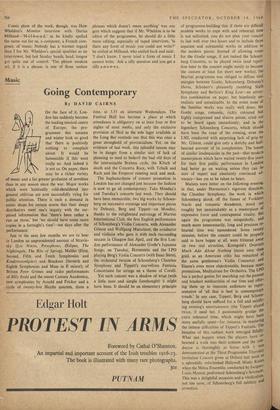

Music

Going Contemporary

By DAVID CAIRNS Just in the next few months we are to hear in London an unprecedented amount of Stravin- sky (Les Noces, Persephone, Edipus, The Nightingale, The Rite of Spring), Mahler (First, Second, Fifth and Tenth Symphonies and Kindertotenlieder) and Bruckner (Seventh and Eighth Symphonies and Mass in E minor); of Britten Peter Grimes and radio performances of Billy Budd and the recent Cantata Academica, new symphonies by Arnold and Fricker and a cycle of twenty-five Haydn quartets, three a time, at 5.55 on alternate Wednesdays. The Festival Hall has become a place at which attendance is obligatory on at least four or five nights of most weeks, and only the exclusive provision of Skol as the sole lager available at the Long Bar reminds one that this was once a great stronghold of provincialism. Yet, on the evidence of last week, this splendid season may be in danger from a similar sort of lack of planning as used to bedevil the bad old days of the interminable Brahms cycle, the Kitsch of death and the Concerto Race, with Tchaik and Bach and the Emperor running neck and neck.

The haphazardness of concert promotion in London has not changed just because the fashion is now to go all contemporary. Take Monday's and Tuesday's concerts last week. They should have been memorable; two big works by Schoen- berg on successive evenings and important pieces by Debussy, Berg and Tippett—on Monday, thanks to the enlightened patronage of Martini International Club, the first English performance of Schoenberg's Violin Concerto, with Alexander Gibson and Wolfgang Marschner, the conductor and violinist who gave it with such resounding success in Glasgow last April, and the first Lon- don performance of Alexander Goehr's Japanese Songs; on Tuesday, Horenstein and the LPO playing Berg's Violin Concerto (with Isaac Stern), the orchestral version of Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony and Tippett's marvellous Fantasia Concertante for strings on a theme of Corelli.

Yet each concert was a shadow of what (with a little taste and simple forethought) it might have been. It should be an elementary principle of programme-building that if there are difficult modern works to cope with and rehearsal time is not unlimited, you do not plan your concert to last well over two hours and to include three separate and substantial works in addition to the modern pieces. Instead of allowing room for the Goehr songs, if not indeed the Schoen- berg Concerto, to be played twice (and repeti- tion later in the concert ought surely to become the custom at least for short new works), the Martini programme was obliged to diffuse vital energies between Goehr, Schoenberg, Debussy's Iberia, Schubert's pleasantly rambling Sixth Symphony and Berlioz's King Lear—an attrac- tive combination on paper, but •hopelessly un- realistic and unrealisable. In the event none of the familiar works was really well done; the Goehr songs, romantic, richly coloured but highly compressed and elusive pieces, cried out to be heard again immediately; and in the legendary Schoenberg Concerto, which should have been the toast of the evening, even the LSO, conducted with surprising lack of grip by Mr. Gibson, could give only a sketchy and half- hearted account of its complexities. The lesson of similar inadequacies in the past—that modern masterpieces which have waited twenty-five years for their first public performance in London had better go on waiting unless they can be sure of expert and absolutely convinced ad- vocacy—has yet to be taken to heart.

Matters were better on the following evening, in that, under Horenstein's vigorous direction, the Chamber Symphony, the work in which Schoenberg shook off the fumes of Verklarte Nacht and romantic decadence, stood out roughly but unmistakably as a masterpiece Of expressive force and contrapuntal vitality. But again the programme was misguidedly, and much more unnecessarily, long and precious re- hearsal time was squandered. Some twenty minutes, before the concert could be properly said to have begun at all, were frittered away on two real atrocities, Korngold's Overture Much Ado About Nothing (more corn than gold, as an American critic has remarked of the same gentleman's Violin Concerto) and Einem's even more objectionable, because more pretentious, Meditations for Orchestra. The LPO has a perfect genius for searching out the poorest and brashest mediocrities of our time and offer- ing them up to innocent audiences as repre- sentative of 'all that is best in contemporary trends.' In any case, Tippett, Berg and Schoen- berg should have sufficed for a full and satisfy,' ing evening's entertainment (the Tippett played twice, if need be). I passionately grudge the extra rehearsal time, which might have been more usefully spent—for instance, in mastering the intense difficulties of Tippett's Fantasia. The beauties of this radiant work emerged ffifullY. What can happen when the players have re- hearsed a work into their systems and the con- ductor is thoroughly at home with it was demonstrated at the Third Programme Thursday Invitation Concert given at Oxford last week I° a splendidly refurbished Holywell Music Rodn1 when the Melos Ensemble, conducted by Jacques- Louis Monod, performed Schoenberg's Serenade. This was a delightful occasion and a vindication: not too soon, of Schoenberg's full subtlety and invention.

Previous page

Previous page