'CAN YOU DRAW PROPERLY IF YOU WANT TO?'

NICHOLAS GARLAND

Cartoonists are not always comical in daily life — but I know two who are. Michael Heath and David Austin both sprinkle their conversation with dry one- liners and, in Heath's case, sudden ramb- ling monologues during which he assumes the accent and character of a type which for some reason or other has irritated or amused him.

I watched them greet each other recently at a Spectator party, mimicking the daft questions cartoonists are sometimes asked.

'You're that cartoonist aren't you? What's 'is name?'

'Do you have a proper job then?'

'Do you know Gerald Scarfe?'

'Do you write your own captions?'

'Can you draw properly if you want to?'

They amused each other like this for some time and then the three of us were approached by a lady guest. 'Oh,' she said, 'you're Michael Heath, aren't you? Tell me, do you write your own captions?'

Michael replied that we'd been through all that, but went on to answer her ques- tions politely until she laughingly asked, 'Tell me, why was there such a fuss when that Mark Boxer died? — I mean, what was it about him?'

In one way or another, we simultaneous- ly replied that Boxer had been a disting- uished artist, implying that once that was understood her question, while remaining offensive, required no further answer.

I cannot be absolutely certain but I don't think the lady would have asked in such a frivolous way about the death of a so-called fine or serious artist. 'Why was there such a fuss when that Henry Moore died?' The work — and even the deaths — of comic artists tend to be considered lightly in this country. This is not true of other art forms: it is quite common for serious or classical actors to acknowledge the debt they owe to a comedian. 'I learned everything I know, laddie, about timing, projecting, handling props, character acting, etc from Max Miller . . . Frankie Howerd . . . Ted Ray . . . Jack Benny,' and so on. Such tributes may be more than a little condescending, but they are genuine nevertheless.

But I do not remember any artist, other than another cartoonist, ever paying such a tribute to Leach for example or Vicky or Rowlandson. A sort of class distinction exists in art, by whose rules comic art is seen as an amusing sideshow or light relief to the main drama of life rather than as a serious art form in its own right. By this definition it is seen as trivial. Even when one artist is a master of both fine and comic art there is a tendency to separate his two styles and think of them as independent of each other. The comic art is perhaps seen as inspired mucking about, but the fine art is the really serious stuff.

In fact something closer to the opposite may be true. Take the work of Edward Lear. He was a good conventional artist but a comic artist of genius. His two styles could scarcely look more different but the one is by no means independent of the other. All his comic drawings, the owly owls and the grasshoppery grasshoppers and the strange little ladies and gentlemen which illustrate his nonsense verse, were drawn by a hand guided by hours and hours of patient study from nature. The briefest glance at his work reveals this to be true. You have to know a great deal about geese to be able to draw one as simply and accurately as he could. His comical animals are brilliant caricatures of whole species. The simplification and distortions all de- pend on a profound knowledge of the real creatures.

This hinterland of learning gives his slightest scribble its strength. But what raises this work so far above the rest is something that comes from another source and which does not contribute at all to his more conventional work. Indeed it is perhaps deliberately excluded.

In his nonsense verse and in their lively illustrations he taps straight into his own emotions and preoccupations. Themes such as loneliness, loss, love, regret and hope delicately enrich the apparently in- consequential antics of his touching and perplexed heroes. His jokes, whether he intended it or not, are unmistakably sad as well as funny. Even with as humorous an artist as Lear the word 'comic' does not seem entirely satisfactory to describe this aspect of his work. I do not know how consciously he included the melancholy side of his personality in his comic work. I would guess that somewhere he had a very shrewd idea of what he was doing, and if I'm right and he was consciously expressing his true feelings through his nonsense drawings and verses, then he was doing something very ambitious and rather ad- vanced for his time. In the years that have followed his death in 1888 many artists have set out to represent or convey emotions in their painting and graphic work. Matisse wrote of wanting his pictures to have the lightness and joyousness of springtime. Van Gogh, in a letter to his brother Theo about a painting of his own bedroom, said the picture should be suggestive . . of rest or of sleep in general. In a word, to look at the picture ought to rest the brain or rather the imagination.'

