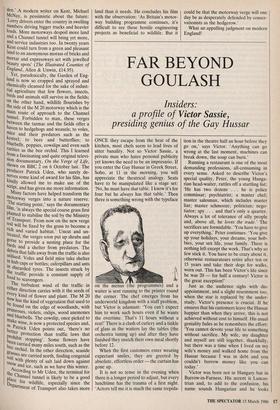

FAR BEYOND GOULASH

Insiders:

a profile of Victor Sassie,

presiding genius of the Gay Hussar

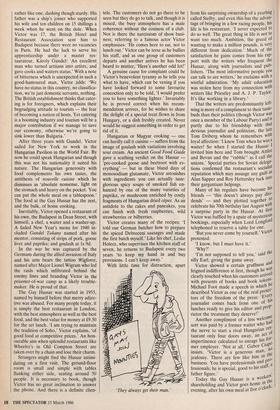

ONCE they escape from the heat of the kitchen, most chefs seem to lead lives of utter banality. Not so Victor Sassie, a private man who hates personal publicity yet knows the need to be an impresario. If you enter the Gay Hussar in Greek Street, Soho, at 11 in the morning, you will appreciate the theatrical analogy. Seats have to be manipulated like a stage set: `No, he must have that table. I know it's for four but he always has that table.' Then there is something wrong with the typeface on the menus (the programmes and a waiter is sent running to the printer round the corner. The chef emerges from his underworld kingdom with a staff problem, but Victor is adamant: 'You can't expect him to work such hours even if he wants the overtime. That's 11 hours without a rest!' There is a clash of cutlery and a tinkle of glass as the waiters lay the tables (the orchestra tuning up) and after they have finished they snatch their own meal shortly before 12.

When the first customers enter wearing expectant smiles, they are greeted by absolute, effortless order — the curtain has gone up. It is not so tense in the evening when there is a longer period to adjust, but every lunchtime has the trauma of a first night. 'Actors tell me it is much the same trepida- tion in the theatre half an hour before they go on,' says Victor. 'Anything can go wrong at the last moment, machines can break down, the soup can burn.'

Running a restaurant is one of the most demanding professions, all-consuming in every sense. Asked to describe Victor's special quality, Peter, the young Hunga- rian head-waiter, rattles off a startling list: `Fle has two dozens . . . he is police commissar; psychiatrist; a master chef; master salesman, which includes master liar; master schmooze; politician; nego- tiator; spy . . . and that's only a quarter. Always a lot of tolerance of silly people and, above all, he loves the trade.' The sacrifices are formidable. 'You have to give up everything,' Peter continues. 'You give up your holidays, your dreams, your hob- bies, your sex life, your family. There is nothing left except the work. That's why so few stick it. You have to be crazy about it, otherwise restaurateurs retire after ten or 15 years and take their dogs for walks, worn out. This has been Victor's life since he was 20 — for half a century! Victor is the great exception!'

Just as the audience sighs with dis- appointment, and a slight resentment too, when the star is replaced by the under- study, Victor's presence is crucial. If he ensures that his customers leave the Hussar happier than when they arrive, this is not achieved without cost to himself. His usual geniality fades as he remembers the effort: 'You cannot devote your life to something without sacrifice. My wife, my daughter and myself are still together, thankfully, but there was a time when I lived on my wife's money and walked home from the Hussar because I was in debt and you couldn't borrow money like you can today.'

Victor was born not in Hungary but in Barrow-in-Furness. His accent is Lancas- trian and, to add to the confusion, his name sounds Hungarian and he looks rather like one, dashing though sturdy. His father was a ship's joiner who supported his wife and ten children on 15 shillings a week when he went on the dole. When Victor was 17, the British Hotel and Restaurant Association sent him to Budapest because there were no vacancies in Paris. He had the luck to serve his apprenticeship under a master res- taurateur, Karoly Gundel: 'An excellent man who turned artisans into artists, and gave cooks and waiters status.' With a note of bitterness which is unexpected in such a good-humoured man, Victor adds: 'We have no status in this country, no classifica- tion, we're just domestic servants, nothing. The British establishment thinks that cater- ing is for foreigners, which explains their begrudging attitude to tourists — the fear of becoming a nation of hosts. Yet catering is a booming industry and tourism will be a major contribution if we manage to save our economy, otherwise we're going to sink lower than Bulgaria.'

After three years with Gundel, Victor sailed for New York to work in the Hungarian Pavilion in the World Fair. By now he could speak Hungarian and though this was not his nationality it suited his nature. The Hungarian generosity with food complements his own tastes, the antithesis of nouvelle cuisine which he dismisses as 'absolute nonsense, light on the stomach and heavy on the pocket. You can put the whole meal on a tablespoon.' The food at the Gay Hussar has the zest, and the bulk, of home cooking.

Inevitably, Victor opened a restaurant of his own, the Budapest in Dean Street, with himself, a chef, a waiter and a washer-up. A faded New Year's menu for 1940 in- cluded Gundel Tokany named after his mentor, consisting of strips of pork, goose liver and paprika; and goulash at is 9d.

In the war he was captured by the Germans during the allied invasion of Italy and his arm bears the tattoo Wigforce, named after Major Lionel Wigram who led the raids which infiltrated behind the enemy lines and branding Victor in the prisoner-of-war camp as a likely trouble- maker. He is proud of that.

