THERE IS ALWAYS THE MONEY

Robert Cottrell discovers some enticing

reasons for wanting to be the last governor of Hong Kong

Hong Kong GRANDEE WANTED. Must be of vice- regal bearing, thick-skinned, fluent in Mandarin (Whitehall and Peking dialects). Own title preferred. Five-year contract, no extension possible. Salary: high. Perks: unbelievable.

So might the small advertisement run in the Retiring Ministers' Monthly and Diplo- matic Chronicle. After five sweet-and-sour years in Hong Kong, Sir David Wilson is to depart at the tender age of 56 for London and the Lords, leaving the last great British colony to its last British master.

It is a rich, if slightly poisoned, chalice — though not, of course, that the money will come into it. (`Of course not, dear boy. It is a vast responsibility. One is sent to do the job, and one does it the best one jolly well can.') But even the most selfless of public servants will find the terms of employment a consolation for those long, hot days in Government House: they include a £135,000-a-year tax-free salary; £30,000-a-year entertainment allowance; 56 flunkeys; rent-free mansion; chauffeur- driven limousine; motor yacht; country lodge; and one of the Far East's better wine cellars.

The most efficient and popular way of awarding this last governorship would probably, in fact, be by cash auction. But assuming Downing Street sticks with its more fuddy-duddy habits of patronage, then the next master of Hong Kong is like- ly to be a former front-bencher or a crisply pressed diplomat.

Hong Kong's own business and political circles say they would prefer a politician this time round, after three successive diplomats. They believe (probably rightly) that diplomats worry too much about offending China; and (probably wrongly) that a politician would be better equipped to fight Hong Kong's corner in London. Their wish may well be granted: for even the Foreign Office itself does not now seem much inclined to defend this final fief.

For obvious reasons, the appointment will almost certainly be made after the general election, and probably not until mid-summer. On the presumption that it will remain in a Conservative govern- ment's gift, the most senior name to have been canvassed here in recent weeks is that of Sir Geoffrey Howe, who as foreign secretary was half-responsible for the terms of the 1984 Joint Declaration by which Britain agreed to return Hong Kong to China.

If Sir Geoffrey wanted the job, it would surely be his. But so far he has shown little enthusiasm — worried, perhaps, that with China showing an increasingly cavalier dis- regard for the Joint Declaration as 1997 approaches, he would risk spending most of his waking hours in Hong Kong defend- ing the merits of his own past diplomacy against its most interested critics.

Sir Geoffrey's hesitation leaves David Owen as clear current favourite — though others with their admirers in the colony include Peter Btooke (new gates for Gov- ernment House, bullet-proofing for the Rolls), John Wakeham and Lord Chal- font, with Gulf war general Sir Peter de la Billiere as a wild card. The Hong Kong 'business community', as it likes to call itself, favours somebody of the double-breasted persuasion: Dr ,Owen is its darling, closely followed by Sir Charles Powell. Yet there are moments when the 'business community' seems to be little more than an alibi for Henry Keswick, taipan of the Jardine Matheson group: and here, surely, is a man who would be at least as strong a candidate for governor in his own right, if he could only be prevailed upon to overcome his natural shyness.

Since it was Mr Keswick's great-great- great-great-uncle, William Jardine (known locally as the 'Old Iron-Headed Rat'), who almost single-handedly seized Hong Kong as a British colony in 1841, it would bring a pleasing symmetry to this chapter of colo- nial history if Mr Keswick himself were to hand the place back in 1997. True, the Iron-Headed Rat was the greatest drug baron of his age, luring tens of thousands of Chinese into opium addiction before retiring on the profits to a Scottish estate and a seat in the Commons. But if Peking would fulminate publicly against a Keswick for form's sake, it would doubtless be thrilled to bits in private by the symbolic resonance of such an appointment.

As to the consequences of a Labour elec- tion victory, Hong Kong scarcely dare think (though some suggest Gerald Kaufman, on the grounds that it would be picturesque to have an assassinated governor, just to put in the history books). In practice, the prospect of a Labour appointee would no doubt reawaken local enthusiasm for a diplomat — in which case John Boyd, Sir David Hannay and Sir Ewen Fergusson would lead the list of Foreign Office favourites.

There should not, given the available tal- ent, be much difficult for any prime minis-

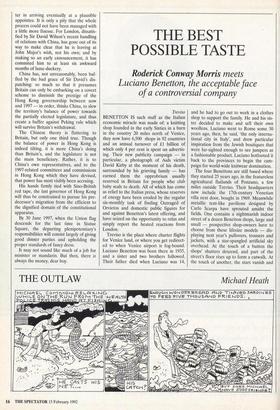

I'm giving you something to take the moment it looks as if Labour will get in.

ter in arriving eventually at a plausible appointee. It is only a pity that the whole process could not have been managed with a little more finesse. For London, dissatis- fied by Sir David Wilson's recent handling of relations with China, has gone out of its way to make clear that he is leaving at John Major's wish, not his own; and by making so an early announcement, it has commited him to at least six awkward months of lame-duckery.

China has, not unreasonably, been baf- fled by the bad grace of Sir David's dis- patching: so much so that it presumes Britain can only be embarking on a covert scheme to diminish the prestige of the Hong Kong governorship between now and 1997 — in order, thinks China, to slew the territory's balance of power towards the partially elected legislature, and thus create a buffer against Peking rule which will survive Britain's withdrawal.

The Chinese theory is flattering to Britain, but only one third true. Though the balance of power in Hong Kong is indeed tilting, it is more China's doing than Britain's, and the legislature is not the main beneficiary. Rather, it is to China's own representatives, and to the 1997-related committees and commissions in Hong Kong which they have devised, that power has most visibly been accruing.

His hands firmly tied with Sino-British red tape, the last governor of Hong Kong will thus be constrained to pursue his pre- decessor's migration from the efficient to the dignified domain of the constitutional apparatus.

By 30 June 1997, when the Union flag descends for the last time in Statue Square, the departing plenipotentiary's responsibilities will consist largely of giving good dinner parties and upholding the proper standards of fancy dress.

It may not sound like much of a job for minister or mandarin. But then, there is always the money, dear boy.

Previous page

Previous page