ARTS

Exhibitions 1

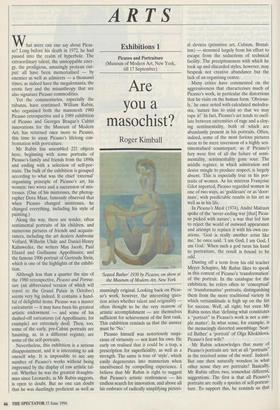

Picasso and Portraiture (Museum of Modern Art, New York, till 17 September)

Are you a masochist?

Roger Kimball

What more can one say about Picas- so? Long before his death in 1972, he had passed into the realm of hyperbole. The extraordinary talent, the unstoppable ener- gy, the prodigious, amazingly protean out- put: all have been memorialised — by enemies as well as admirers — a thousand times, as indeed have the megalomania, the erotic fury and the misanthropy that are also signature Picasso commodities.

Yet the commentaries, especially the tributes, have continued. William Rubin, who organised both the mammoth 1980 Picasso retrospective and a 1989 exhibition of Picasso and Georges Braque's Cubist innovations for the Museum of Modern Art, has returned once more to Picasso, this time to assay Picasso's lifelong con- frontation with portraiture.

Mr Rubin has assembled 221 objects here, beginning with some portraits of Picasso's family and friends from the 1890s and ending with a selection of self-por- traits. The bulk of the exhibition is grouped according to what was the chief 'external' organising principle of Picasso's art, his women: two wives and a succession of mis- tresses. (One of his mistresses, the photog- rapher Dora Maar, famously observed that when Picasso changed mistresses, he changed everything, including his style of painting.) Along the way, there are tender, often sentimental portraits of his children, and numerous pictures of friends and acquain- tances, including the art dealers Ambroise Vollard, Wilhelm Uhde and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the writers Max Jacob, Paul Eluard and Guillaume Appollinaire, and the famous 1906 portrait of Gertrude Stein, which is one of the highlights of the exhibi- tion.

Although less than a quarter the size of the 1980 retrospective, Picasso and Portrai- ture (an abbreviated version of which will travel to the Grand Palais in October) seems very big indeed. It contains a hand- ful of delightful items. Picasso was a master caricaturist — it may have been his greatest artistic endowment — and some of his dashed-off caricatures (of Appollinaire, for example) are extremely droll. Then, too, some of the early, pre-Cubist portraits are haunting, as, in a different register, are some of the self-portraits.

Nevertheless, this exhibition is a serious disappointment, and it is interesting to ask oneself why. It is impossible to see any number of Picasso's works without being impressed by the display of raw artistic tal- ent. Whether he was the greatest draughts- man since Leonardo, as Mr Rubin suggests, is open to doubt. But no one can doubt that he was dazzlingly proficient as well as `Seated Bather' 1930 by Picasso, on show at the Museum of Modern Art, New York stunningly original. Looking back on Picas- so's work, however, the interesting ques- tion arises whether talent and originality often thought to be the very marrow of artistic accomplishment — are themselves sufficient for achievement of the first rank. This exhibition reminds us that the answer must be 'No.'

Picasso himself was notoriously suspi- cious of virtuosity — not least his own. He early on realised that it could be a trap, a prescription for superficiality, as well as a strength. The same is true of 'style', which easily degenerates into mannerism when unenlivened by compelling experience. I believe that Mr Rubin is right to suggest that Picasso's artistic restlessness — his endless search for innovation, and above all his embrace of radically simplifying pictori- al devices (primitive art, Cubism, Brutal- ism) — stemmed largely from his effort to escape from the seductions of technical facility. The precipitousness with which he took up and discarded styles, however, may bespeak not creative abundance but the lack of an organising centre.

Many critics have commented on the aggressiveness that characterises much of Picasso's work, in particular the distortions that he visits on the human form. 'Obvious- ly,' he once noted with calculated melodra- ma, 'nature has to exist so that we may rape it!' In fact, Picasso's art tends to oscil- late between extremities of rage and a cloy- ing sentimentality, both of which are abundantly present in his portraits. Often, indeed, some of the most furious pictures seem to be mere inversions of a highly sen- timentalised counterpart, as if Picasso's fury were first of all the failure of senti- mentality, sentimentality gone sour. The middle register, in which admiration and desire mingle to produce respect, is largely absent. This is especially true in his por- traits of women. As his mistress Frangoise Gilot reported, Picasso regarded women in one of two ways, as 'goddesses' or as 'door- mats', with predictable results in his art as well as in his life.

