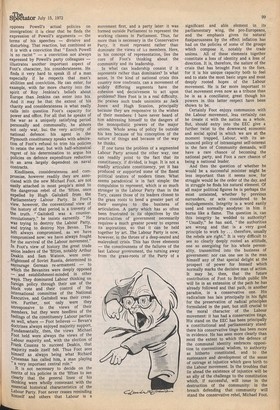

Profile

The conservative rebel

Patrick Cosgrave

There can be no doubt, that, since the last general election, Michael Foot has moved into a new, and totally unexpected, phase of his career. It is unexpected in three ways: first, in that a great political rebel was seduced, not by the joys of office, but by the responsibilities of opposition; second, in that Foot moved on to his party's front bench at all; third, in that he did so without losing his hold on the affections and support of the Parliamentary left wing in which he has been for so long a dominant figure. "He is no Marxist," a left-wing admirer who considers himself such told me recently. "Perhaps he is not even a socialist. But he is the foremost figure on the left." Agreeing with that analysis, another parliamentary colleague added: "Michael is now the only hope of saving the Labour Party. Unlike Harold he has not been discredited. Unlike Roy he is not a wrecker. And he sees his responsibilities at last."

Yet, pressed, few can say with confidence what Foot stands for, or even against. Certainly, he was for CND; certainly he is against the Common Market: but it is difficult to identify him with any schematic system of policy. I was to lunch with him the other day and, when he was late in arriving, I assumed he had been held up at the press conference held to launch the Labour Party's new policy document. When he limped into the room and apologised with habitual grace I mentioned this assumption and was surprised to find that he had no idea that there was a press conference that day; and he seemed, if not indifferent to, nonetheless vague about, the policy document itself. Yet he is not unconcerned with detail: the ardour and assiduity with which he has fought to foster the steel industry in his constituency, and the meticulous concern with the often tiny facts that go to make up his continuous arguments on the subject — as well as his mastery of them — disprove any such charge.

Perhaps the clue lies in an answer he recently gave to an interviewer who taxed him with the proposition that his constituents would be happier and more prosperous away from Ebbw Vale, and that the advocacy of such a redistribution of population made better socialism than his own attempts to save an existing, but struggling, community. "I don't say this is perfect socialism," he replied of his efforts: but his people wanted to stay where they were, and it was his job to see that they did so in such prosperity and comfort as could be achieved. Likewise, the time in his own life when he was happiest was during the war. Then " Britain " — and the emphasis on the national noun is sharp in all his utterances — had a common life and purpose; there were more people happier at that moment than at any time in our history; and this was what made the existence of a community worthwhile — this was his definition of what socialism was all about. The sense of communal and national identity is a very strong force in Foot. Within it his understanding of the greatest good of the greatest number is in no way Benthamite or materialist: struggle is acceptable, el.ien welcome, provided only that all share in.it, and that a privileged elite is not excepted from the communal effort — only in his desire to destroy economic elites with the apparatus of socialist thinking, like nationalisation, is he a true believer in the intellectual creed to which he casually subscribes. He seeks no eventual pinnacle on which all may rest in comfort: he requires only that the effort which life demands in a political society be justly and equally distributed and rewarded.

It is an unusually stringent, and unusually moral, view of politics. Commonly, it has been considered one that divorced Foot from power, and left him permanently outside government, as the tribune of the moral conscience of the Labour Party. But, questioned on he subject of electoral politics, Foot argues strenuously that the Labour Party can win the next election, and adds, simply but with force, "I am interested in winning." Certainly, when he speaks in public his language is not merely that of struggle and denunciation;, but of defeat and victory.

Yet he constantly treats office with suspicion. After Harold Wilson had a "hypothetical and tentative" conversation with him on the subject during the 1964 parliament, he wrote to the Prime Minister to say that British policy on Vietnam made his entry into the government impossible: was produced; and the hints of a job for Michael Foot were heard no more. But, in any event, the bugbear of Vietnam remained; and to it was added the bugbear of the Labour government's incomes policy.

