Theatre

Three Sisters (Queen's) Time and the Conways (Old Vic)

Relative values

Christopher Edwards

As a marketing device, the casting of members of the Redgrave clan in the roles of the three sisters has proved a great success. This is the most talked-about Three Sisters since, well, since the much talked-about Cusack 'family' production a few months ago. When can we expect Kirk Douglas and sons in Titus Andronicus?

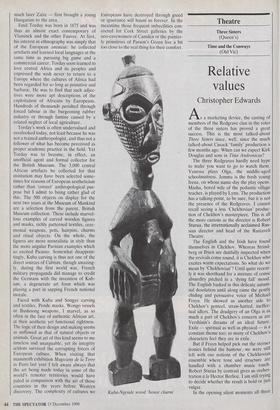

The three Redgraves hardly need hype to make you want to go to watch them. Vanessa plays Olga, the middle-aged schoolmistress. Jemma is the fresh young Irena, on whose name-day the play opens. Masha, bored wife of the pedantic village teacher, is played by Lynn. The production has a talking-point, to be sure, but it is not the presence of the Redgraves. I cannot recall seeing a less `Chekhovian' produc- tion of Chekhov's masterpiece. This is all the more curious as the director is Robert Sturua, the internationally acclaimed Rus- sian director and head of the Rustaveli Theatre.

The English and the Irish have found themselves in Chekhov. Whereas Strind- berg or Ibsen are dutifully inspected when the revivals come round, it is Chekhov who excites warm expectations. So what do we mean by `Chekhovian'? Until quite recent- ly it was shorthand for a mixture of comic absurdity pitched in a 'dying fall' mood. The English basked in this delicate autum- nal desolation until along came the gently chiding and persuasive voice of Michael Frayn. He showed us another side to Chekhov's genteel, straw-hatted, ineffec- tual idlers. The drudgery of an Olga is as much a part of Chekhov's concern as are Vershinin's dreams of an ideal future, Exile — spiritual as well as physical — is a constant theme too; so many of Chekhov's characters feel they are in exile.

But if Frayn helped pick out the sterner ironies behind the humour, we were still left with our notions of the Chekhovian ensemble where tone and structure are handled with a chamber music touch. Robert Sturua by contrast gives us orches- tration a la Hector Berlioz. I am still trying to decide whether the result is bold or just vulgar.

In the opening silent moments all three girls glide forward spectrally, like spirits revisiting old haunts. Vanessa Redgrave's crop-haired Olga opens the grandfather clock and puts the hands back. Then the play begins. Adroit or heavy-handed? It is certainly one of the quietest moments in the production. Lynn Redgrave's Masha is not the usual brooder. She stomps coarsely about the stage. Noise and rude physicality are the hallmarks of the Prozorov house- hold. This pays certain dividends. For example, the physical intimacy between Andrey (Jeremy Northam) and his vulgar fiancée Natasha (Phoebe Nicholls) can never have been so clearly depicted. She is sexy, knows it and exploits Andrey's sen- suality to get her own way about the mummers, Irena's room etc. This is an original depiction of the way Natasha is able to gain domestic power. Even Masha's spirited schoolteacher husband Kulygin (Michael Carter) is several cuts above the usual put-upon wimp. You can see why Masha, when young, might have been impressed. On the other hand, the point Masha makes about how vulgarity upsets her seems a bit thick coming from her. No one's manners are particularly refined. Slyony (Adrian Rawlins) has some excuse for his oddities, and so maybe we are not too surprised when he suddenly starts walking on his hands at a critical emotional moment. But the lack of contrast in Stuart Wilson's Colonel Vershinin is a loss. No hand-stands, but there is too much of the parade ground about him. None of the actors — Vanessa and Jemma Redgrave excepted — seems willing to allow the shifts in mood to weave their own delicate atmosphere. This is not a production for those wishing to aquaint themselves with old, loved friends. Is all this robustness more authentically Russian? If so, does this help? As you can see, this reviewer is not entirely convinced.

Three Sisters is about the way life mocks hope. So too, in its way, is J.B. Priestley's Time and the Conways, which is revived at the Old Vic with members of yet another acting tribe in key roles: Joan Plowright is Mrs Conway, Tamsin and Julie-Kate Oli- vier play two of the sisters, and Richard Olivier directs.

Act One starts in 1919 just after the Great War. The youngest daughter Carol (Julie-Kate Olivier) is having her 21st birthday party. The four Conway sisters pause to remember their late father. They also look forward to a bright future. Their favourite brother Robin (Simon Dutton) even arrives from the war in time for the game of charades. The other brother Alan (Andrew Hawkins) is already back home. Despite superficial resemblances, no- thing could be less like Chekhov's play. Priestley's way with irony is simple, but effective. Having given us the 1919 party in Act One he jumps ahead to 1938 to Kay's 40th birthday to show us what happened to these hopeful young things. There is not much left to celebrate. Financial disaster has overtaken the once prosperous family. Death and disappointment have blighted their bright aspirations. Priestley then shifts us back again to the end of the 1919 party to put its effervescent 'innocence' into perspective.

The author was much taken with theories of time. The kindly, stay-at-home brother Alan tries to comfort Kay with his insights into how time present, future and past can all be seen in one perspective if you think about it. This mystical idea seems to bring her some comfort, but it is hard to swallow. This leaves us with Priestley's resolutely middle-brow piece that sets out to show us how sad life can be. It succeeds. As he doesn't take too much trouble to investigate the characters they never really interest us; different versions of the same thing happen to them all. But Joan Plowright is not going to be put off by a little matter of undercharacterisation. She gives us a ripe, funny and self- indulgent performance as the Northern matriarch.

Previous page

Previous page