Theatre

Transgressor

Christopher Edwards

The Pope's Wedding (Royal Court) The Pope's Wedding was Edward Bond's first play, written when he was 28 years old, and performed at the Royal Court in 1962. It was a brilliantly promising debut, and remains my favourite Bond play. Indeed it is virtually the only Bond play I can sit through without irritation; like so many left-wing playwrights who emerged from obscurity in the Sixties to fall into the eager and warm embrace of the subsidised theatre, Bond distorts his material to satisfy ideological ends. This approach creates enormous disappoint- ment when foisted upon the innocent theatre goer and is a betrayal of artistic instincts. Drama provides a unique oppor- tunity to body forth life in a disinterested way, without, that is, the playwright stick- ing his grubby finger on the scale like a corrupt grocer. Bond is guilty of this all the time, and as any reading of his Prefaces will reveal he is a happy and committed transgressor. Bond's reputation as a leading Sixties socialist propagandist was founded on the shock value of his preoccupation with violence. He was presenting, so he main- tained, a true picture of British civilisation in which the lower classes were 'deprived' and driven to destructive behaviour by, predictably, the 'institutionalised' violence of society. At times Bond was capable of coining arresting and lurid flights of rhetor- ic. You cannot ride on a bus or strike a match, he said, without committing canni- balism. 'You don't eat anybody physically, but you eat their despair, you eat the waste of their lives . . . we clothe the sides of our cars with human skin, because people have been abused to make them.' More charac- teristically, however, it is the drone of the solemn rationalist that greets you from the pages of his many Prefaces: 'The ruling mythology has a spurious plausibility. . . . No one could deny that human beings can be violent. But the argument is about why they are violent. Human violence is contin- gent not necessary, and occurs in situations that can be identified and prevented . . . Plato wanted his ruler to knowingly lie [sic]. The members of our ruling class are riot liars but — worse — fools who believe their own mythology.' To which you might reply that there are bigger *fools, yea and worse mythologies. But the question is, can a man carrying all this ideological baggage write a decent play? In the days of his youth he could.

The Pope's Wedding is beautifully com- posed. The dialogue is effortlessly natural, and the tale unfolds in a manner that is both apparently casual and at the same time utterly arresting. Bond introduces a group of young East Anglian labourers who we first meet hanging about a street corner. They fight and talk about girls and beer. A more authentically ordinary bunch of boyos you could not wish to meet, but it is exactly the precision of Bond's observa- tion that makes them interesting. The production breathes life from the very first scene. Gradually one of the young men, Scopey, emerges as the principal character. First he distinguishes himself on the village cricket pitch in a cleverly staged scene which pits him, successfully, against the village fast bowler. Scopey wins the match and, in good Boy's Own style, gets the girl, Pat, as a reward. They marry, and the rest of the play plots how Scobey goes off the rails. What brings about this downfall is an obsession with an old agoraphobic tramp, Alen, who lives in a tiny hut outside the village. Just before the cricket match we have met Men, meticulously stacking newspapers on his floor, saying nothing but freezing with panic as he hears a bang on the door. Who it is outside in the dark we never learn, but this little scene, which takes place, spectrally, at the back of the stage, introduces a note of tension that mounts from this moment to the end.

It turns out that Pat `does' regularly for old Alen, a duty she inherited from her dead mother. Scobey insists on taking over her role, visits the old man and establishes a brittle confidence between them. Old Alen has dropped out. Why? What wisdom does he possess? Did he run after Pat's mother in his youth? Will he be Scobey's friend? Scobey becomes fascinated by Alen's life. He accepts the gift of an overcoat which makes him look exactly like his mentor. Immediately upon receiv- ing the coat he rips open the pockets, which have been sewn up, to see if there are any photographs of the past which may offer clues. Exactly what he is after is unclear, but he wishes to create some sort of meaning for himself out of his associa- tion with Alen; as the title wryly suggests, the chances of success are not high. Alen is not up to Scobey's expectations. He is just an empty and rather stupid old man, although Tony Rohr succeeds in making him touchingly human, funny and vulner- able. In the end Scobey murders him.

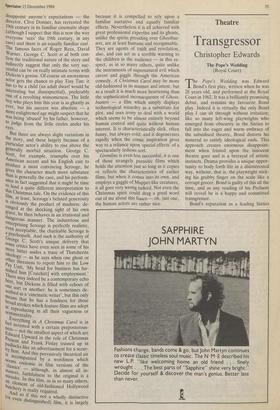

What is the reason for this act of violence against an innocent old man? Scobey, and the rest of the accurately drawn characters, come from pretty stul- tifying backgrounds which offer them only the slenderest prospects of improving their lot. But the play, mercifully avoids advan- cing any explicit analysis. There is no intrusive 'cycle of deprivation', and no looming presence of a governing class. At this early stage in his career Bond's artistry was paramount, and any explanation for what takes place is a matter of tentative inference based upon the prime evidence of living character. Max Stafford Clark has elicted acting of the very highest order from his cast, in particular Gary Oldman as Scopey. This is a compelling evening in the theatre and an absolutely excep- tional production of a remarkable play.

'Is there a second opinion in the house?'

Previous page

Previous page