The Spectator, 56 Doughty Street, London WC1N 2LL Telephone 01-405

1706; Tekx 27124; Fax 242 0603

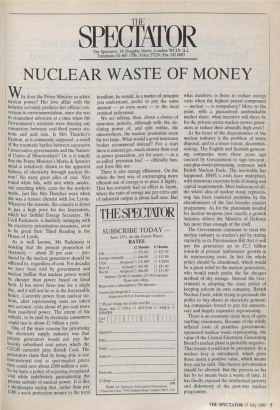

NUCLEAR WASTE OF MONEY

Wby does the Prime Minister so adore nuclear power? Her love affair with the industry certainly predates her official con- version to environmentalism, since she was its staunchest advocate at a time when the Government's scientists were denying any connection between coal-fired power sta- tions and acid rain. Is Mrs Thatcher's fixation, as is commonly supposed, a result of the traumatic battles between successive Conservative governments and the Nation- al Union of Mineworkers? Or is it simply that the Prime Minister's Marks & Spencer mind is intuitively drawn to the apparent tidiness of electricity through nuclear fis- sion? No nasty great piles of coal. Nice round white lids, with nice white smoke, and matching white coats for the workers inside, just like Mrs Thatcher wore when she was a trainee chemist with Joe Lyons. Whatever the reasons, this country is about to pay a high price for her fascination, which her faithful Energy Secretary, Mr Cecil Parkinson, is dutifully indulging with his electricity privatisation measures, soon to be given their Third Reading in the House of Lords.

As is well known, Mr Parkinson is insisting that the present proportion of electricity — about 20 per cent — pro- duced by the nuclear generators should be adhered to, regardless of cost. For decades We have been told by government and nuclear boffins that nuclear power would be cheaper than power based on fossil fuels. It has never been true for a single day, and it will not be so in the foreseeable future. Currently power from nuclear sta- tions, after reprocessing costs are taken into account, costs about 45 per cent more than coal-fired power. The extent of the subsidy, to be paid by electricity consumers, 'could run to about £1 billion a year.

One of the main reasons for privatising the electricity supply industry was that Private generators would not pay the heavily subsidised coal prices which the CEGB currently pays British Coal. The generators claim that by being able to .use international coal at spot-market prices they could save about £500 million a year. So we have a policy of rejecting overpriced coal while indefinitely guaranteeing the greater subsidy of nuclear power. It is like a shopkeeper saying that, rather than pay £100 a week protection money to the local

hoodlum, he would, as a matter of principle you understand, prefer to pay the same amount — or even more — to the local crooked policeman.

We are talking, then, about a choice of insurance policies, although with the de- clining power of, and split within, the mineworkers, the nuclear premiums seem far too large. What would a good insurance broker recommend instead? For a start there is natural gas, much cleaner than coal in power generation, yet for years — as a so-called 'premium fuel' — officially ban- ned from this use.

There is also energy efficiency. On the whole the best way of encouraging more efficient use of energy is to price it highly. That has certainty had an effect in Japan, where the ratio of energy use per extra unit of industrial output is about half ours. But

what incentive is there to reduce energy costs when the highest priced component — nuclear — is compulsory? More to the point, with a guaranteed unshrinkable market share, what incentive will there be for the private sector nuclear power gener- ators to reduce their absurdly high costs?

At the heart of the diseconomies of the nuclear industry is the problem of waste disposal, and to a lesser extent, decommis- sioning. The English and Scottish generat- ing companies were three years ago coerced by Government to sign ten-year, cost-plus-waste-processing contracts with British Nuclear Fuels. The inevitable has happened. BNFL's costs have multiplied, with enormous overruns both of timing and capital requirements. Most ludicrous of all, the whole idea of nuclear waste reproces- sing has been rendered pointless by the abandonment of the fast breeder reactor programme. As for the plutonium needed for nuclear weapons (not exactly a growth business either) the Ministry of Defence has more than enough of the stuff.

The Government continues to treat the nuclear industry as teacher's pet by stating explicitly in its Privatisation Bill that it will pay the generators up to £2.5 billion towards at present 'unforeseen' growth in its reprocessing costs. In fact the whole policy should be abandoned, which would be a great relief to the nuclear generators, who would much prefer the far cheaper method of dry storage. Instead the Gov- ernment is adopting the crazy policy of keeping solvent its own company, British Nuclear Fuels, while trying to persuade the public to buy shares in electricity generat- ing companies forced to pay for unneces- sary and hugely expensive reprocessing.

There is an economic circle here of quite startling viciousness. Because of the wildly inflated costs of pointless government- sponsored nuclear waste reprocessing, the value of the Central Electricity Generating Board's nuclear plant is probably negative. That means it could not be privatised. So a nuclear levy is introduced, which gives those assets a positive value, which means they can be sold. This bizarre privatisation should be aborted. But the process so far has by no means been a waste of time. It has finally exposed the intellectual poverty and dishonesty of the post-war nuclear programme,

Previous page

Previous page