WALDHEIM AND THE NAZIS

Richard Bassett on the reason

why Dr Waldheim suppressed the details of his war service

Vienna LAST week, most Austrians and certainly all foreign correspondents in Vienna re- cieved an interesting magazine through the post called Portrait. Nothing to do with the glossy of that name in London, its 18 pages were devoted exclusively to pictures of Dr Kurt Waldheim, the former Secretary- General of the United Nations, who is standing in the Austrian presidential elec- tions; the man, so the election rubric runs, 'the whole world trusts'.

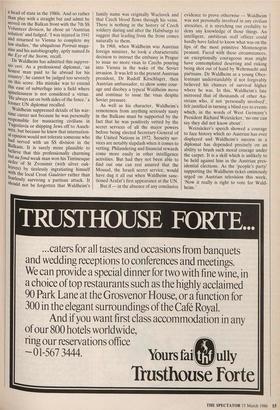

There was Waldheim laughing with Mrs Thatcher, Waldheim listening to Gromy- ko, embracing Reagan, and, most grue- some of all, Waldheim caressing some obedient nephew identified only as 'Stephan'. Somehow, though, there was something missing, something which many Austrians were no doubt delighted to see reproduced on the front page of the Times the same day: Waldheim in a uniform of the Wehrmacht standing rigidly to atten- tion in front of an SS general and his jodhpured adjutant (this last, as could be made out in the clearer later editions, even brandishing a riding-crop). Now if there is any picture of Waldheim which is likely to impress the average Austrian, this is it.

Unlike many Germans, the Austrians have on the whole never felt much guilt about the atrocities of the Third Reich. Only a few months ago, it was possible for their minister of defence, Herr Friedhelin Frischenshlager, to permit the erection of plaque in the military academy com- memorating one General Alexander Lohr. Lohr was executed in Belgrade for war crimes in 1947 and Dr Waldheim served on his staff. It may be recalled that Herr Frischenshlager last year shook hands with another controversial Austrian, former Sturmbahnfiihrer Reder, on his return to the alpine republic. It is tempting at first glance to see this behaviour as confirmation of Asquith 's observation in 1914, 'The Austrians are quite the stupidest people in Europe.' But such actions reveal rather the total failure of the Austrians either to research or properly come to terms with their role in the Thousand-Year Reich'.

In fairness, it should be pointed out that no one after the second world war was interested in saddling an already demoral- ised and supine nation with too much angst about war-guilt. Austria, occupied by the Allies until 1955, had to be restored as a buffer between East and West if it was ner to go the way of Czechoslovakia and Hungary. The less said therefore about all those thousands of strapping hysterical frauleins screaming Tin Reich' on the Heldenplatz when the Fiihrer returned t° his Heimat, the better. Nazi atrocities continue to be thought of as exclusively attributable to the callous Prussians rather than the incompetent Austrians. Dr Waldheim, however unattractive, is not an unintelligent man. He has spent his life as an Austrian diplomat propagating, along with every other Austrian diplonlar; precisely this myopic view of the historY (3' the Third Reich. It is one of the great, achievements of Austrian diplomacy tha,' until Herr Frischenshlager shook hanus with Herr Reder, few people thought r° question this view. As a man moving in international circles, Dr Waldheim, unlike most Austrians wh° have the true provincial's resilience world opinion, was perceptive enough realise that though photographs of hia:n strutting around a Montenegrin airfield jackboots may boost his popularity Austria, it was not quite the right image ha' a head of state in the 1980s. And so rather than play with a straight bat and admit he served on the Balkan front with the 7th SS Volunteer division, he chose an 'Austrian solution' and fudged. 'I was injured in 1941 and returned to Vienna to complete my law studies,' the ubiquitous Portrait maga- zine and his autobiography, aptly named In the Eye of the Storm, recall. Dr Waldheim has admitted this suppres- sto yeti. As a professional diplomat, 'an honest man paid to lie abroad for his country', he cannot be judged too severely on this score. His mistake was to extend this ease of subterfuge into a field where Spinelessness is not considered a virtue. He always sat on both sides of the fence,' a former UN diplomat recalled. Waldheim suppressed details of his war- time career not because he was personally responsible for massacring civilians in Yugoslavia or shipping Jews off to Ausch- witz, but because he knew that internation- al opinion would not tolerate someone who had served with an SS division in the Balkans. It is surely more plausible to believe that this professionally charming but au fond weak man won his Tintinesque order of St Zvonimir (with silver oak- leaves) by tirelessly ingratiating himself With the local Croat Gauleiter rather than fearlessly surviving a partisan attack. It should not be forgotten that Waldheim's family name was originally Waclavek and that Czech blood flows through his veins. There is nothing in the history of Czech soldiery during and after the Habsburgs to suggest that leading from the front comes naturally to them.

In 1968, when Waldheim was Austrian foreign minister, he took a characteristic decision to instruct the embassy in Prague to issue no more visas to Czechs pouring into Vienna in the wake of the Soviet invasion. It was left to the present Austrian president, Dr Rudolf Kirschlager, then Austrian ambassador, to show some cour- age and disobey a typical Waldheim move and continue to issue the visas despite Soviet pressure.

As well as his character, Waldheim's remoteness from anything seriously nasty in the Balkans must be supported by the fact that he was positively vetted by the secret services of all the major powers before being elected Secretary-General of the United Nations in 1972. Security ser- vices are notably slapdash when it comes to vetting. Philandering and financial rewards come more easily in other intelligence activities. But had they not been able to find out one can rest assured that the Mossad, the Israeli secret service, would have dug it all out when Waldheim sanc- tioned Arafat's first appearance at the UN.

But if — in the absence of any conclusive evidence to prove otherwise — Waldheim was not personally involved in any civilian atrocities, it is stretching our credulity to deny any knowledge of those things. An intelligent, ambitious staff officer could hardly have failed to know what was on the lips of the most primitive Montenegrin peasant. Faced with these circumstances, an exceptionally courageous man might have contemplated deserting and risking being shot out of hand by Wehrmacht and partisans. Dr Waldheim as a young Ober- leutnant understandably if not forgivably believed his chances of survival higher where he was. In this, Waldheim's fate mirrored that of thousands of other Au- strians who, if not 'personally involved', felt justified in turning a blind eye to events which, in the words of West Germany's President Richard Weizsacker, `no one can say they did not know about'.

Weizsacker's speech showed a courage to face history which no Austrian has ever displayed and Waldheim's success as a diplomat has depended precisely on an ability to brush such moral courage under the carpet. It is a skill which is unlikely to be held against him in the Austrian pres- idential elections. As the 'people's party' supporting the Waldheim ticket ominously urged on Austrian television this week, 'Now it really is right to vote for Wald- heim.'

Previous page

Previous page