VERY LIBERAL NOVELIST

Survivors: A profile of Sir Angus Wilson, tireless innovator

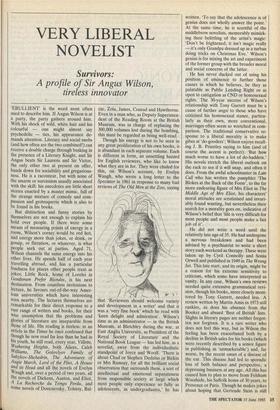

'EBULLIENT' is the word most often used to describe him. If Angus Wilson is at a party, the party gathers around him. With his shock of wild, white hair and his colourful — one might almost say psychedelic — ties, his appearance de- mands attention. Literary and social snobs (and how often are the two combined!) can receive a double charge through basking in the presence of a Literary Knight, and Sir Angus beats Sir Laurens and Sir Victor, the only other two at present on offer, hands down for sociability and gregarious- ness. He is a raconteur, but with none of the smarm or narcissism usually associated with the skill: his anecdotes are little short stories enacted by a master mimic, full of the strange mixture of comedy and com- passion and grotesquerie which is also to be found in his books.

But distinction and funny stories by themselves are not enough to explain his hold over people. If there were some means of measuring points of energy in a room, Wilson's corner would be red hot, and energy more than jokes, or drink, or gossip, or flirtation, or whatever, is what People seek out at parties. Aged 71, Wilson channels the same energy into his Other lives. He spends half of each year travelling abroad, and has a particular fondness for places other people treat as Jokes: Little Rock, home of Lorelei in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, is his next destination. From countless invitations to lecture, he favours out-of-the-way Amer- man universities which have interesting ZOOS nearby. The lectures themselves are • remarkable for their direct response to a vast range of writers and books, for their wise assumption that the problems and glories of literature are inseparable from those of life. His reading is tireless: in an article in the Times he once confessed that though he now read far less than he had in his youth, he still read, every year, Villette, Wuthering Heights, both Alices, Caleb Williams, The Golovlyov Family of Saltykov-Shchedrin, The Adventures of Augie March, Lord of the Flies, A House and its Head and all the novels of Evelyn Waugh and, over a period of two years, all the novels of Dickens, Austen, and Eliot, A La Recherche du Temps Perdu, and some novels of Dostoievsky, Tolstoy, Bal- zac, Zola, James, Conrad and Hawthorne. Even in a man who, as Deputy Superinten- dent of the Reading Room at the British Museum, was in charge of replacing the 300,000 volumes lost during the bombing, this must be regarded as being well-read.

Though his energy is not to be seen in any great proliferation of his own books, it is abundant in each separate volume. Each is different in form, an unsettling hazard for English reviewers, who like to know what they are in for. They were chided for this, on Wilson's account, by Evelyn Waugh, who wrote a long letter to the Spectator in 1961 in response to many bad reviews of The Old Men at the Zoo, saying that 'Reviewers should welcome variety and development in a writer' and that it was a 'very fine book' which he read with 'keen delight and admiration'. Wilson's time as an administrator — in the British Museum, at Bletchley during the war, at East Anglia University, as President of the Royal Society of Literature and the National Book League — has led him, as a novelist, away from the individualistic standpoint of Joyce and Woolf. 'There is about Chad or Stephen Dedalus or Birkin or Mrs Ramsay, for all the brilliant social observation that surrounds them, a sort of intellectual and emotional separateness from responsible society at large which most people only experience so fully as adolescents, as undergraduates,' he has written. 'To say that the adolescence is of genius does not wholly answer the point.'

At the same time, he is scornful of the middlebrow novelists, memorably mimick- ing their belittling of the artist's magic: 'Don't be frightened, it isn't magic really — it's only Grandpa dressed up in a turban doing tricks on Christmas Eve.' Wilson's genius is for mixing the art and experiment of the former group with the broader moral and social concerns of the latter.

He has never ducked out of using his position of eminence to further those causes in which he believes, be they as palatable as Public Lending Right or as open to castigation as CND or homosexual rights. The 30-year success of Wilson's relationship with Tony Garrett must be a cause of further angst to those who have criticised his homosexual stance, particu- larly as their own, more conventional, marriages often seem so wretched in com- parison. The traditional conservative re- sponse to a liberal morality is to make gibes at `do-gooders'; Wilson enjoys recall- ing J. B. Priestley saying to him (and of course the accent is perfect): 'But how much worse to have a lot of do-badders.' His novels stretch the liberal outlook on the rack to see if it will snap, and often it does. From the awful schoolmaster in Late Call who has written the pamphlet 'The Blokes at the Back of the Form', to the far more endearing figure of Mrs Eliot in The Middle Age of Mrs Eliot, his characters' moral attitudes are scrutinised and invari- ably found wanting, but nevertheless their search for a morality goes on, indicative of Wilson's belief that 'life is very difficult for most people and most people make a fair job of it'.

He did not write a word until the relatively late age of 35. He had undergone a nervous breakdown and had been advised by a psychiatrist to write a short story each weekend as therapy. These were taken up by Cyril Connolly and Sonia Orwell and published in 1949 in The Wrong Set. This late start, and its origin, might be a reason for his extreme sensitivity to criticism, which some have interpreted as vanity. In any case, Wilson's own reviews needed quite extensive grammatical revi- sion, though his books, more closely moni- tored by Tony Garrett, needed less. A review written by Martin Amis in 1973 still rankles, as does his absence from the Booker and absurd 'Best of British' lists. Slights in literary pages are neither forgot- ten nor forgiven. It is a rare writer who does not feel this way, but in Wilson the feeling has been exacerbated both by a decline in British sales for his books (which were recently described by a senior figure in publishing as 'unmarketable') and, far worse, by the recent onset of a disease of the ear. This disease had led to sporadic loss of both balance and perspective, a depressing business at any age. All this has caused him to plan to move from Felsham Woodside, his Suffolk home of 30 years, to Provence or Paris. Though he makes jokes about hoping that Gertrude Stein is still there to greet him, his sadness is evident.

A linguist and a lover of café society, Angus Wilson is bound to survive his self-imposed exile. But what of Britain without him? No more the bright ties and the shock of hair, no more the jokes and the stories of his bizarre family (his gamb- ler father on bullfighting: 'Blood every- where! Never laughed so much in m'life!'), no more the generous encouragement of younger English writers (McEwan, Farrell, Drabble, etc, etc), no more the do-gooding and the energy: France will have the lot. It is too much; he will have to stay.

Previous page

Previous page