Tax Reforms 3

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT At present the possessors of capital get off very lightly. They pay, of course, a heavy stamp duty of 2 per cent. on transfers of capital (which I hope will at least be halved). They pay heavy estate duties on death, but these are largely volun- tary because they can be avoided completely by assigning capital to trusts (provided not less than five years elapse between the signing of the trust and death). They also pay a capital gains tax, which Mr. Lloyd limited to security gains realised within six months, or land sales realised within three years. This was intended to catch the man who trades in securities or land, but he was in fact liable already' to be assessed to income tax on such profits if he was found to be 'trading.' The capital gains of the genuine long-term investor were not affected: they are still tax-free.

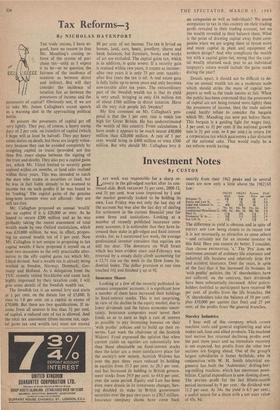

Mr. Callaghan proposed an annual 'wealth' tax on capital if it is £20,000 or over. As he hoped to secure £200 million and as he was probably taking the recent assessment of total wealth made by two Oxford statisticians, which was £20,000 million, he was, in effect, propos- ing an annual wealth tax of 1 per cent. Now Mr. Callaghan is not unique in proposing to tax capital wealth. I have proposed it myself on at least two occasions as the only practicable alter- native to the silly capital gains tax which Mr. Lloyd devised. And a wealth tax is already being worked in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Ger- many and Holland. As a delegation from the TUC recently visited Stockholm and came back highly impressed by their taxation code, I will give some details of the Swedish wealth tax.

The Swedish tax is an annual levy and starts at 1 per cent. on the datum line of £5,600. It rises to 1.8 per cent. on a capital in excess of £70,000. But there are two qualifications. If in- come from all sources is less than 31 per cent. of capital, a reduced rate of tax is allowed. And the total tax assessment (from income tax, capi- tal gains tax and wealth tax) must not exceed 80 per cent. of net income. The tax is levied on houses, land, cars, boats, jewellery, shares and bank balances, but furniture, books and works of art are excluded. The capital gains tax, which is in addition, is quite severe. If a security gain is realised within two years, it counts as income: after two years it is only 75 per cent. taxable : after five years the tax is nil. A real estate gain is fully liable up to seven years and only becomes non-taxable after ten years. The extraordinary part of the Swedish wealth tax is that its yield is very small, bringing in only £16 million out of about £560 million in direct taxation. Have all the very rich people left Sweden?

My first comment on Mr. Callaghan's pro- posal is that the 1 per cent. rate is much too high for Great Britain. He has underestimated- the wealth of this country. From calculations I have made it appears to be much nearer £40,000 million than £20,000 million A rate of 1 per cent. would bring in £400 million or even £500 million. But why should Mr. Callaghan levy it on companies as well as individuals? We assess companies to tax in this country on their trading profit revealed in their trading account, not on the wealth revealed in their balance sheet. What is the point of drawing capital away from com- panies when we are urging them to invest more and more capital in plant and equipment of modern design? And why complicate the wealth tax with a capital gains tax, seeing that the capi- tal wealth returned each year in an individual taxpayer's return would include the gains made during the year?

Details apart, it should not be difficult to de- vise an annual wealth tax on a moderate scale which should strike the mass of capital tax- payers as well as the trade unions as fair. When the public has been convinced that the possessors of capital are not being treated more lightly than the possessors of income, then the trade unions could hardly refuse to consider the bargain. which Mr. Maudling can now put before them. This bargain is a guiding light for wages (say, 3 per cent. to 31 per cent. if the national growth rate is 31 per cent. to 4 per cent.) in return for a corporation tax which guarantees a fair division of the national cake. That would really be a tax reform worth having.

Previous page

Previous page