Crafts

For love or money

Tanya Harrod on the strains felt by the second generation of Arts and Crafts workers Most of us work to live, rather than live to work; but the men and women of the Arts and Crafts movement made joy in labour central to their existence. Again and again, reading the lives and letters of late 19th- and early 20th-century makers, we come across vivid accounts of delight. For instance, the printer J.H. Mason, on joining T.J. Cobden Sanderson's Doves Press in 1900 after an earlier career at a commer- cial printing house, remembered a real atmosphere of exaltation, as though we were concerned with some high service to something outside and above us, and were truly working for work's sake.

At a different end of the social scale, Sir George Trevelyan remembered starting as an apprentice in 1929 in the furniture workshop of Peter Waals:

That springtime for me has never faded. There was such endless joy in losing oneself in the making of things.

. An almost erotic sense of pleasure, this time at the discovery of a particular skill, is echoed in Eric Gill's account of first seeing Edward Johnston's calligraphy in 1899: ... the first time I saw him writing and saw the writing that came as he wrote, I had that thrill and tremble of the heart which other- wise I can only remember having had when I first touched her body or saw her hair down for the first time, or when I first heard the plain chant of the church.

We find it again in J.H. Mason's account of creating a private-press book:

It is almost like falling in love, with all the delighted service and bringing of presents, and decorations, illustration, and fine gar- ments of handmade paper and binding.

Two principal types of joy are recorded. There was that of a skilled 'trade' crafts- man like Mason entering a new world where work was elevated above mere effi- ciency and cost-effectiveness and taken closer to the practice of art. Then there was the release felt by an upper- or middle- class individual — for instance, George Trevelyan or another furniture-maker, A. Romney Green — on turning from intel- lectual to physical work. As Romney Green wrote in his autobiography of the drudgery of planing wood :

There is no lovelier exercise in the world . It takes every muscle in your body from the soles of your feet to the tips of your fin- gers.

But the children of this curious breed of idealistic handworkers had a more difficult row to hoe. I can immediately think of the sons of two pre-eminent potters whose lives have in many ways been overshadowed by the powerful personalities and reputations of their fathers. For them, the harsher eco- nomics of the post-second world war world and their need to develop and build on the newly forged 'tradition' of their fathers weighed heavily. The paradoxical careers of the second generation of these Arts and Crafts families is beautifully expounded by Anne Carruthers in her recent biography of the furniture-maker Edward Barnsley (Edward Barnsley and his Workshop: Arts and Crafts in the Twentieth Century, White Cockade Publishing, Oxford).

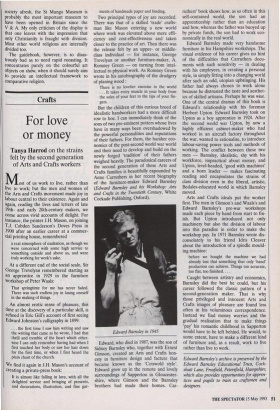

Edward Barnsley in 1945 Edward, who died in 1987, was the son of Sidney Barnsley who, together with Ernest Gimson, created an Arts and Crafts hon- esty in furniture design and facture that became known as the 'Cotswold style'. Edward grew up in the remote and lovely surroundings of Sapperton in Gloucester- shire, where Gimson and the Barnsley brothers had made their homes. Car- ruthers' book shows how, as so often in this self-contained world, the son had an apprenticeship rather than an education and how, whereas the father was buoyed up by private funds, the son had to work eco- nomically in the real world.

Edward Barnsley made very handsome furniture in his Hampshire workshops. The visual evidence of his career gives no hint of the difficulties that Carruthers docu- ments with such sensitivity — in dealing with his employees, in creating a personal style, in simply fitting into a changing world after such an odd, utopian upbringing. His father had always chosen to work alone because he distrusted the taste and aesthet- ics of skilled artisans. Perhaps he was wise. One of the central dramas of this book is Edward's relationship with his foreman Herbert Upton. Edward Barnsley took on Upton as a boy apprentice in 1924. After the second world war Upton, by now a highly efficient cabinet-maker who had worked in an aircraft factory throughout the war, wanted to rationalise, to introduce labour-saving power tools and methods of working. The conflict between these two men — Barnsley, idealistic, shy with his workforce, impractical about money, and Upton, level-headed, 'good with machines' and a born leader — makes fascinating reading and encapsulates the strains of class division even in the liberal, artistic, Bedales-educated world in which Barnsley moved.

Arts and Crafts ideals put the worker first. The men in Gimson's and Waals's and Edward Barnsley's pre-war workshops made each piece by hand from start to fin- ish. But Upton introduced not only machinery but also the division of labour into this paradise in order to make the workshop pay. In 1971 Barnsley wrote dis- consolately to his friend Idris Cleaver about the introduction of a spindle mould- ing machine:

before we bought the machine we had already lost that something that only 'hand' production can achieve. Things too accurate, too flat, too finished. . . .

Caught between artistry and economics, Barnsley did the best he could, but his career followed the classic pattern of a second-generation maker. That is why those privileged and innocent Arts and Crafts images of pleasure are found less often in his voluminous correspondence. Instead we find money worries and the gradual realisation that to make things `pay' his romantic childhood in Sapperton would have to be left behind. He would; to some extent, have to make a different kind of furniture and, as a result, work to live rather than live to work.

Edward Barnsley's archive is preserved by the Edward Barnsley Educational Trust, Cock- shutt Lane, Froxfield, Petersfteld, Hampshire, which also provides opportunities for appren- tices and pupils to train as craftsmen and designers.

Previous page

Previous page