In Picasso's Mask (1974), Andre Malraux spoke of the 'never-ending war [that] Picas- so picked with nature', a war that led him to reject the world of outward appearance and attempt to replace it with his own cre- ations. 'God is really another artist like me,' he once said. 'I am God, I am God, I am God.' When such a god turns his hand to portraiture, the result is bound to be odd.

Dusting off a term from his old teacher Meyer Schapiro, Mr Rubin likes to speak in this context of Picasso's 'transformation' of the portrait. In the catalogue for the exhibition, he refers often to 'conceptual' or `transformative' portraits, distinguishing them from the more traditional variety in which verisimilitude is high up on the list for success. Well, all right; but even Mr Rubin notes that 'defining what constitutes a "portrait" in Picasso's work is not a sim- ple matter'. In what sense, for example, is the menacingly distorted assemblage 'Seat- ed Bather' a 'portrait' of Olga Khokhlova, Picasso's first wife?

Mr Rubin acknowledges that many of Picasso's portraits are 'not at all "portraits" in the received sense of the word'. Indeed. But one then naturally wonders in what other sense they are portraits? Basically, Mr Rubin offers two, somewhat different, suggestions. The first is that all Picasso's portraits are really a species of self-portrai- ture. To support this, he reminds us that Picasso was fond of quoting Leonardo to the effect that 'the artist always paints him- self It seems to me, though, that Leonar- do is an unreliable source for understanding Picasso. For if he said that `the artist always paints himself,' he also insisted 'that painting is most praiseworthy which is most like the thing represented' a dictum that does not easily cohere with Picasso's more daring experiments.

Mr Rubin's second suggestion is that Picasso, working in an age when photogra- phy began to compete with portraiture, helped to transform the portrait from an `objective' into a 'subjective' enterprise that is, one in which the artist aims not to `memorialise' his subject but rather to express his 'personal response to the sub- ject'. In this sense, he says, Picasso 'rede- fined' the genre of portraiture in much the same way that Renaissance and Baroque artists redefined it in their own eras.

All this makes for a thicket of complica- tions. It is certainly true that, as Mr Rubin puts it, 'the emergence of the transformed portrait subverted almost all of the assump- tions on which the traditional portrait com- mission had been based'. Yet Mr Rubin, like many other critics, wishes to stress the centrality of the 'human image' in Picasso's work. It is an image that is, often as not, distorted beyond recognition. What does that mean? I think Mr Rubin is on safer ground when he suggests that, like the poet Stephan Mallarme, Picasso aimed to describe 'not the thing itself but the effect it produces'. It would seem that for Picasso the effect produced was often distinctly unpleasant.

It is no doubt unfortunate, but one of the first things that came to mind while looking at Picasso and Portraiture was Evelyn Waugh. Readers of Waugh's letters will remember that there was a time in the 1940s when he regularly included the exhortation 'Death to Picasso!' as a kind of valedictory to cheer up — or to irritate his correspondents. Naturally, Waugh spoke mostly in jest. But his campaign against Picasso — and, by extension, all of modernism — had a serious as well as a philistine dimension. Waugh acknowledged Picasso's talent, especially his comic genius. What he objected to, finally, was Picasso's megalomania.

His painting, especially his portraiture, is not so much a 'transformation' of nature, as Mr Rubin would have it, but a revenge exacted upon it for having the effrontery to elude him. Many critics argue that Picasso's fury is an ineluctable reflection of the mod- ern spirit. But there is much in his life and work that suggests that his violent distor- tions are less a response to modernity than the product of a willed dehumanisation. Perhaps this is what Picasso meant when he said that people who liked his paintings `really had to be masochists'.

Roger Kimball is managing editor of the New Criterion.

Previous page

Previous page