Exhibitions 2

Treasures from Abbot Hall (Leger Galleries, till 4 August)

Cumbrian oasis

Celina Fox

0 ne of the dangers of living in a time of government cutbacks for the arts is the tendency to compare the present state of affairs with a past golden age when culture supposedly flourished in Britain. The con- trast is illusory. I grew up in the town of Kendal, Westmorland (now Cumbria, emphatically not Cumberland, pace The Spectator's July Arts Diary), which was in the Fifties a cultural desert, offering little but an annual music festival to slake the thirst between Manchester and Edinburgh. Yet today it has a thriving arts centre converted from the local brewery, a custom-built concert hall in the leisure centre and an art gallery/museum — in- stitutions that would stand comparison with those in any German town of compa- rable size.

The initiative for these developments did not come from government agencies, but from the collective effort of civically minded individuals in the region. One of their success stories is the Abbot Hall Art Gallery, housed alongside the river Kent next to the parish church in a fine Georgian mansion which used to be my nursery school. I cannot claim to have been alert then to the condition of the ceiling mould- ings or the roof slates, but evidently it was during my tenure that the building fell into such disrepair that demolition was contem- plated.

The Hall dates back to the mid-18th century when Kendal was one of the most flourishing towns in the North, its inhabi- tants having diversified beyond the staple trade in wool to manufacture everything from snuff to horn and leather goods. The town had a grammar school, theatre, coffee-house and news-sheet; it was well connected by turnpike across the fells to Yorkshire and down south to London. The house was built for the son of a local MP, possibly to the design of Carr of York, and it continued to serve as a residence for the local minor gentry and professional classes until it was sold at the end of the last century to Kendal Corporation.

For years there were vague plans to turn the Hall into a centre for the arts, but only when threatened by subsidence, dry rot and woodworm was a trust formed to raise funds for its restoration and conversion. With the help of the local Provincial Insurance Company and associated family trusts, these aims were realised. Nor was it simply a hollow architectural shell when it opened in 1962. Unusually for an English town, Kendal could boast an 18th-century `school' of artists. Christopher Steele, George Romney and Daniel Gardner were all born in the area and patronised by its society, while furniture of a metropolitan sophistication was being produced by Gil- lows of Lancaster, 25 miles away. At Leger's show (13 Old Bond Street, W1) we can see how this aesthetic core has been capitalised upon through the energetic tapping of public and private funds, as well as through generous gifts and be- quests.

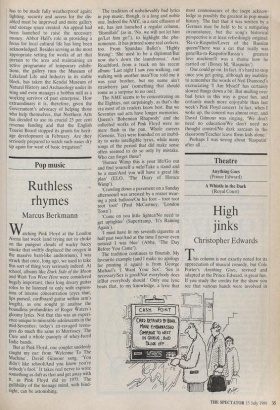

Georgian provincial artists were not so stuck in a stylistic backwater as might be supposed. In her highly informative cata- logue, the gallery's present curator Vicky Slowe points out that Christopher Steele studied for a year in Paris with Vanloo, returning home dressed in the height of French fashion to the amazement of the locals. His pupil Romney travelled exten- sively in Italy during the 1770s and was as `The Gower Family', by George Romney thoroughly imbued with the ideals of neo- classicism as any French academician. Gardner studied at the Royal Academy schools and could be found in Paris during the brief interlude between the Revolu- tionary and Napoleonic wars. On display we can see charming portraits of local bigwigs decked out in all their finery, but also the magnificent Romney portrait of `The Gower Family' — the eldest, Lady Anne, languidly strumming a tambourine to her young step-siblings' ring o'roses — a brilliantly successful reworking of classical compositional rhythms and imagery. This arcadian mood darkens into the troubled romanticism of the artist's group portrait, `The Four Friends', painted some 20 years later, and his apocalyptic prison scene deep-toned in pen and wash, nominally representing the visit of the reformer John Howard to a lazaretto.

The natural beauty of the gallery's en- virons has provided another point of refer- ence for its choice of acquisitions. Gard- ner's friendship with the young Constable was the catalyst for the latter's visit to the Lake District, and a pencil sketch he made of the cascade at Rydal Hall is included in the show. J. R. Cozens's watercolour of Lodore falls — one of only two Lakeland scenes that can be attributed with certainty to the artist — and views of Langdale by William Havel! and Edward Lear recall other highlights of the picturesque tour. But the most impressive rendering of the region's attractions are the two large oils of Belle Isle, Windermere, painted by P. J. de Loutherbourg, which hung in situ on the island in John Plaw's idiosyncratic round house until transferred by private treaty sale (and with the help of Bowness Bay Boat Company) to Abbot Hall last year. Anyone familiar with this frankly tame part of the Lakes will be astonished by the artist's spirited vision of 'Belle Isle in a Storm' — evidently inspired by the folk memory of a wedding party drowned while attempting the crossing — here invested with all the dramatic scale of a shipwreck in the Atlantic. In contrast, 'Belle Isle in a Calm' takes on the complexion of a Clau- dian pastoral, with local farmers trans- formed into Italian peasants and the gentry rowed across to the island in idyllic repose. The gallery is fortunate to have been given an extensive collection of drawings by Ruskin, whose watercolour impressions of the Alps in different weather conditions and meticulous studies of rocks and flora are among the finest works in the exhibi- tion. Nor is the present century excluded. All three curators responsible for Abbot Hall since its foundation have made mod- ern acquisitions, notably collages by the North German exponent of Dada, Kurt Schwitters, who settled in Ambleside after the war, as well as works by contemporary British painters, sculptors and potters.

The point of bringing these treasures to London is not, needless to say, simply to attract additional publicity. The building has to be made fully weatherproof again; lighting, security and access for the dis- abled must be improved and more gallery and storage space created. An appeal had been launched to raise the necessary money. Abbot Hall's role in providing a focus for local cultural life has long been acknowledged. Besides serving as the most appropriate setting for works of art that pertain to the area and maintaining an active programme of temporary exhibi- tions, the gallery runs the Museum of Lakeland Life and Industry in its stable block, has taken the Kendal Museum of Natural History and Archaeology under its wing and even manages a bobbin mill as a working survivor of past enterprise. How extraordinary it is, therefore, given the Government's advocacy of helping those who help themselves, that Northern Arts has decided to axe its crucial 25 per cent revenue funding and that the English Tourist Board stopped its grants for herit- age development in February. Are they seriously prepared to watch such oases dry up again for want of basic irrigation?

Previous page

Previous page