Comic art too may reach far beyond trying to amuse or delight. It may go further even than the bitter-sweet melan- choly of Edward Lear and set about the most serious and passionate of all human feelings — from the lust for power and money, through lust itself, to love and the battle of the sexes and the confrontation of age and youth. If comic art may deal with such serious, even solemn, matters it is possibly less of a sideshow or cul-de-sac than it might seem to us.

Perhaps the first artists to attempt the representation of emotions or human traits such as greed, hypocrisy or cunning were comic artists. Or it could be that in order to study and record the manifestation of subtle, complex qualities of this kind artists had to invent a style combining observa- tion with specific distortions and exaggera- tions which, however serious its original intent, we now call comic. There is, howev- er, a complication caused by the word 'comic' at the borderline where art which is broadly speaking in a comic mode crosses over into deadly seriousness. I do not refer to artists who allow their work to be touched with unhappiness as Edward Lear does, or who, like Charles Addams or Ronald Searle cheerfully indulge their taste for black humour. I mean those artists who frankly pour out their rage and distress and contempt in — I have no other word for it at the moment — comic form. This happens frequently in political car- tooning and satirical art.

The great cartoonist Vicky was famous for his serious cartoons when drawings of bloated babies from the third world, or freezing old age pensioners, suddenly appeared where a joke was expected. His friends called this his 'Oxfam style'.

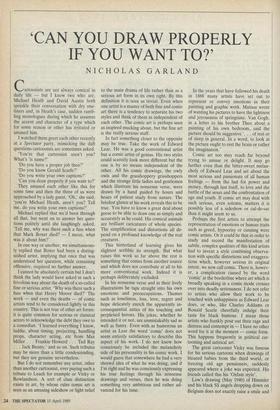

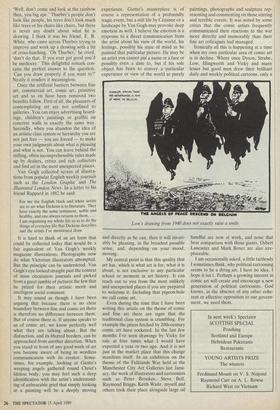

Low's drawing (May 1940) of Himmler and his black SS angels dropping down on Belgium does not exactly raise a smile and was not intended to. It feels downright odd to call it comic art. An even more extreme example of this complication is Daumier's `Rue Transnonain', his response to an act of appalling brutality committed by some rampaging infantrymen in 1834. The medium (lithography), the expressed out- rage, the bitter social comment could be said to belong to the artist's political cartoonist side. But the work cannot be pigeonholed like that. It is probably more closely related to some of Goya's pictures of violent death and inner turmoil than it is to anything else.

At extremes of this kind any attempt to separate fine and comic art collapses. The class system breaks down. At this point it might sound reasonable to ask whether Gericaules 'Raft of the Medusa' with its Implicit criticism of the government of the

day is actually a very, very big political cartoon. And if it is, Goya's 'May 14th' and Picasso's `Guernica' are also huge complex cartoons. Obviously they are not. But if my argument that all art is one, that there is no fundamental difference, is right, then in another way they are. At the very least I can claim there is no clear, stable boundary between fine and comic art.

Both can be looked at and enjoyed in exactly the same way; both require for their successful execution the same skills of drawing, composition and sensitivity to colour and tone; both can play powerfully on our emotions. Yet although they are equal in these respects, there are of course real differences.

While all artists are observers, comic artists are also critics or commentators. When one looks at a cartoon there is you, and there are the characters in the draw- ing; but there is also the cartoonist, speak- ing through the medium of the drawing. This is not necessarily so in all works of art, but one could say it was an invariable of comic art, and particularly of political cartooning.

