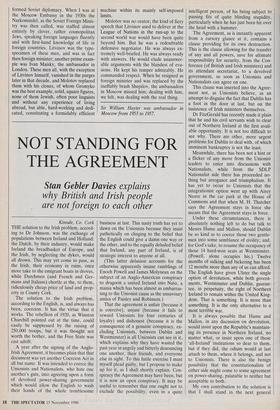

THE ABOMINABLE NO-MAN

William Hayter remembers Molotov,

survivor from the most ruthless dictatorship in history

SUPERFICIALLY, Molotov was some- what ridiculous. The Foreign Office nick- name for him was Auntie Moll (paired with Stalin as Uncle Joe); this seemed to suit his round, pallid face, adorned with pince-nez. His unconquerable stutter didn't help. He seemed like a small-time bureaucrat. When I was driving with Bulganin and Khrushchev on their visit to London in 1956 they were astonished at the number of bowler hats they saw in the street, and wondered if any of their comrades had ever worn one; they were amused to think that comrade Molotov almost certainly had. Molotov even seemed to find himself a little ludicrous; when, during the foreign ministers' conference in Berlin in 1954, he told a lie so outrageous that everyone laughed, he joined in the laughter.

Yet with all this he remained a formid- able figure. By the time of Stalin's death he was the only remaining Old Bolshevik of any stature; Stalin had had all the rest put to death. He lived through the whole terrible Russian history of this century; he had participated in the Revolution of October 1917, he had been the first editor of Pravda, he had been a member of the first Party Committee set up after the revolution, he had lived through and shared in all the horrors and destructions of war communism, the Stalin purges, the Nazi-Soviet pact and the second world war, all the time as a loyal subaltern of one of the most ruthless dictators the world has ever known. At the end of his life Stalin was beginning to become suspicious of him, exiling his Jewish wife and accusing him, absurdly, of Zionism; Stalin's death may well have saved him from exile and perhaps from execution. In spite of this he almost alone seemed to have genuinely mourned Stalin's death; foreign ambassa- dors found him in tears when they called to condole. He survived for a time under Stalin's successors but turned against them when they turned against Stalin. In his old master's time this would have been the end of him, but in fact he was allowed the equivalent of an honourable retirement.

In political contacts with Western repre- sentatives he easily earned his other nick- name of the Abominable No-man. In this he was only his master's voice while Stalin was alive, and even after his death. In social contexts he was surprisingly affable and even tactful. He would not, for inst- ance, when entertaining foreign ambassa- dors, propose toasts that they could not drink, as Khrushchev was very liable to do. There was a notable example of this contrast at a dinner which the Politburo gave for visiting delegations to the Tushino air show in 1956; on this occasion Khrush- chev got very drunk (Molotov was never seen in this condition) and began propos- ing toasts to China, which the United States ambassador was then obliged to refuse, and to East Germany, which none of the Western governments had then recognised. Khrushchev went on to make a number of remarks insulting to practically every country in the world. Molotov, drumming his fingers irritatedly on the table, said to Malenkov across the Amer- ican ambassadress. 'All this is very un- necessary,' and after rising for one of Khrushchev's drunken toasts remained standing and broke the party up.

It would hardly be possible to say that Molotov was a man of any originality; he was too much the social subordinate to show himself in that light. Nevertheless his impact on world history in this century was considerable. For one thing, he trans- formed Soviet diplomacy. When I was at the Moscow Embassy in the 1930s the Narkomindel, as the Soviet Foreign Minis- try was then called, was staffed almost entirely by clever, rather cosmopolitan Jews, speaking foreign languages fluently and with first-hand knowledge of life in foreign countries. Litvinov was the type- specimen of these men, and was in fact then foreign minister; another prime exam- ple was Ivan Maisky, the ambassador in London. These men all, with the exception of Litvinov himself, vanished in the purges later in that decade, and Molotov replaced them with his clones, of whom Gromyko was the best example, solid, square figures, none of them Jewish, often poor linguists and without any experience of living abroad, but able, hard-working and dedi- cated, constituting a formidably efficient machine within its mainly self-imposed limits.

Molotov was no orator; the kind of fiery speech that Litvinov used to deliver at the League of Nations in the run-up to the second world war would have been quite beyond him. But he was a redoubtable defensive negotiator. He was always ex- tremely well-briefed. He was always ready with answers. He would elude unanswer- able arguments with the blandest of eva- sions. He kept his temper admirably. He commanded respect. When he resigned as foreign minister and was replaced by the ineffably brash Shepilov, the ambassadors in Moscow missed him; dealing with him, we felt, was dealing with the real thing.

Sir William Hayter was ambassador in Moscow from 1953 to 1957.

Previous page

Previous page