Exhibitions

Emil Torday and the Art of the Congo 1900-1909 (Museum of Mankind, till November 1992)

Art of Africa

Giles Auty

Those who bemoan, occasionally, the absence of exhibitions which excite them in Cork Street often overlook a wonderful resource not a spear's throw distant. The Ethnography Department of the British Museum is in nearby Burlington Gardens. Those tired of the latest caperings of today's neo-Fauves in the galleries of British art's golden furlong can thus repair conveniently to the Museum of Mankind to examine some of the artefacts which in- spired the authentic Fauves some 80 years earlier.

As one who took part in the original Fauve exhibition at the Salon d'Automne in 1905, Maurice de Vlaminck is often credited with introducing Derain, Matisse and Picasso to African sculptures. He had seen these first in the Paris Trocadero and in 1904 acquired examples of his own. The violent drama yet apparent innocence of African carving spoke strongly to artists who were flexing their muscles at the dawn of a new century, anxious to put the tired mannerisms of official 19th-century art behind them. Fascination with the myste- rious heartlands of the African continent had been excited also by Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, published in 1902, which was set in what was then the Congo Free State. From 1886 to 1908 this vast territory was administered under the per- sonal rule of Leopold II, King of the Belgians. The commercial exploitation of what became the Belgian Congo — and 'Llmm, nice use of space.' much later Zaire — first brought a young Hungarian to the area.

Emil Torday was born in 1875 and was thus an almost exact contemporary of Vlaminck and the other Fauves. At first, his interest in ethnography was simply that of the European amateur: he collected artefacts and learned local languages at the same time as pursuing big game and a commercial career. Torday soon learned to love central Africa and its peoples and expressed the wish never to return to a Europe where the cultures of Africa had been regarded for so long as primitive and barbaric. He was to find that such adjec- tives were more apt descriptions of the exploitation of Africans by Europeans. Hundreds of thousands perished through forced labour in the burgeoning rubber industry or through famine caused by a related neglect of local agriculture.

Torday's work is often undervalued and overlooked today, not least because he was not a trained anthropologist, and thus not a follower of what has become perceived as proper academic practice in the field. Yet Torday was to become, in effect, an unofficial agent and formal collector for the British Museum. The 3,000 central African artefacts he collected for that institution may have been selected some- times for reasons of European aestheticism rather than 'correct' anthropological pur- pose but I admit to being rather glad of this. The 500 objects on display for the next two years at the Museum of Mankind are a selection from the parent, British Museum collection. These include marvel- lous examples of carved wooden figures and masks, richly patterned textiles, cere- monial weapons, pots, hairpins, charms and ritual objects. On the whole, the figures are more naturalistic in style than the more angular Parisian examples which so excited Picasso. Somewhat disappoin- tingly, Kuba carving is thus not one of the direct sources of Cubism, though amazing- ly, during the first world war, French military propaganda did manage to credit the Germans with the invention of Kub- ism, a degenerate art form which was playing a part in sapping French national morale.

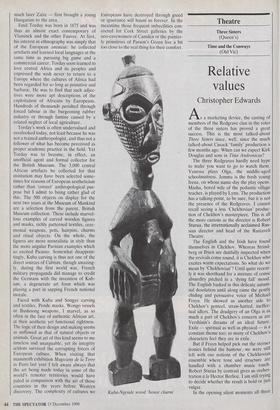

Faced with Kuba and Songye carving and textiles, Pende masks, Wongo vessels or Bushoong weapons, I marvel, as so often in the face of authentic African art, at their aesthetic yet functional rightness. The logic of their design and making seems as unflawed as that of natural objects or animals. Great art of this kind seems to me timeless and unarguable, yet its integrity seldom survived the corrupting forces of European culture. When visiting that mammoth exhibition Magiciens de la Terre in Paris last year I felt aware always that the art being made today in some of the world's remoter territories would have paled in comparison with the art of those countries in the years before Western discovery. The complexity of cultures we

Europeans have destroyed through greed or ignorance will haunt us forever. In the meantime those frequent imbecilities con- cocted for Cork Street galleries by the neo-cavewomen of Camden or the painter- ly primitives of Parson's Green live a bit too close to the real thing for their comfort.

Kuba-Ngende wood 'house charm'

Previous page

Previous page