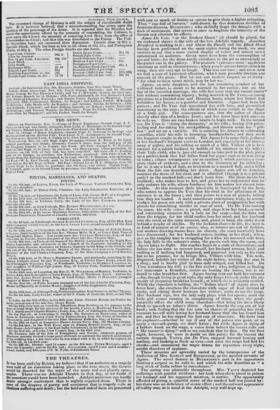

THE THEATRES.

Jr has been said (by BURKE, we believe) that if an audience at a tragedy were told of an execution taking place in the next street, the theatre would be deserted for the scene of the more real and ghastly caw- trophe. There was no Adelphi Theatre in that day, or we doubt if the assertion would have been hazarded. Adelphi audiences can hardly desire stronger excitement than is nightly supplied them. There is pone of the drapery of poetry and sentiment that in tragedy veils or idealizes suffering and death ; but the bold and naked facts are presented with just so much of fiction as serves to give them a higher colouring. They " sup full of horrors," cold-drawn by that dexterous distiller of domestic distress, Breics.rosE; who skilfully drugs the draught with a dash of merriment, that serves at once to heighten the intensity of the flavour and alleviate its effects.

Agnes De Vere, " or the Broken heart" (it should be plural, for we reckoned three) is the title of the last Adelphi tragedy. Jonathan Bradford is nothing to it : and Oscar the Bandit and the Bleach Hand having been performed on the same nights during the week, we may venture to say that it more varied display of crime and misery never entertained an audience. Great must have been the consumption of gin and beer—for the dram-bottle circulates in the pit as extensively as the porter-can in the fallery. The proverb "extremes meet " applies to emotions as well as circumstances ; when people are too horror-struck to weep, they are very apt to laugh. This was our case : and even now we feel a sort of hysterical affection, which may possibly tincture our account of the piece. But let not our readers suspect us of levity " for what to them seems mirth, may be but %v."' Agnes, till only daughter, and the hist remaining comfort of her widowed father, is about to be married to her cousin ; but on the day of the intended marriage, she tells her lover that she cannot marry.. him without committing bigamy; being married to De Vere,—a young physician in a braided coat and Hessian boots, whom her father had forbidden his house, as a gambler and libertine. Agnes had been his patient; and be Vere bad inoculated her with love, and prescribed matrimony as the cure ; the effects of which were visible in the shape of a little girl. The consequences are, that the father of Agnes shortly after dies of a broken heart ; and her lover lives with one—so he tells us. Here are two broken hearts to begin with. In the second act, De Vere is "doing the domestic," at his villa ; buying left pulse- feeling and fee-taking for stockjobbing, and thrown aside his " pill- box " and set up a curriele. He is amusing his leisure in cultivating camellias, while his wife is hemming handkerchiefs ; and they seem the happiest couple in the world. But Agnes feels some little jealousy at her husband's frequent visits to London, and especially at his staying away o' nights, and his talking so much of a Mrs. Villiers (it is very natural for a rakish husband to babble of his mistress to his wife): their little child, who is just old enough to take part in the plot, picks up a pocket-book that had fallen from her papa's coat us lie was going to town ; (these scrapegraces are so careless!) which contains a com- plete chain of evidence, and it clue to the discovery of his infidelity; for in it are a lock of hair, an invitation to a masked ball, and a billet from the fair one describing her dress. Agnes sets off to London, assumes the dress of her rival, and is admitted (though it is a private party) to the masked ball—we don't learn how. She there meets her husband ; who makes love to her, and gives her to understand that he only endures his wife, whose fondness for him makes her almost into- lerable. At this moment their tae-d-it"te, is interrupted by the host, who enters to apprize De Vere that his rival in the affections of his mistress is at the house ; and then points to a case of pistols, telling him they are loaded. A most considerate entertainer, truly, to accom- modate they guest not only with a private place of assignationebut with pistols for committing murder in case of need. On De Vere leaving the room, his wife seizes a pistol, and claps it to her head,—a novel and interesting situation for a lady on the stage,—but she does not draw the trigger, for her child rushes into her mind, and her husband into the room at the same moment, and, pistol in band, she sinks down behind a trophy of shields. By the luckiest chance in life, the host is as fond of armour as of an amour, else, as screens are out of fashion, and modern drawing-rooms have no closets, she must inevitably have been discovered ; for her husband enters, leading in her rival ; when, just as the naughty man is struggling for a kiss, his incensed wife fires, the lady falls in the seducer's arms, the guests rush into the room, and Agnes takes to flight. She reaches home in a state of distraction ; and before she has time to recover herself, her husband returns, brisk and smiling as if nothing had happened, and punctual not only to his time but to his promise, for he brings Mrs. Villiers with him. The wife, disgusted, beholds her victim of the night before, wearing her arm in a sling; and is hardly glad to have only winged, not killed her. De Vere introduces his wife to the fair visiter ; who, indignant at finding her inamorato a Benedick, insists on leaving the house, but is in- duced to take breakfast first. Agnes having sent out both her servants —for, though living in great style, she only keeps two—is under the ne- cessity of preparing breakfast herself; at which she is evidently nettled. While the chocolate is boiling, the" Italian blood" of Agnes rises to fever heat ; she sweetens the chocolate with sugar of lead instead of candy, and sitting down between her victims., waits to see the issue. Her husband sips, but the lady only plays with her spoon ; untirthe little girl comes running in complaining of thirst, when she good- naturedly offers the child some chocolate—that being the most likely drink to quench an infant's thirst. Agnes knocks the cup out of her hand ; and, finding that she has now no chance of poisoning her rival, contents herself with letting her husband know that she has found him out, and that he has sipped his last cup of chocolate. He darts intd his cupboard—whether to see if any of the poison was gone, or to apply a stomach-pump, we don't know ; but while Agnes is dying of a broken heart on the stage, a voice from behind the scenes calls out " My master is dying!" and so we conclude that he dies. On the first night, however, we were in doubt on this point ; for the instant the curtain dropped, YATES, the De Vere, stepped forward bowing and smiling, and looking as fresh as ever—not even the rouge had fled his cheeks—and announced the tragic drama for repetition every night, amidst thunders of applause. These miseries are agreeably varied by the interspersion of the drolleries of Mrs. KEELEY and BUCKSTONE, as the married servants of Agnes. The novel feature in BecxsroisE's part is his appearance blowing a serpent as he calls it, and which his wife describes as " a long stick of India rubber in convulsions."

The acting was admirable throughout. Mrs. YATES depicted her sufferings with painful vividness : her look when she is about to poison her husband and his supposed mistress, is terrific. The opportunity afforded of giving a splendid scene of the masked ball was passed by: but there was no deficiency of scenic effect ; nod the outward appearance of reality was, as is usual at the Adelphi, very well kept up. This piece is said to be by the author of Victorine : but in that beau- tiful drama the painful impressions were effaced by a delightful picture of bemble happiness. The audience woke with the heroine from a frightful dream, to "the sober certainty of waking bliss ;" and went away wiser and better. Tales of sheer misery like Agnes De Vere do but deaden the sensibilities they excite. The feelings are shocked, but the moral sense is untouched, by these concatenations of revolting incidents, intended solely to " milk the maudlin eyes" of morbid or obtuse natures. Let such go to Bedlam or Newgate, and leave the theatre to those who seek more rational amusetneet.

Previous page

Previous page