetle thought to interfere with the menstrual cycle. When Nandi gave birth in 1787, she called the boy U-Shaka, and went to live in shame and disgrace as an unwanted wife of Senzangakona.

The scene showing 'the fun of the road' inspired one headline writer to call the series 'Starker Zulu'. But there is nothing prurient in the film. The Zulus take a robust and frank delight in sex, and discuss it without embarrassment. Witchcraft, not sex, is the dark and fearful influence on the Zulu mind, and it guides Shaka's destiny in the film. Witches scream and prophesy; lightning forks; and devil hyenas howl as the blood-red infant Shaka is wrenched out of Nandi's womb.

Senzangakona took Nandi and Shaka into his kraal but did not give them the love or care accorded his other wives and children. Shaka's childhood was blighted by the disgrace and unhappiness of his mother, whom he adored. When Nandi was turned out of the Zulu kraal, she went to live with her own E-Langeni people, 20 miles away. The E-Langeni scorned and rejected Nandi because she had first con- ceived while taking 'the fun of the road', and had then been expelled from her husband's kraal. The children tormented Nandi and burnt her hut. They beat and teased the friendless Shaka. According to Ritter, 'We may trace Shaka's subsequent lust for power to the fact that his little crinkled ears and the marked stumpiness of his sexual organs were ever the source of persistent ridicule.' At the age of 11, Shaka attacked and almost killed two boys who had taunted him: 'Look at his penis; it's just like a little earthworm.' The insults and humiliation nurtured in Shaka a hatred of the E-Langeni people that he would later take out on them, and on much of Africa.

As Nandi and his aunts had assured him would happen, Shaka emerged from puberty as a man with huge bones, muscles and genitals, which he delighted in putting on public display. One of the stills for the colour brochure of Shaka Zulu shows how the girl Pampata 'rubs animal fat and ochre into Shaka's body during his coronation'. In adolescence, Shaka rebelled against the elders of both his mother's and father's clan, and went to serve as herdsman and warrior with another chieftain. It was during this time of exile that Shaka in- vented the style of warfare that made him the master of south-east Africa. Shaka abandoned the light, throwing assegai and ordered the blacksmiths to forge him a short, stabbing spear called iklwa, from the noise it made when pulled out of the flesh of its victim. He made his warriors throw their sandals away and dance barefoot on thorns. He drilled his impis to fight in a crescent formation, 'the horns', with two columns attacking the foe from the flank.

Like General Montgomery, taking over the 8th Army in Egypt, Shaka expected his officers to become as fit as the men. Those who could not keep up the pace of a 60-mile route march were clubbed to death. This created a problem for William Faure. Few of the extras were tough enough to go barefoot, while some of the pot-bellied actors, cast as generals, looked as though they could not survive a route march longer than that from the taxi into a night-club in Soweto. But Henry Cele lopes at the head of an impi, as to the manner born.

When Shaka hears of his father's death, he says: 'My conception was a moment of pleasure for him but the beginning of a life-long struggle for me. If I have tears to, shed they are for myself.' He goes to the Zulu kraal where the elders have tried to instal as the new king a cowardly half-wit. The wretch grovels and kneels to Shaka, who smiles, and puts him out of his misery with a casual jab of his spear.

When Shaka became their king, in 1816, the Zulus were one of dozens of clans of the Nguni people. These clans co-existed in spite of arguments over land, cattle and women. Before Shaka, the wars were really just stylised tournaments, in which the two sides hurled their spears, at a safe distance, and traded insults rather than blows. The women and elders cheered the young braves from the sideline. When Shaka went into battle, using his new short spears and his horn formation, he ordered the Zulus to slaughter the enemy to the last man, and often the women and children as well. 'Strike an enemy once and for all. Let him cease to exist as a tribe or he will live to fly at your throat again.' Within five years he was master of what is now Zululand, taking all those who surrendered into his Zulu army. From 1822 onward, Shaka dispatched his impis abroad. They moved south across Natal, driving before them a host of terrified peoples — the Sothos into their mountain fastness, the Xhosas into the British Cape Colony. His impis struck north and west into Swaziland and the present Transvaal. One of Shaka's commanders, Mzilikazi, failed in battle against the Swazis, and, fearing execution if he returned home, took his army in flight to the north, not feeling safe from Shaka's revenge until he had reached the present Zimbabwe. He called his kraal after Sha- ka's Bulawayo, which is how it remains today as capital of the Matabeles. The South African poet Roy Campbell com- pared Mzilikazi's defection to Tito's quar- rel with Stalin in 1948.

In their panic dread of the Zulus, the other clans fought with each other for food and shelter. According to the historian Morris, two million people were killed in the few years that it took Shaka to build his empire. This was before either the British or Boers had come to the region, except as solitary traders. So much for the theory advanced on British television by pundits like Basil Davidson and Professor Ali Mazrui that Africa was a peaceful land before the whites arrived.

