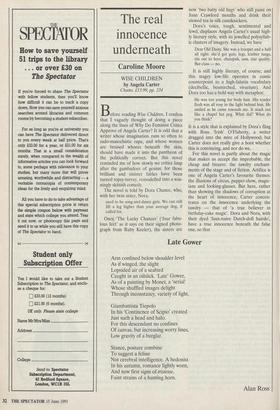

The real innocence underneath

Caroline Moore

WISE CHILDREN by Angela Carter Chatto, £13.99, pp. 234 Before reading Wise Children, I confess that I vaguely thought of doing a piece along the lines of Why Do Feminist Critics Approve of Angela Carter? It is odd that a writer whose imagination runs so often to sado-masochistic rape, and whose women are bruised whores beneath the skin, should have made it into the pantheon of the politically correct. But this novel reminded me of how slowly we critics limp after the gambadoes of genius; for those brilliant and sinister fables have been turned topsy-turvey, remodelled into a win- ningly skittish comedy.

The novel is told by Dora Chance, who, with her twin sister, Nora,

used to be song-and-dance girls. We can still lift a leg higher than your average dog, if called for.

Once 'The Lucky Chances' (lour fabu- lous feet' as it says on their signed photo- graph from Ruby Keeler), the sisters are now 'two batty old hags' who still paint on Joan Crawford mouths and drink their stewed tea in silk camiknickers.

Dora's voice, tough, sentimental and lewd, displaces Angela Carter's usual high- ly literary style, with its jewelled polysyllab- ic clusters of imagery. Instead, we have

Dear Old Daisy. She was a trooper and a half all right: she'd got guts, legs, leather lungs, tits out to here, chutzpah, sass, star quality. But class — no.

It is still highly literary, of course; and this stagey low-life operates in comic counterpoint to a high-falutin vocabulary (decibellic, besmirched, vivarium). And Dora too has a bold way with metaphor: He was too young for body hair. His tender flesh was all rosy in the light behind him. He smiled as he came towards me. It stuck out like a chapel hat peg. What did? What do you think?

It is a style that is explained by Dora's fling with Ross 'Irish' O'Flaherty, a writer dragged into the mire of Hollywood; but Carter does not really give a hoot whether this is convincing, and nor do we.

For this novel is partly about the magic that makes us accept the improbable, the cheap and bizarre: the tawdry enchant- ments of the stage and of fiction. Artifice is one of Angela Carter's favourite themes: the illusions of circus, puppet-show, magic- ians and looking-glasses. But here, rather than showing the shadows of corruption at the heart of innocence, Carter concen- trates on the innocence underlying the tawdry — that of 'a true believer in birthday-cake magic'. Dora and Nora, with their dyed 'faux-naive Dutch-doll hairdo', have a true innocence beneath the false one, so that

the champagne they poured out for us would turn to ginger pop the moment it touched our pretty little, silly little lips.

Nora loses her virginity to a pantomime goose: there are shades here of the sinister feathered rape in Carter's other work; but it was not, Dora maintains

a squalid, furtive, miserable thing, to make love for the first time on a cold night in a back alley with a married man with strong drink on his breath. He was what she wanted, warts and all.

Desire, like the other magic in this novel, is both delusory and transfiguring.

As for the plot, it happily defies synopsis. It includes every theatrical chestnut: bed tricks and substitute marriages, no fewer than five pairs of twins, a girl driven mad by love distributing flowers with snatches of lewd song, returns from the dead and the discovery of long-lost parents, a poisoned birthday cake. The long arm of coincidence is stretched to the point of dislocation; but, like the feckless Nora, the author is swept away by 'a sort of grand carelessness', which is gloriously infectious.

Dora and Nora are the illegitimate child- ren of Sir Melchior Hazard, ex-matinee idol, Shakespearian actor, and, latterly, fruity voice-over on television commercials; his twin brother, Peregrine, is 'adventurer, magician, seducer, explorer, scriptwriter'. Sir Melchior has two other sets of perform- ing twins from his various marriages: Saskia, who is a rapacious TV cook, and Imogen, who is Goldie the Goldfish on a children's programme; Tristram, a game- show host, yodelling 'Lashings of Lolly!', and Gareth, a monk.

The House of Hazard spans the world of showbiz; but it is Dora's and Nora's career that is shown in loving detail: from their first appearance as sparrows in The Babes in the Wood, to a Sheakespearian musical, What You Will (or What! You Will?), to a mega-budget Hollywood floperoo — Sir Melchior's Midsummer Night's Dream, where the kitsch special effects oust the magic of the theatre:

Daisies as big as your head and white as spooks, foxgloves as tall as the tower of Pisa that chimed like bells if shook. . . gigantic false dewdrops, clockwork birds, and wind machines. . .

The film becomes a cult in the sisters' old age, for nostalgia is another insidiously beglamourising force in the novel. Again, its power is cheap and illusory, but real and strong. Dora evokes

the days when bacon in the pan buzzed like a bee in a lavender bush;

the days of Lyons tea shops, and of

a Brixton, before the lights went out over Europe, hub of a wheel of theatres, music

halls, Empires, Royalties, what have you. 'Strange how potent cheap music is!', Sir Melchior remarks; and Wise Children is a bravura celebration of its allure.

The enchantress has done it again.

Previous page

Previous page