The question of whether he would have accepted office even without these obstacles is open to doubt, for when the prospect of his standing for the Deputy Leadership of his party arose he required much persuasion — and a stern emphasis on his duty — before he put himself forward. I put this down less to any intellectual stand-offishness of the kind so often found on the left, than to an inherent diffidence of character, oddly in contrast to his trenchant oratory. When I first heard Foot speak in the House of Commons — in the debate on American intervention in Cambodia in 1969 — I was for several minutes puzzled and disappointed by the slowness, and the halting character, of his delivery: the expected thunder failed to roll, the expected lightning to strike. Slowly, like a recalcitrant but genuinely powerful engine, he warmed up. The gestures, though they remained jerky, encompassed more space; the flow of words became, first smooth, then passionate, then eloquent. The power and force of his character filled the chamber; and, when he sat down, one had experienced something remarkable. Likewise, in conversation, there is an initial hesitancy, an opening shyness until, sensing his companions, and warming to his themes, the humour, the passion and the charm all make themselves felt.

He thinks through his emotions. It is this, in the conventional wisdom, that creates the greatest apparent disjunction between his sense of community — his, self-called, primitive socialism — and his as yet untested capacity for power. This is. what I — we — feel, he seems to say: this, therefore, is what we must struggle for. What is just, rather than what is possible, or advantageous, governs his thinking. There is a subtle, but very real difference here between his approach to politics and that of another rebel orator with whom he is increasingly compared, Enoch Powell. This is what is real, Powell says: what is real limits what we can achieve; our purpose is merely to maximise freedom within the limits of reality. Powell's rationalism exists alongside his passion. Foot's is merged with his. Yet both — as their alliance on the question of House of Lords reform and on the European Communities Bill demonstrate — share a common passion as parliamentarians and constitutionalists. In the institution of Parliament their common sense of community finds its apotheosis, and Foot speaks with, if possible, deeper admiration for Powell than Powell for Foot, describing one of his recent speeches as "majestic," calling him the only really powerful intellect on the Tory side of the House, and insisting on the silliness of those on the left who see in Powell some kind of dangerous revolutionary. Yet, asked about Powell's views on immigration, Foot's face creases in worry and concern and he mutters that the immigration speeches are aberrant.

It is not clear to me to what extent Foot Opposes Powell's actual policies on immigration: it is clear that he finds the expression of Powell's arguments — the terms of his speeches — divisive and disturbing. That reaction, but combined as it is with a conviction that "Enoch Powell is no racist" — a conviction not always expressed by Powell's party colleagues — illustrates another important aspect of Foot's character, his considerateness. He finds it very hard to speak ill of a man especially if he respects that man's abilities and conviction. He can enter, for example, with far more charity into the spirit of Roy Jenkins's beliefs about Europe than Jenkins can enter into his. And it may be that the extent of his charity and considerateness is what really calls into question Foot's capacity for power and office. For all that he speaks of the war as a uniquely satisfying period personally and communally, he abhors not only war, buL the very activity of national defence: his agent in the Plymouth constituency speaks with admiration of Foot's refusal to trim his policies to retain the seat; but with half-whimsical regret of his determination to argue his policies on defence expenditure reduction in an area largely dependent on naval contracts.

Kindliness, considerateness and compromise, however readily they are associated with the new Michael Foot, are not easily attached in most people's mind to the dangerous rebel of the 'fifties, once expelled by Hugh Gaitskell from the Parliamentary Labour Party. In Foot's view, however, the conventional view of the history of that period is a travesty of the truth. " Gaitskell was a counterrevolutionary," he insists earnestly. "He Was trying to destroy the Labour Party, and trying to destroy Nye Bevan. The left always compromised, as we have compromised now: we have always fought for the survival of the Labour movement." In Foot's view of history the great trade union leaders of the 'fifties, notably Arthur Deakin and Sam Watson, were over,. frightened of Soviet Russia, determined to encourage German re-armament — to Which the Bevanites were deeply opposed — and establishment-minded in other ways. They dominated Labour thinking on foreign policy through their use of the block vote and their control of the international committee of the National Executive, and Gaitskell was their creature. Further, not only were they unresponsive to the views of their members, but they were heedless of the feelings of the constituency Labour parties as well, where — Foot believes — Bevan's doctrines always enjoyed majority support. Fundamentally, then, the views Michael Foot held were always the views of the Labour majority and, with the election of Frank Cousins to succeed Deakin, that majority made itself felt. Thus Foot sees himself as always being what Richard Crossman has called him, a man playing " a very important central role."

