Outside the Walls

By CHARLES PANNELL, MP

(CANNOT at the moment under the Capital Punishment Amendment Act, 1868, remove the body. It would have to be done by legis- lation and while there is doubt I do not think I can authorise Government support for legis- lation on this matter.'

So said Mr. R. A. Butler on June 15, 1961, and it was his last slim reason for not doing simple justice to the relatives of the late Timothy John Evans. He had already acknowledged in the same speech that if 'the facts as they are now known had been known in 1950, the jury Would not have found that the case against Evans had been proved beyond all reasonable doubt.'

And so just over a month later the Member for Leeds West asked leave of the House 'to bring in a Bill to amend Section Six of the Capi- tal Punishment Amendment Act of 1868.' Leave Was unanimously granted, but the opportunity to proceed further has not arisen since then.

Section Six stipulates that 'the body of every Offender executed shall be buried within the walls of the prison within which judgment of Death is executed on him' and what my Bill seeks to do is to add to the end of the section the following words:

Provided also that if one of Her Majesty's Principal Secretaries of State thinks fit, he may by writing direct the body to be handed over (either unconditionally or subject to such con- ditions as he may impose) for burial elsewhere than within the walls of the prison to a person who appears to him to be the next of kin or one of the next of kin of the offender.

This would be in keeping with the recommen- dation of the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment, which has now been implemented by the judges, that the grisly old form of sen- tence be done away with. 'That you be taken hence to the gaol . . . you be taken thence to the place of execution . . . to be hanged by the neck . . . and that your body be afterwards buried within the precinctS of the prison.' That rather ghoulish rigmarole has gone out and the judge now simply says: You have been convicted of capital murder and by the law of this country the penalty is that you suffer death in the manner authorised by law.

Mr. Butler's difficulty would go if my Bill became law—for he could then allow under Proper safeguards the remains of Evans (and Perhaps others) to be buried in a manner more seemly and give some comfort to his relatives.

The 1868 Act was brought in to do away with Public hanging and the natural corollary was also to do away with the very public burials— Or sometimes worse—of those for whom the sen- tence was death. Looking back through those °Id debates one is struck by the fact that the arguments were always about the hanging, not about the burying. Was it a greater deterrent to take it away from the mob? One hundred thousand people tried to see Fauntleroy executed in 1824. One MP condemned the proposed change as 'private assassination.' Little was said in the House about' the remains, but there was a long history and a collective memory about this.

In 1868 there were still many people alive who would recall the case of Henry Cook in 1831—a ploughboy of nineteen who could neither read nor write. If not exactly a village Hampden, he had got mixed up in the last Labourers' Revolt. His wages but ten shillings per week, he had gone round with other local rebels demanding money. For this he would have got off with transportation for life, but he struck a blow at a magistrate—an influential Baring—and knocked his hat off, and with one

A

BILL

TO

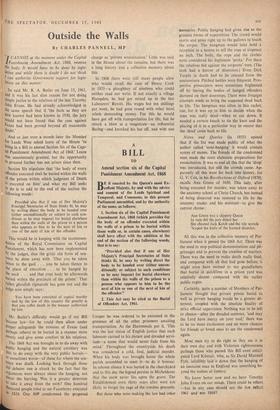

Amend section six of the Capital Punishment Amendment Act, 1868 E it enacted by the Queen's most Ex-

cellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows: 1. Section six of the Capital Punishment Amendment Act, 1868 (which provides for the body of an offender executed within the walls of a prison to be buried within those walls or, in certain cases, elsewhere) shall have effect with the addition at the end of the section of the following words, that is to say: "Provided also that if one of Her Majesty's Principal Secretaries of State thinks fit, he may by writing direct the body to be handed over (either uncon- ditionally or subject to such conditions as lie may impose) for burial elsewhere than within the walls of the prison to a person who appears to him to be the next of kin or one of the next of kin of the offender."

2. This Act may be cited as the Burial of Offenders Act, 1961.

Cooper he was ordered to be executed in the presence of all the other prisoners awaiting transportation. As the Hammonds put it, 'This was the last vision of English justice that each labourer carried to his distant and dreaded servi- tude—a scene that would never fade from his mind.' Throughout the countryside his death was considered a cold, foul, judicial murder. When his body was brought home the whole parish, assembled to meet it—to do it honour. In solemn silence it was buried in the churchyard and to this day the legend persists in Micheldever that the snow never lies upon the grave. The Establishment even thirty years after were not likely to forget the rage of the voteless peasants.

But those who were making the law had other memories. Public hanging had given rise to the grossest forms of superstition. The crowd would storm and press right up to the gallows to touch the corpse. The hangman would later hold a reception in a tavern to sell the rope at sixpence an inch. The body, the rope and the clothes were considered his legitimate 'perks.' For these the relatives bid against the surgeons' men. (The mob had a horror of dissection.) Even Dick Turpin in death had to .be rescued from the anatomisers. Pitched battles were frequent. Pros- pective prosecutors were sometimes frightened off by having the bodies of hanged offenders dumped on their doorsteps. There were frequent attempts made to bring the supposed dead back to life. The hangman was often in this racket, too, for it was up to him to decide when the man was really dead—when to cut down. It needed a certain knack to tie the knot and the placing of it in a particular way to ensure that the 'dead' came back to life.

Notes and Queries (in 1855) opined that if the list was made public of what the author called 'semi-hanging' it would contain scores of names. The friends of the condemned man made the most elaborate preparations for resuscitation. It was to end all this that the 'drop' was introduced, but still the crowds came. Ap- parently all this went far back into history, for G. V. Cox, in his Recollections of Oxford (1870), recalls Ann Green of 1650. This lady, after being executed for murder, was taken away to the anatomy school at Christ Church, but instead of being dissected was restored to life by the anatomy reader and his assistant—to give the current rhyme:

Ann Green was a slippery Quean In vain did the jury detect her She cheated lack Ketch and the vile wretch 'Scaped the knife of the learned dissector.

All this was in the collective memory of Par- liament when it passed the 1868 Act. There was the need to stop political demonstrations and pil- grimages and to prevent the creation of martyrs. There was the need to make death really final, and compared with all that had gone before, it might even have seemed to our grandfathers that burial in quicklime in a prison yard was relatively decent compared with the earlier public orgies.

Certainly, quite a number of Members of Par- liament thought that private prison burial as well as private hanging would be a greater de- terrent, coupled with the absolute finality of strict official supervision. Nothing was to be left to chance—after the dreaded sentence, 'and may the Lord have mercy on your soul,' there was to be no more excitement and no more chances for friends or loved ones to see the condemned again.

Most men try to do right as they see it in their own day and with Victorian righteousness perhaps those who passed this Bill even antici- pated Lord Kilmuir, who, as Sir David Maxwell Fyfe, infallibly laid it down that the hanging of an innocent man in England was something be- yond the realms of fantasy.

We know better now and we have Timothy John Evans on our minds. There could be others —but in any case should not the law reflect 1961 and not 1868?

Previous page

Previous page