Those who remained under Shaka's sovereignty lived or died at his whim. One of his first acts as king was to conquer his mother's clan, the E-Langeni. He remem- bered all those men who as boys had tormented him; he had them impaled on stakes, to die in agony, pecked at by vultures. From this point in the film, impaling sticks are part of the set at KwaBulawayo. Shaka was always accom- panied by his executioners, ready to club a man to death, or break his neck with a twist of the skull. He would kill a man for sneezing, or making him laugh when he was not in the mood. He killed whole regiments for the slightest failure in battle. Women who conceived, like Nandi, after the `fun of the road', were killed along with the man responsible.

One striking episode moves from the kraal with its rotting corpses into the Great House, where Shaka and Fynn are talking at night. Shaka takes up the Bible and studies a plate of Christ on the Cross. 'Who was he?' A king.' Was Christ greater than George? His death, hanging from a tree, near weeping old women, is not worthy of a king. How did he come to die?' He was betrayed by those he loved the most.' To which Shaka, thinking of the attempted murder, says, 'Yes, it is a mistake to love, especially for a king.' He greets with a sardonic smile Fynn's protestation that `with Christ in your heart, you are stronger than all the regiments on earth'.

Shaka rejects the love of Christ, and also the love of women. 'A man who builds a road to heaven must travel alone,' he says in the film, rejecting the girl who had rubbed in ochre and animal fat. The film includes one sexual encounter but Shaka renounces the baby. Shaka kept a harem of more than a thousand girls, but according to Ritter, 'Although Shaka imparted full satisfaction to all his partners by means of Nguni "love-play" he was only able to deflower a reasonable number; according to Langazana they numbered "less than the fingers of two hands".' The leading mod- ern historian of the Zulus, Donald R. Morris, says bluntly: 'He was unquestion- ably a latent homosexual, and despite the fact that his genitals had more than made up for their previous dilatoriness . . . he was probably impotent.'

The only human being that Shaka really loved was his mother, Nandi. Her death in 1827 drove Shaka into despair and mad- ness. According to Fynn, who was one of the frightened witnesses, Shaka indulged in a day and a night of lamentation, and ordered several men to be killed on the spot:

No further orders were needed; but as if bent on convincing their chief of their extreme grief, the multitude commenced a general massacre. Many of them received the blow of death while inflicitng it on others, each taking the opportunity of revenging his injuries, real or imaginary. Those who could no more force tears from their eyes — those who were found near the river panting for water — were beaten to death by others who were mad with excitement. Towards the afternoon I calculated that not fewer than seven thousand people had fallen in this frightful, indiscriminate massacre.

After three days, Nandi was buried with ten of her handmaidens, their arms and legs were broken, then they were thrown still alive into the grave. Shaka gave orders that no crops were to be planted during the next year, and no milk drunk from the cows. All women found pregnant during the next year were to be killed, along with their husbands. He sent out regiments to the most distant kraals to enforce these orders and kill all those who had not sufficiently grieved for Nandi. He ordered the killing of milch-cows so that their calves should know the sorrow of losing a mother.

A year after Nandi's death, Shaka be- came obsessed with smelling out sorcerers and with diabolical science. He rounded up about 300 women and asked each one if she kept a cat, which in Zululand as in Europe was thought to be a familiar of witches. Whatever the woman answered, Shaka killed her. He cut open a hundred pregnant women to study the growing foetus. These incidents do not come in the television film, though there are others almost as blood-curdling.

The plot to destroy Shaka was hatched by his aunt Mkabayi, who may have • thought he had poisoned his mother Nan- di. She enlisted the help of two of Shaka's half-brothers, and of the chamberlain at the Great House. The conspirators closed on him from behind and pierced him with spears. Zulu legend says that the vultures did not feed on the massive corpse. His aunt Mkabayi then ordered the burning of Shaka's kraal at KwaBulawayo, the Place of Killing. As the credits come on the screen at the end of the last instalment of Shaka Zulu, we see the smoke rise in a great pillar, blown sideways over the hill- side, and hear only the rush of the wind in the grass. It is a fitting climax to this extraordinary film.

he story of Shaka brings to mind that of Siegfried, as it is told in the Wagner Ring cycle. Both men are conceived in illicit unions and born under a curse. Both grow up in rebellion against authority. Both forge for themselves a weapon of magic power, the spear Iklwa and Sieg- fried's sword. Both harbour incestuous passion, Shaka for Nandi and Siegfried for Brunnhilde. Older women, Fricka and Mkabayi, sentence the heroes to die. Both are felled by a spear in the back. Valhalla and KwaBulawayo burn.

Although Shaka Zulu takes place 170 years ago, before the Europeans came, it strikes me as all too topical. The Zulu politicians and generals may wear animal skins rather than Sam Brownes or safari suits, but nevertheless they reminded me of men I have seen, such as Jomo Kenyat- ta, Omeka Ojukwu, Julius Nyerere and, not least, Idi Amin. Some episodes bring to mind the terror and anarchy of the Congo when I was there in 1964, or even when Conrad was there in the 19th cen- tury. KwaBulawayo merits the dying cry of Kurtz, in Heart of Darkness, the man who had gone to Africa to enlighten the natives. His last words were 'The horror! The horror!'

