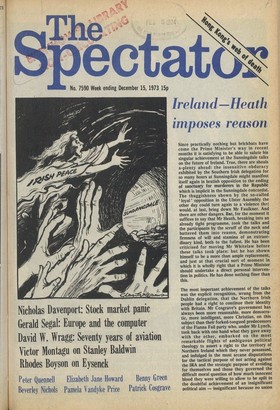

Ireland Heath imposes reason

Since practically nothing but brickbats have come the Prime Minister's way in recent months it is satisfying to be able to salute his singular achievement at the Sunningdale talks on the future of Ireland. True, there are shoals a-plenty ahead: the insensitive obduracy exhibited by the Southern Irish delegation for so many hours at Sunningdale might manifest itself again in brutish opposition to the ending of sanctuary for murderers in the Republic which is implicit in the Sunningdale concordat. The thuggishness shown by the so-called ' loyal ' opposition in the Ulster Assembly the other day could turn again to a violence that would, at last, bring down Mr Faulkner. And there are other dangers. But, for the moment it suffices to say that Mr Heath, breaking into an already tight programme, took the talks and the participants by the scruff of the neck and battered them into reason, demonstrating firmness of will and stamina of an extraordinary kind, both to the fullest. He has been criticised for moving Mr Whitelaw before these talks took place: but he has shown himself to be a more than ample replacement, and just at that crucial sort of moment in which it is wholly right that a Prime Minister should undertake a direct personal intervention in politics. He has done nothing finer than this.

The most important achievement of the talks was the explicit recognition, wrung from the Dublin delegation, that the Northern Irish people had a right to continue their identity with Britain. Mr Cosgrave's government has always been more reasonable, more democratic, more intelligent, more Christian, on this subject than their forked-tongued predecessors of the Fianna Fail party who, under Mr Lynch, took back with one hand what they gave away with the other, embarked on the most remarkable flights of ambiguous political theology to assert a right to the territory of Northern Ireland which they never possessed, and indulged in the most arcane disputations for the tactical purpose of not acting against the IRA and the strategic purpose of avoiding for themselves and those they governed the difficult moral question of how much innocent blood they were willing to allow to be spilt in the doubtful achievement of an insignificant political aim — insignificant because no union between the two parts of Ireland that was not one of hearts could have worked.

What of the men of violence? If the semiunited police authority is allowed to operate, if the army continues to prosecute its war against the killers both Protestant and Catholic in Ulster, if those murderers fleeing from British forces meet their just deserts at the hands of the law enforcement bodies of the Irish Republic, and if the Executive and the Assembly as well as the Council pursue placatory social policies, then they can be extirpated. Much of that depends on Mr Cosgrave and his ministers, but a lot also depends on the Protestants of Ulster. That province will never again enjoy the measure of autonomy it had under Stormont, as Mr Faulkner will never again enjoy his quondam authority as Prime Minister. But that is just, since the oppression of Catholics for fifty years took away from the Protestants of Ulster their unfettered right to deny any identity with Ireland and any serious identity with British standards: their rights remain, but fettered. The two men on whom much now depends are Mr Faulkner and Mr Fitt — whose courage, Incidentally, is beyond praise, since the murder gangs among his co-religionists have often threatened him, and since he has often defied them in his determination to make powersharing work — and they will be on the rack of politics and violence in the coming months. Let us give them both every support, seeking as they are to create a commonwealth of three interests — British, Ulster and Irish — which truly reflects the composition, determined historically, socially and politically, of the peoples of these islands.