Theatre

Night of the Iguana (Lyttelton) Faith Healer ( Royal Court)

Tropical outpouring

Christopher Edwards

The Night of the Iguana was the last major work Tennessee Williams wrote for the theatre. It was finished in 1961. No one would argue that this play ranks with his finest pieces — A Streetcar Named Desire, for instance, or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. But it possesses many of his characteristic strengths (as well as most of his usual drawbacks) and Richard Eyre and his fine cast have given it a lively revival.

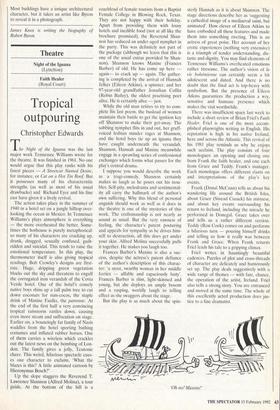

The action takes place in the summer of 1940 in a hotel set on a jungle hilltop over- looking the ocean in Mexico. In Tennessee Williams's plays atmosphere is everything — the more overheated the better. Some- times the hothouse is purely metaphorical: so many of his characters are cracking up, drunk, drugged, sexually confused, guilt- ridden and suicidal. This tends to raise the emotional temperature. In this play, the thermometer itself is also giving tropical readings. Bob Crowley's designs are first- rate. Huge, dripping green vegetation blocks out the sky and threatens to engulf the corrugated iron verandah of the Costa Verde hotel. One of the hotel's comely native boys shins up a tall palm tree to cut down coconuts for rum-cocos, the staple drink of Maxine Faulks, the patronne. At the end of the first half a very convincing tropical rainstorm rattles down, causing even more steam and suffocation on stage. Earlier on, a bouncingly fat family of Nazis waddles from the hotel sporting bathing costumes and inflated rubber horses. One of them carries a wireless which crackles out the latest news on the bombing of Lon- don. The family gives a jolly, Teutonic cheer. This weird, hilarious spectacle caus- es one character to exclaim, 'What the blazes is this? A little animated cartoon by Hieronymus Bosch?'

Up the slope staggers the Reverend T. Lawrence Shannon (Alfred Molina), a tour guide. At the bottom of the hill is a coachload of female tourists from a Baptist Female College in Blowing Rock, Texas. They are not happy with their holiday. Apart from providing them with lousy hotels and inedible food (not at all like the brochure promised), the Reverend Shan- non has seduced an under-aged nymphet in the party. This was definitely not part of the package (although we learn that this is one of the usual extras provided by Shan- non). Shannon knows Maxine (Frances Barber) of old. He has come up here again— to crack up — again. The gather- ing is completed by the arrival of Hannah Jelkes (Eileen Atkins), a spinster, and her 97-year-old grandfather Jonathan Coffin (Robin Bailey), the oldest practising poet alive. He is certainly alive — just.

While the old man retires to try to com- plete His last poem, the busload of women maintain their battle to get the ignition key off Shannon' to make their get-away. The sobbing nymphet flits in and out, her gruff- voiced lesbian minder rages at Shannon, and the hotel boys tie up an iguana they have caught underneath the verandah. Shannon, Hannah and Maxine meanwhile engage in a sprawling series of confessional exchanges which forms what passes for the play's central drama.

I suppose you would describe the work as a tragi-comedy. Shannon certainly makes us laugh as he pours out his trou- bles. Self-pity, melodrama and sentimental- ity all carry the hallmark of the author's own suffering. Why this blend of personal anguish should work as well as it does in the theatre is one of the mysteries of this work. The craftsmanship is not nearly as sound as usual. But the very rawness of feeling, the character's patent posturing and appeals for sympathy as he drives him- self to destruction, all this does get under your skin. Alfred Molina successfully pulls it together. He makes you laugh too.

Frances Barber's Maxine is also a suc- cess, despite the actress's patent defiance of the author's description of this charac- ter: 'a stout, swarthy woman in her middle forties — affable and rapaciously lusty'. Frances Barber is slim, light-skinned and young, but she deploys an ample bosom and a rasping, worldly laugh to telling effect as she swaggers about the stage.

But the play is as much about the spin- sterly Hannah as it is about Shannon. The stage directions describe her as 'suggesting a cathedral image of a mediaeval saint, but animated'. How clever of Eileen Atkins to have embodied all these features and made them into something riveting. This is an actress of great poise. Her account of her erotic experiences (nothing very extensive) is a triumph of tender understanding, dis- taste and dignity. You may find elements of Tennessee Williams's overheated emotions rather tiresome. The author's vision of la vie bohemienne can certainly seem a bit adolescent and dated. And there is no doubt that the final act is top-heavy with symbolism. But the presence of Eileen Atkins guarantees the production a wry, sensitive and humane presence which makes the visit worthwhile.

There was insufficient space last week to include a short review of Brian Friel's Faith Healer. Friel is one of the most accom- plished playwrights writing in English. I I is reputation is high in his native Ireland, here and across the Atlantic. This revival of his 1981 play reminds us why he enjoys such acclaim. The play consists of four monologues: an opening and closing one from Frank the faith healer, and one each from Grace and Teddy, Frank's manager. Each monologue offers different slants on and interpretations of the play's key events.

Frank (Donal McCann) tells us about his wandering life around the British Isles, about Grace (Sinead Cusack) his mistress, and about key events surrounding his return to Ireland, including the miracle he performed in Donegal. Grace takes over and tells us a rather different version. Teddy (Ron Cook) comes on and performs a hilarious turn — pouring himself drinks and telling us how it really was between Frank and Grace. When Frank returns Friel leads his talc to a gripping climax.

Friel writes in hauntingly beautiful cadences. Puzzles of plot and cross-threads of character are delicately and humorously set up. The play deals suggestively with a wide range of themes — with fate, chance, the operation of the artist, Ireland. Friel also tells a strong story. You are entranced and moved at the same time. The whole of this excellently acted production does jus- tice to a fine dramatist.

'Oh no! Masons!'

Previous page

Previous page