Another difference is revealed by what may be attempted within the confines of the two modes. Comic art does not lend itself to the general appreciation and celebration of beauty or glory or to the praising of individuals. Caricature with its push towards distortion and exaggeration invariably reduces the dignity and author- ity of its subjects. It may be good-natured in intent, but, however faintly, it includes a mocking laugh. Fine art is both more profound and more ambitious — its range is wider, touching as it does on the entire universe of the human condition, while comic art selects, and touches more lightly, here and there. It is interesting that comic art needs people: men, women, children or anthropomorphised animals; and often a Daumier's 'Rue Transnonain' — bitter social comment' caption, or words to complete the idea or point contained in the work. For instance you could not have a comic still life. A surrealist still life could make you smile, as might a recognisable parody of another artist's work, or a still life used to illustrate a written article. But in each case there is a context in which the picture makes logical, verbal sense. Jokes belong to the verbal universe in the way that a still life by Chardin does not. One could not have a comic still life standing alone as the Char- din can; and for the same reason it is equally difficult to imagine a comic land- scape. There may be many comic drawings that have as a central feature a landscape. I am thinking of the one with the man and his young son. Before them are flowery meadows, forests, pretty streams and waterfalls stretching in idyllic loveliness as far as they can see. The father, with despair and something like panic on his face, is saying to his expressionless offspring, 'It's not advertising anything, damn it.'

Today, because we all know that our children's sensibilities are being blunted by television, we identify with the adult and laugh at the joke. In a hundred years' time the descendants of this age may not be able to read the caption. They will simply see a landscape with figures, and a piece of comic art will have become transformed into, albeit quaint, fine art.

This already happens to some extent with the social and political satires of the 18th and 19th centuries. Most of us do not know enough history to be able to read the drawings as they were intended to be understood. So, because we don't get the joke, what we see are lively pictures of a time we find fascinating and romantic, and we enjoy the arrangement and depiction of costume and furniture and landscape rather than the comment. It follows that we are inclined to think of the creators of these scenes as artists rather than cartoon- ists; and bereft of its original meaning comic art is, as it were, smuggled across the border into fine art country — right under our noses.

Most cartoons published during the 19th century showed carefully studied ordinary- looking people saying or doing silly things. The artists worked from models to get posture and the folds of garments correctly drawn and thus the 'distinction' between fine and comic art was not so apparent. It may have been New Yorker cartoonists who pioneered the reversal of this system by drawing heavily simplified representa- tions of people who were often saying quite ordinary things. I'm thinking of a New Yorker cartoon of a bad-tempered, middle- aged woman, her mouth drawn in an 'H' of disapproval, looking up at a magnificent, starry sky and saying, 'Well, it doesn't make me feel insignificant.'

James Thurber is one of the greatest artists in this modern style. He invented a whole world which, however dreamlike and peculiar it may seem from outside, is entirely recognisable and familiar once you are in it. That is why when it was reported to him that someone had said, 'No one could find Thurber's women attractive,' he replied with crushing finality, `Thurber's men do.'

The person who made that statement about Thurber's women had not taken a necessary step away from the idea that there is a 'proper' way of drawing, and that `proper' drawing is good drawing.

But a good drawing is not necessarily one that comes closest to an ideal achieved by Raphael. A good drawing may be one that most completely and richly conveys what it is intended to convey. The silhou- ette on street signs indicating to motorists the likely presence of children crossing the road is a better drawing in that context than a study of a child by, say, Rubens.

It is impossible to think of anyone who could do a better drawing for the purpose than Thurber's scene of a woman standing at a window and snarling at her husband, 'Well, don't come and look at the rainbow then, you big ape.' Thurber's people don't look like people, his trees don't look much like trees or his chairs like chairs, but there is never any doubt about what he is drawing. I think it was his friend, E. B. White, who came across Thurber trying to improve and work up a drawing with a bit of cross-hatching. 'Oh Thurber,' he cried, 'don't do that. If you ever got good you'd be mediocre.' This delightful remark con- tains the perfect answer to the question, 'Can you draw properly if you want to?' Neatly it renders it meaningless.

