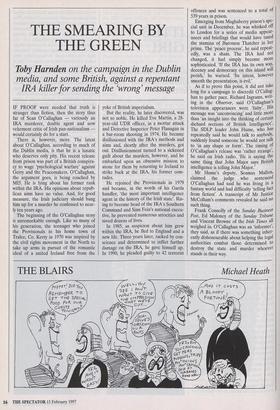

THE SMEARING BY THE GREEN

Toby Harnden on the campaign in the Dublin

media, and some British, against a repentant

IRA killer for sending the 'wrong' message IF PROOF were needed that truth is stranger than fiction, then the story thus far of Sean O'Callaghan — variously an IRA murderer, double agent and now vehement critic of Irish pan-nationalism would certainly do for a start.

There is, however, more. The latest about O'Callaghan, according to much of the Dublin media, is that he is a lunatic who deserves only pity. His recent release from prison was part of a British conspira- cy to wage 'psychological warfare' against Gerry and the Peacemakers. O'Callaghan, the argument goes, is being coached by MI5. He is lying about his former rank within the IRA. His opinions about repub- lican aims have no value. And, for good measure, the Irish judiciary should bang him up for a murder he confessed to near- ly ten years ago.

The beginning of the O'Callaghan story is unremarkable enough. Like so many of his generation, the teenager who joined the Provisionals in his home town of Tralee, Co. Kerry in 1970 was inspired by the civil rights movement in the North to take up arms in pursuit of the romantic ideal of a united Ireland free from the yoke of British imperialism.

But the reality, he later discovered, was not so noble. He killed Eve Martin, a 28- year-old UDR officer, in a mortar attack and Detective Inspector Peter Flanagan in a bar-room shooting in 1974. He became disillusioned with the IRA's methods and aims and, shortly after the murders, got out. Disillusionment turned to a sickened guilt about the murders, however, and he embarked upon an obsessive mission to atone for them by returning to Ireland to strike back at the IRA, his former com- rades.

He rejoined the Provisionals in 1979 and became, in the words of his Garda handler, 'the most important intelligence agent in the history of the Irish state'. Ris- ing to become head of the IRA's Southern Command and Sinn Fein's national execu- tive, he prevented numerous atrocities and saved dozens of lives.

In 1985, as suspicion about him grew within the IRA, he fled to England and a new life. Three years later, racked by con- science and determined to inflict further damage on the IRA, he gave himself up. In 1990, he pleaded guilty to 42 terrorist offences and was sentenced to a total of 539 years in prison.

Emerging from Maghaberry prison's spe- cial unit in December, he was whisked off to London for a series of media appear- ances and briefings that would have taxed the stamina of Baroness Thatcher in her prime. The 'peace process', he said repeat- edly, was a sham. The IRA had not changed, it had simply become more sophisticated. 'If the IRA has its own way, decency and democracy on this island will perish,' he warned. 'Its intent, however smooth the presentation, is evil.' As if to prove this point, it did not take long for a campaign to discredit O'Callag- han to gather pace. Richard Ingrams, writ- ing in the Observer, said O'Callaghan's television appearances were 'fishy'. His message was 'unconvincing' and little more than 'an insight into the thinking of certain diehard sections of British Intelligence'. The SDLP leader John Hume, who has repeatedly said he would talk to anybody, suddenly found someone he would not talk to 'in any shape or form'. The timing of O'Callaghan's release was 'rather strange', he said on Irish radio. 'He is saying the same thing that John Major says British intelligence is telling John Major.'

Mr Hume's deputy, Seamus Mallon, claimed the judge who sentenced O'Callaghan had said he was living in a fantasy world and had difficulty 'telling fact from fiction'. A transcript of Mr Justice McCollum's comments revealed he said no such thing.

Frank Connolly of the Sunday Business Post, Ed Maloney of the Sunday Tribune and Vincent Browne of the Irish Times all weighed in. O'Callaghan was an 'informer', they said, as if there was something inher- ently dishonourable about helping the legal authorities combat those determined to destroy the state and murder whoever stands in their way. This coterie made much of the murder of John Corcoran, another informer. O'Callaghan confessed to the killing when he gave himself up in 1988, but as he already faced a multitude of charges the Irish Director of Public Prosecutions decided not to take action. O'Callaghan says he tried to warn his Garda handlers when he was ordered to execute' Corcoran. The police never came, and Corcoran's trussed and hooded body was later found in a field. He had been shot in the head. The death of Corco- ran, an epileptic father of eight, is not a source of pride for O'Callaghan. A pathet- ic, helpless man, his murder seems to sum up the murky, duplicitous world in which O'Callaghan operated. For O'Callag-han to have spared Corcoran would have been to sign his own death warrant. Perhaps the Garda handlers calculated that Corcoran's life was not worth the risk of compromis- ing their most important agent. The attacks on O'Callaghan, however, are becoming a little threadbare. Garret Fitzgerald, the former Taoiseach, has con- firmed he was told in 1983 how O'Callag- han had managed to foil an IRA plot to murder the Prince and Princess of Wales at a pop concert. 'Republican sources' had previously pooh-poohed O'Callaghan's claims about this. Even more telling was the reaction to O'Callaghan's revelation that he and Gerry Adams had discussed killing John Hume in 1982. 'I have never heard of any republicans, even in jest and even in the difficult periods that have been behind us, discussing any sort of punitive action against John Hume,' said Mr Adams. Furthermore, he added, he had never heard republicans discussing 'punitive action' (translation: murder) against Ian Paisley. Can Mr Adams really have been telling the truth? Mr Paisley has survived at least two attempts on his life. It was an uncharacteristic slip. The existence of a detailed plan to murder Mr Hume, more- over, was subsequently confirmed by IRA members who spoke to Suzanne Breen of the Irish Times, a journalist not known for her links with British military intelligence.

Much to the chagrin of Mr Adams, Mr Hume and many in the Irish media, O'Callaghan is to be granted an American visa. He will travel to the United States to warn of the dangers of the romantic Irish nationalism that took him, as a rebellious teenager, from the fields of Kerry to mur- der on the streets of Northern Ireland.

Paradoxically, it is O'Callaghan's terror- ist past that makes his voice such a power- ful antidote to terrorism present. The chances of his one day being murdered by the IRA are probably even. Or perhaps the smears and innuendos will be judged sufficient to neutralise him. Whatever its eventual ending, the story of Sean O'Callaghan is not over yet.

The author is based in Belfast as the Irish correspondent of the Daily Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page