Obviously there was much to admire in Shaka's Zululand. He was, for what it is worth, a military genius. He inspired in the Zulus pride as well as terror. His drastic methods of birth control contained the population. The film-makers emphasise, as did the British who knew him, that Shaka And here's one I charmed earlier.' was a man of enormous intelligence quick, witty and capable, when he chose, of generosity and charm. Yet Shaka Zulu makes me uneasy. It also annoyed all sorts of South Africans.

Old-fashioned Afrikaners have never accepted television, and gave an unfriendly reception to Shaka Zulu. The Conservative MP for Soutpansberg, Tom Langley, said at a meeting in 1986: 'The Afrikaner never was what he is being shown as nowadays. I hope SABC is going to provide us with a parallel of Shaka Zulu for Afrikaners, so that Afrikaner children can also become proud of our history. The SABC is Amer- icanising us.'

The white, English-speaking middle class rejected Shaka Zulu, as they reject most things South African, especially its television. Few of this type I met had seen even one instalment of Shaka. The Weekly Mail, the voice of North Johannesburg `swimming-pool socialism', damned the series with Marxist sociology. The author says that Shaka's cruelties in the film are explained by sorcery and his evil genius:

The effect of recourse to these 'motors' of history is determined by the actions of leaders (spiritual or political) alone, and not by ordinary people. It is a perspective which denies the contribution of the Zulu people to the positive achievements of the Zulu king- dom. It obscures the oppression and ex- ploitation of the people on which the power and wealth of the Zulu leaders was based.

The same sort of attack appeared in newspapers written and read by black supporters of the ANC. The Xhosas, Sothos and other former victims of Shaka, hated the film. Some critics were Zulu, such as the group I met at Sobantu, one of the few townships around Pietermaritzburg that does not support Chief Buthelezi's Inkatha movement. 'No Inkatha member could stay here,' said one of the men in the front parlour, equipped with a television set and a ghetto-blaster. A child slept in the corner, and a woman brought us in rum, beer and succulent pieces of beef. `Do you have Women's Lib?' one of them asked me. 'We feel sorry for you white men who have to go straight home to your wives. We like to talk first with other men, hear the gossip, who's been interned, who's been let out.'

One of the things to which they objected in Shaka Zulu was that it showed a girl sitting beside him in company: 'That would never have been allowed in Zulu society. There'd have been the boys, the young men on one side and the old men on the other.' Objections start to pour forth: 'The architecture was pure American Indian. . . . Shaka would not have been surprised at seeing himself in a mirror. We Zulus used to look into the water as a mirror. . . . Shaka would not have been surprised by a horse.' They believed that no white men actually met Shaka, though Fynn was enjoying sex in Durban. One man de- fended 'the fun of the road': In the history books we were taught we were savages that the missionaries enlightened. The missionaries stopped us using our old sex customs and did not give us any substi- tutes until the pill. Before then, men and women had sex without piercing, without defloration, which gave satisfaction to the woman as well as the man. They both had to use self-control. If a woman got out of line and got pregnant, she would be punished by sending her to live with the old men, who were past having sex. If she married, her partner would get only a small lobola (dow- ry), only one cow. . . Shaka was very par- ticular when it came to sexual matters. He wouldn't allow the men any form of sex for two weeks before fighting.

A Zulu journalist in Pietermaritzburg saw the film Shaka Zulu as P. W. Botha `playing the Zulu card', in the same way that Lord Randolph Churchill played 'the Ulster card'. The Zulu leaders like King Goodwill and Chief Buthelezi gave the film their blessing before it appeared. Chief Buthelezi blames the British for having portrayed Shaka as 'a bestial insane tyrant'. He said that men like Fynn had `scattered sperm around Kwazulu as other men scattered footsteps'. The Afrikaners as well as the Zulus come down hard on the British in Natal. The South African Sunday Times published an essay by Louis du Buisson, author of The White Man Com- eth, a critical appraisal of the early white pioneers in Natal. 'They lied, schemed and cheated their way into the confidence of the Zulu kings,' says Du Buisson. 'They took Zulu girls, and held powers of life and death over thousands.' He blames the British like Fynn for having 'coerced King Shaka into a disastrous war against the Xhosa nation'.

The director of Shaka Zulu, William Faure, read and approved this attack on Fynn and the other British adventurers. Perhaps because I am English, I found something peculiar in this new-found friendship between the Zulus and Boers. Both, it is true, were beaten in war by the British; but they slaughtered each other too. Certainly Faure does not support the present South African government. 'I suf- fered from the education system in the insanity of the Fascist Verwoerd govern- ment,' he told me. 'This government has treated the Zulus like everyone else, with arrogance and incompetence. . . My fami- ly are Treurnicht [right-wing] supporters. They hated the film.' He is hot-eyed, intense and passionate. But might not the film be seen, I suggested, as showing the way for some kind of Zulu-Afrikaner alliance against the Xhosas and English- speaking whites? No, said Faure, 'I don't think this government is bright enough to have sat down seven years ago and thought "How can we manipulate this film?" ' Perhaps not; but Shaka Zulu still makes me uneasy.

Previous page

Previous page