Once the artificial barriers between fine art, commercial art, comic art, primitive art and so on have been removed two benefits follow. First of all, the pleasures of contemplating art are not confined to galleries. You can enjoy advertising hoard- ings, children's paintings or graffiti on concrete walls in exactly the same way. Secondly, when you abandon the idea of an artistic class system or hierarchy you are not just free — you are forced — to make your own judgments about what is pleasing and what is not. You can leave behind the stifling, often incomprehensible rules made up by dealers, critics and rich collectors and find art in the most unexpected places.

Van Gogh collected scores of illustra- tions from popular English weekly journals such as the London Graphic and The Illustrated London News. In a letter to his friend Rappard in 1882 he said: For me the English black and white artists are to art what Dickens is to literature. They have exactly the same sentiment, noble and healthy, and one always returns to them. . . . I am organising my whole life so as to do the things of everyday life that Dickens describes and the artists I've mentioned draw.

It is hard to think of an art form that could be collected today that would be a fair equivalent of Van Gogh's weekly magazine illustrations. Photographs now do what Victorian illustrators attempted. But the principle can be understood. Van Gogh's eye looked straight past the context of mass circulation journals and picked from a great jumble of pictures the few that he prized for their artistic merit and intelligent social comment.

It may sound as though I have been arguing that because there is no clear boundary between fine and comic art there is therefore no difference between them. But of course there is. If anyone speaks to us of comic art, we know perfectly well what they are talking about. But the distinction, and its blurred borders, can be approached from another direction. When you stand in front of any good work of art you become aware of being in wordless communication with its creator. Some- times, for example, looking at Giotto's weeping angels gathered round Christ's lifeless body, you may feel such a deep identification with the artist's understand- ing of unbearable grief that simply looking at a painting will be a deeply moving

experience. Giotto's masterpiece is of course a representation of a profoundly tragic event, but a still life by Cezanne or a landscape by Van Gogh may provoke deep emotion as well. I believe the emotion is a response to a direct communication from the artist about his view of the world, his feelings, possibly his state of mind as he painted that particular picture. He may be an artist you cannot put a name or a face or possibly even a date to, but if his sole object has been to convey a particular experience or view of the world as purely

and directly as he can, then it will invari- ably be pleasing, in the broadest possible sense, and, depending on your mood, moving.

My central point is that this quality that art has, which is what art is for, what it is about, is not exclusive to any particular school or moment in art history. It can reach out to you from the most unlikely and unexpected places if you are prepared to welcome it. Including that pigeon-hole we call comic art.

Even during the time that I have been writing this article on the theme of comic and fine art there are signs that the traditional class system is crumbling. For example the prices fetched by 20th-century comic art have rocketed. In the last few months I've seen drawings by Vicky for sale at four times what I would have expected a year or two ago. And it is not just in the market place that this change manifests itself. In an exhibition on the theme of the Falklands War held at the Manchester City Art Galleries last Janu- ary, the work of illustrators and cartoonists such as Peter Brookes, Steve Bell, Raymond Briggs, Keith Waite, myself and others took their place alongside large oil paintings, photographs and sculpture rep- resenting and commenting on those stirring and terrible events. It was noted by some critics that the comic artists frequently communicated their reactions to the war more directly and memorably than their fine art colleagues had managed.

Ironically all this is happening at a time when my own particular area of comic art is in decline. Where once Dyson, Strube, Low, Illingworth and Vicky and many lesser but good men drew their brilliant daily and weekly political cartoons, only a handful are now at work, and none that bear comparison with those giants. Osbert Lancaster and Mark Boxer are also irre- placeable.

I am occasionally asked, a little tactlessly I sometimes think, why political cartooning seems to be a dying art. I have no idea. I hope it isn't. Perhaps a growing interest in comic art will create and encourage a new generation of political cartoonists. God knows, in the absence of any other cohe- rent or effective opposition to our govern- ment, we need them.

Previous page

Previous page