It is not necessary to decide on the merits of his policies in the 'fifties to see Clearly that the general lines of his thinking were wholly consonant with the essential historical characteristics of the Labour Party. Foot never ceases reminding himself and others that Labour is a

movement first, and a party later: it was formed outside Parliament to represent the working classes in Parliament. Thus, far more than is necessary in the Conservative Party, it must represent rather than dominate the views of i Ls members. Here, in his concept of representation, lies the core of Foot's thinking about the community and its leadership.

In what can leadership consist if it represents rather than dominates? In what sense, in the kind of national crisis this country now confronts, can a movement of widely differing segments have the cohesion and decisiveness to act upon problems? Here Foot is in a real difficulty. He praises such trade unionists as Jack Jones and Hugh Scanlon, principally because they are responsive to the wishes of their members: I have never heard of him addressing himself to the dangers of the monopolistic powers of the major unions. Whole areas of policy lie outside his ken because of his conception of the nature of things and because of the way he thinks.

If one turns the problem of a segmented Labour Party around the other way, one can readily point to the fact that its constituency, if divided, is huge. It is not a readily articulate constituency, yet it has produced or supported some of the finest political orators of modern times. What seems paradoxical is in fact simple: the compulsion to represent, which is so much stronger in the Labour Party than in the Tory, causes those of its leaders closest to the grass roots to bend a greater part of their energies to the business of articulation. A party which has so often been frustrated in its objectives by the practicalities of government necessarily requires a much greater power to express its aspirations, so that it can be held together by art. The Labour Party is now, however, in the throes of a deep-seated and malevolent crisis. This has three elements — the consciousness of the failures of the last Labour government, the turning away from the grass-roots of the Party of a

significant and able element in its parliamentary wing, the pro-Europeans, and the emphasis given its natural fissiparousness by the effect inflation has had on the policies of some of the groups which compose it, notably the trade unions. All of these elements together • constitute a loss of identity and a loss of direction. It is, therefore, the nature of the crisis that has brought Foot to the fore, for it is his unique capacity both to feel and to state the most basic urges and most deeply rooted hopes of the Labour movement. He is far more important to that movement even now as a tribune than he is as a conciliator, great though his powers in this latter respect have been shown to be.

Certainly Foot enjoys communion with the Labour movement, less certainly can he create it with the nation as a whole. But, should entry into the EEC give a further twist to the downward economic and social spiral in which we are at the moment trapped, Labour, with its announced policy of intransigent self-interest in the face of Community demands, will have a rare chance of becoming the national party, and Foot a rare chance of being a national leader.

And then the question of whether he would be a successful minister might be less important than it seems now, for struggle would be the order of the day, and in struggle he finds his natural element. Of all major political figures he is perhaps the most untainted, whether by previous surrenders, or acts considered to be misjudgements. Integrity is a word easily used and normally anodyne: in him it burns like a flame. The question is, can this integrity be wedded to authority? " Usually," he has said, "the authorities are wrong and that is a very good principle to work by ... therefore, usually the rebels are right." It is very difficult to see so clearly deeply rooted an attitude, one so energising for his whole personality, transmitted into the business of government: nor can one see in the man himself any of that special delight at the prospect of power for himself which normally marks the decisive man of action. It may be, then, that the future contribution of Foot to British public life will lie in an extension of the path he has already followed and that path, in another paradox, is a conservative one. His radicalism has lain principally in his fight for the preservation of radical principles formulated in the past, but still crucial to the moral character of the Labour movement: it has had a conservative tinge. His stand on the EEC has been principally a constitutional and parliamentary stand: there his conservative tinge has been more in evidence. He has seen more clearly than most the extent to which the defence of the communal identity embraces opposition to conventional wisdom, to authority as hitherto constituted, and to the sustenance and development of the sense of outrage at injustice which gave birth to the Labour movement. In the troubles that lie ahead the existence of injustice will be an ally of the challenge to the constitution which, if successful, will issue in the destruction of the community: in the breach defending that community will stand the conservative rebel, Michael Foot.

Previous page

Previous page