ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Something on their minds

James Hamilton

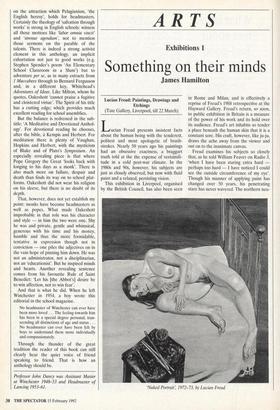

Lucian Freud: Paintings, Drawings and Etchings (Tate Gallery, Liverpool, till 22 March)

Lucian Freud presents insistent facts about the human being with the tenderest, politest and most apologetic of brush- strokes. Nearly 50 years ago his paintings had an obsessive exactness, a braggart truth told at the the expense of verisimili- tude in a cold post-war climate. In the 1980s and 90s, however, his subjects are just as closely observed, but now with fluid paint and a relaxed, persisting vision.

This exhibition in Liverpool, organised by the British Council, has also been seen in Rome and Milan, and is effectively a reprise of Freud's 1988 retrospective at the Hayward Gallery. Freud's return, so soon, to public exhibition in Britain is a measure of the power of his work and its hold over its audience. Freud's art inhabits so tender a place beneath the human skin that it is a constant sore. His craft, however, like ju-ju, draws the ache away from the viewer and out on to the inanimate canvas.

Freud examines his subjects so closely that, as he told William Feaver on Radio 3, `when I have been staring extra hard perhaps too hard — I have noticed I could see the outside circumference of my eye'. Though his manner of applying paint has changed over 50 years, his penetrating stare has never wavered. The northern neu- 'Naked Portrait; 1972-73, by LuCian Freud roses of `Girl with a Kitten' (1947), the girl apparently in the act of throttling her cat, is painted with such icy precision that the waywardness of her lower left-hand middle eyelash becomes somehow shocking. No- body has stepped inside an eyeball with such keenness as Freud, nor caught the stubborn, refractive stare that speaks of rationing and then slips evasively away. Only the cat has the nerve to return the painter's gaze.

Freud's nudes have been the most chat- tered about of his paintings, despite the fact that he came late to the nude and has woven such subjects among a large body of still lives, paintings of flowers and plants, portraits, self-portraits and figure composi- tions. The joy of his naked portraits lies in their rhythms, the sense of light, life and liquids welling up to fill sacs beneath the skin, and the rhyming repetition of breast, belly, thigh or knee. 'Naked Portrait' (1980-81) is a sleeping pregnant woman, just about to deliver, her breasts blue and red and pink and suffused with milk, her belly full, her quim ready. Freud gives us facts, for he is simply spelling out the truth, and he expects his audience to be grown-up about it too. In just the same way, in his witheringly truthful 'Wasteground with Houses, Paddington' (1970-72), Freud paints the backs of decaying terraces seen from his studio window — peeling para- pets, rusting iron cladding, unrepainted glazing bars and rubbish that would be invisible from the street starkly set in the middle of the canvas, In his naked humans, Freud shows the parts that we all really know are there, but duck; in his equally naked view of Paddington he shows us sights we all look at but prefer not to see.

His most naked, least contented portraits are those of people with all their clothes on. 'Woman in a White Shirt' (1956-57), her face traversed by rivers and ravines, a relief map of unconfided pain, seems on the point of bitter tears. 'Two Irishmen in W11' (1984-85) have something on their minds that the artist cannot discover or will not disclose. Freud's nudes, however, hum with inner contentment, despite the naked- ness of their bodies and the deliberation of their poses. Beside one, a girl curled up on a bed, is a set of artist's brushes, oil pot and paint-smudged stool, suggesting that in the end this is all a mirage, just colours pushed about in a certain way on a piece of fabric, stuff such as dreams are made on.

Although Freud may hold his sitters in a tyrannical focus, he is tougher on himself.

In 'Man with Thistle (Self Portiait)' (1946) the artist sticks his head around a shutter with a stare to break your leg, while in front of him is a dry and dangerous thistle which guards the artist like a vegetable Cerberus. The prickles rhyme with the artist's unruly hair, and his eyes wait like torpedoes. If the painting were not so com- plex, its meaning would be plain — leave me alone. In the latest self-portrait, `Reflection' (1983-85), Freud is naked, harshly lit and extraordinarily present the picture holds one down a gallery a hun- dred feet long. Herbert Read called Freud 'the Ingres of Existentialism' in the 1950s, but in the presence of his late portraits Read's epithet must be changed. Although we may be reluctant to bring out Rem- brandt as a new comparison, Freud is cer- tainly the best we have got.

Previous page

Previous page