The Gay Hussar was started in 1953, named by himself before that merry adjec- tive was abused. For many people today, it is simply the best restaurant in London, with the best atmosphere as well as the best food, and the best value for money at £9.50 for the set lunch. 'I am trying to maintain the tradition of Soho,' Victor explains, 'of good food at competitive prices.' An hon- ourable aim when splendid restaurants like Wheeler's in Old Compton Street are taken over by a chain and lose their charm.

Strangers might find the Hussar intimi- dating on a first visit. The ground-floor room is small and simple with tables flanking either side, seating around 50 people. It is necessary to book, though Victor has no great inclination to answer the phone. And there is a definite clien- tele. The customers do not go there to be seen but they do go to talk, and though it is mixed, the busy atmosphere has a male coherence without the cosiness of a club. Nor is there the narcissism of show busi- ness; referring to a famous actor Victor emphasises: 'He comes here to eat, not to lunch out.' Victor can be terse as he bullies his staff, and as one group of customers departs and another arrives he has been heard to mutter, 'Here's another odd lot!'

A genuine cause for complaint could be Victor's benevolent tyranny as he tells you what to have, which can be vexing if you have looked forward to some favourite concoction only to be told, 'I would prefer you to have something lighter.' Invariably he is proved correct when his recom- mendation arrives, for he wishes to share the delight of a special treat flown in from Hungary, or a dish freshly created. Never would he suggest something in order to get rid of it.

Hungarian or Magyar cooking — one can hardly call it cuisine — suffers from the image of goulash with variations involving sour cream. An ancient Good Food Guide gave a scathing verdict on the Hussar — 'pre-cooked goose and beetroot with ev- erything' — but in these bland days of monosodium glutamate, Victor astonishes with ingredients you can actually taste: glorious spicy soups of smoked fish en- hanced by one of the many varieties of paprika, or mushroom enriched by costly fragments of Hungarian dried cepes. As an antidote to the cakes and pancakes, you can finish with fresh raspberries, wild strawberries or bilberries.

Victor creates many of the recipes: 'I told our German butcher how to prepare the spiced Debreceni sausages and made the first batch myself.' Like his chef, Leslie Holecz, who supervises the kitchen staff of seven, he returns to Budapest every two years 'to keep my hand in and buy provisions. I can't keep away.'

With little time for distraction, apart 'They always get their man.' from his surprising ownership of a yearling called Stelby, and even this has the advan- tage of bringing in a few racing people, his life is his restaurant. 'I never expected to do so well. The great thing in life is not to want too much. Ambition, the greed of wanting to make a million pounds, is very different from dedication.' Much of the satisfaction he gains comes from his rap- port with the writers who frequent the Hussar, along with journalists and pub- lishers. 'The most informative people you can talk to are writers,' he exclaims with a wistful admiration. 'My adult education was stolen here from my connection with writers like Priestley and A. J. P. Taylor, It's like working in a library.' That the writers are predominantly left- wing is more of a compliment to their taste buds than their politics (though Victor was once a member of the Labour Party) and is partly due to his friendship with that devious journalist and politician, the late Tom Driberg whom he remembers with loyal affection: 'I knew Tom when he was a waiter! So when I started the Hussar I invited him here and Tom brought Attlee and Bevan and the "rabble" as I call the unions.' Special parties for Soviet delega- tions confirmed the restaurant's socialist reputation which may assuage any guilt as Alan Sapper and Roy Hattersley tuck int° their gargantuan helpings. Many of his regulars have become his friends — 'this doesn't always pay divi- dends' — and they plotted together re celebrate his 70th birthday last August with a surprise party in the Hussar. At firSt Victor was baffled by a spate of mysterious bookings, especially when Lord Longford telephoned to reserve a table for one. 'But you never come by yourself,' Victor protested.

'I know, but I must have it.'

'Why?' 'I'm not supposed to tell you,' said the silly Earl, giving the game away. Victor showed a certain gruffness and feigned indifference at first, though he Was, clearly touched when his customers arrive ° with presents of books and book tokens. Michael Foot made a speech in which he described Victor as one of the real proree- tors of the freedom of the press: Ever"' journalist comes back from one of lunches ready to give his editor and pr°1P- rietor the treatment they deserve!' Another compliment of a less welconlei sort was paid by a former waiter who ho the nerve to start a rival Hungarian res: taurant only four doors away, an act 01 impertinence calculated to enrage his for- mer employer. 'Not at all,' Gabor Cs3P°0 insists. 'Victor is a generous man, 11,e jealousy. There are few like him in V' business. You have professionals and Pr°: fessionals; he is special, good to his staff, " father figure.' Today the Gay Hussar is awor kers shareholding and Victor goes home in W. evening, after his own meal at five o' 1 clo°‘ unless there is a special party. 'I'll carry on until one of the staff convinces me that he wants to run it and can run it. I'm hopeful they'll elect their own chairman and con- tinue rather than put it on the market.' Should Labour return to power, it would be a nice gesture if they repaid his services with a knighthood. In France he would be venerated. In England, at least he is a much-loved man.

Previous page

Previous page