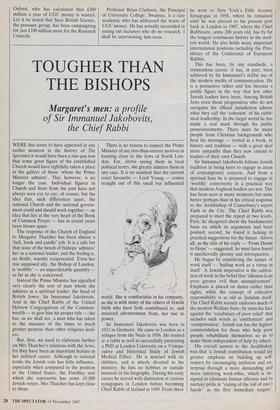

TOUGHER THAN THE BISHOPS

Margaret's men: a profile

of Sir Immanuel Jakobovits, the Chief Rabbi

WERE this series to have appeared at any earlier moment in the history of The Spectator it would have been a sine qua non that some great figure of the established Church would have rightfully taken a place in the gallery of those `whom the Prime Minister admires'. This, however, is no longer the case. Individual figures in Church and State from the past have not always seen eye to eye, of course; but the idea that, such differences apart, the national Church and the national govern- ment could and should work together — an idea that lies at the very heart of the Book of Common Prayer — has in recent years been blown apart.

The response of the Church of England to Margaret Thatcher has been almost a `bell, book and candle' job. It is a safe bet that none of the bench of bishops 'admires' her as a national leader; and the feeling is, no doubt, warmly reciprocated. Even her one supposed ally, the Bishop of London, is 'wobbly' — an unpredictable quantity as far as she is concerned.

Instead the Prime Minister has signalled very clearly the sort of man whom she admires as a spiritual leader: the head of British Jewry, Sir Immanuel Jakobovits. And in the Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Common- wealth — to give him his proper title — she has, as we shall see, a man who has taken to the measure of the times to much greater purpose than other religious lead- ers.

But, first, we need to elaborate further on Mrs Thatcher's relations with the Jews, for they have been an important feature in her political career. Although in national terms the Jewish vote has little influence, especially when compared to the position in the United States, the Finchley seat which she represents has some 10,000 Jewish voters. Mrs Thatcher has kept close to them. There is no reason to suspect the Prime Minister of any less-than-sincere motives in keeping close to the Jews of North Lon- don. For, above seeing them in local political terms, she greatly admires them in any case. It is no accident that the current court favourite — Lord Young — comes straight out of this small but influential world. She is comfortable in his company, as she is with many of the others of Jewish birth who have both contributed to, and received advancement from, her rise to power.

Sir Immanuel Jakobovits was born in 1921 in Germany. He came to London as a refugee from the Nazis in 1936. He trained ar. a rabbi as well as successfully presenting a PhD at London University on a 'Compa- rative and Historical Study of Jewish Medical Ethics'. He is married with six children, and is utterly devoted to his ministry: he lists no hobbies or outside interests in his biography. During his early career he served with distinction at various synagogues in London before becoming Chief Rabbi of Ireland in 1949. From there he went to New York's Fifth Avenue Synagogue in 1958, where he remained until he was elected to his present post back in London in 1967, where the Chief Rabbinate, some 200 years old, has by far the longest continuous history in the mod- ern world. He also holds many important international positions including the Pres- idency of the Conference of European Rabbis.

This has been, by any standards, a tremendous career: it has, in part, been achieved by Sir Immanuel's skilful use of the modern media of communication. He is a persuasive talker and has become a public figure in the way that few other Jewish leaders have been. Among British Jews even those progressives who do not recognise his official jurisdiction admire what they call the 'cohesion' of his rabbi- nical leadership. In the larger world he has made a real mark through his public pronouncements. There must be many people from Christian backgrounds who hear his message — rooted in a book, in history and tradition — with a great deal more sympathy than they now extend to leaders of their own Church.

Sir Immanuel Jakobovits follows Jewish tradition in being keen to engage in areas of contemporary concern. And from a spiritual base he is prepared to engage in `worldly' controversy in a practical way that modern Anglican leaders are not. This has been seen at many moments but none better perhaps than in his critical response to the Archbishop of Canterbury's report Faith in the City. The Chief Rabbi was prepared to meet the report at two levels. First, he disagreed about the fundamental basis on which its arguments had been posited; second, he found it lacking in practical suggestions for the future. Above all, as the title of his reply — 'From Doom to Hope' — suggested, he must have found it unrelievedly gloomy and introspective.

He began by considering the nature of work itself — 'hailing work as a virtue in itself . A Jewish imperative is the cultiva- tion of work in the belief that 'idleness is an even greater evil than unemployment'. Emphasis is placed on duties rather than rights, while the concept of collective responsibility is as old as Judaism itself. The Chief Rabbi warmly endorses much of the modern Welfare State; he turns his face against the 'vocabulary of poor relief that includes such words as 'entitlement' and `compensation'. Jewish law has the highest commendation for those who help poor people rehabilitate themselves so as to make them independent of help by others.

His overall answer to the Archbishop was that 'a Jewish contribution would lay greater emphasis on building up self- respect by encouraging ambition and en- terprise through a more demanding and more satisfying work-ethic, which is de- signed to eliminate human idleness and to nurture pride in "eating of the toil of one's hands" as the first immediate targets'. Those familiar with the Prime Minister's speeches will not fail to recognise this characteristic combination of message the need for social legislation to be effec- tive and the tone of moral exhortation.

Sir Immanuel's criticisms of the Archbishop went further. While being critical of governments that equate success with virtue and of the rapaciousness of the wealthy who exploit those who work for them solely for larger profits, he was not prepared to gloss over — as the Anglicans did — those aspects of economic decline and social deprivation that are 'attributable to the labour unions, whose role is altogether ignored in this report% He also noted that the report had a 'measure of patent political bias'; and pointed out that, however desirable many of its recom- mendations were, it was impossible to judge them as there had not been even an attempt to cost them 'properly in terms of the current state of the national economy.

This does not mean that the Chief Rabbi himself adopts a partisan view. His admir- ers — and detractors — cover all the political parties. Not all his pronounce- ments are welcome to the Conservatives and on some areas — such as Jewish schools — he must have severe reserva- tions about current government policy. Moreover, many leading Labour politi- cians have over the years sought his views and listened to his advice.

There can, though, be little doubt that the present incumbent of 10 Downing Street is his greatest admirer. In 1981 he was knighted at her suggestion — the first time that this has happened to a Chief Rabbi in office. She is known to have had occasional meetings of great length and intensity with him over the years. This goes back a long way: they first began a working relationship when the Prime Minister was Secretary of State for Education. The Chief Rabbi then said to her that her title should be 'Secretary of State for Defence', for 'education is the lifeline of the future'. On this, and on the central position of family life, they are closely in agreement; and the Chief Rabbi clearly welcomes the `revolution in public attitudes' that many believe Margaret Thatcher has achieved.

Future biographers may well have to puzzle over the Jewish contribution to the Prime Minister's political career and thought: hope, even in the face of severe odds, is a particularly Jewish characteristic. The Prime Minister's admiration for Sir Immanuel Jakobovits begins here and ex- tends to the forthright and definitive state- ments that he has taken on difficult moral issues (such as in his two recent articles for the Times, one on homosexuality, the other on Aids: 'Only a moral revolution can contain this scourge'). For himself, Sir Immanuel has very sensibly kept a proper distance from her and will continue to treat her as he does all politicians. Privately, however, he is no doubt pouring down blessings on her head.

Previous page

Previous page