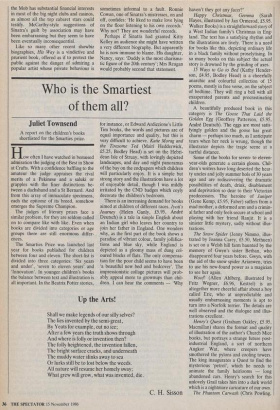

The importance of being Frank

Patrick Skene Catling

HIS WAY: THE UNAUTHORISED BIOGRAPHY by Kitty Kelley

Bantam, f12.95

Hell hath no fury like a biographer scorned. Kitty scratches hard but this immense, trivial biography of America's legendary, pre-eminent saloon singer has almost certainly enhanced his reputation, at least where it matters to him, in his own country. His way is the American way. Money, power and fame are the ultimate desiderata, and if the means to those ends are a bit bent here and there — well, as long as you don't get caught and you make it to the top, scandal is glamorous and scores extra machismo points.

In a prefatory note, the author com- plains that Sinatra ignored several letters requesting interviews. So did his publicity agent. And so, up to a point, did Sinatra's lawyer. After four years of this importun- ate pestering, Sinatra sought an injunction to stop her from publishing his biography. Who can blame him for trying? He must have had a good idea of what it would be like. This 'celebrated investigative journal- ist', as her British publisher calls her, had already written Jackie Oh! and Elizabeth Taylor: The Last Star. Behind Kitty Kel- ley's pert, kewpie-doll grin lies a middle- aged brain with a highly developed talent to offend.

Sinatra imprudently also sued Miss Kel- ley for $2 million in punitive damages. One of his grievances, she writes, was that she was misrepresenting herself 'as his official biographer to get "inside knowledge of the Private aspects or events of [his] life".'

A group of writers' organisations came to her defence. Among them were the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Sigma Delta Chi (Society of Profes- sional Journalists), the Newspaper Guild (America's equivalent of the NUJ), PEN, the American Society of Journalists and Authors, the National Writers' Union, the Council of Writers' Organisations, and Washington Independent Writers. In pub- lic statements, they cited the First Amendement of the United States Con- stitution, which guarantees that 'Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.' That admirable statute protects malicious muck- raking gossips as well as Nobel laureates.

After a year of litigation, Sinatra real- ised that he could not win. He asked the court to dismiss his suit. The writers hailed its dismissal as 'a victory for all writers and the public. It reaffirms the right of the public to be informed about the lives of influential public persons whether or not they approve of the writer and his or her approach.'

With the help of the Freedom of In- formation Act, Miss Kelley obtained pre- viously unpublished transcripts of FBI wiretaps and testimony presented at closed hearings of crime commissions. An obviously industrious freedom fighter, she interviewed more than 800 persons who had been close to Sinatra, more or less, some of them too close for comfort, including members and ex-members of his family. She was able to question some men known to have connections with the Mafia.

So what's the dirt dished up in these 575 grey pages?

Francis Albert Sinatra was born 70 years ago in Hoboken, New Jersey, the tough maritime city where the film On The Waterfront was made. His mother, Dolly, was an abortionist and an active democrat on the ward level, where political influence could be peddled for favours. She had wanted a girl and at first she dressed her skinny little son in pink dresses. Later he graduated to Little Lord Fauntleroy suits. She always gave him more money than the neighbours' children had. According to Miss Kelley, he used some of it to buy friendship, a habit which has persisted all his life.

Miss Kelley records an early peccadillo of Sinatra's right on page one. He was arrested for adultery in 1938, when he was a singing waiter:

The next day a Hoboken newspaper car- ried a story headlined: 'Songbird Held in Morals Charge,' but no one in Hoboken paid much attention. They were accustomed to seeing the Sinatra name in print for getting into trouble with the law. Frank's uncle Dominick, a boxer known as Champ Sieger, had been charged with malicious mischief; his uncle Gus had been arrested several times for running numbers; his other uncle, Babe, had been charged with participating in a murder and had been sent to prison. His father, Marty, was once charged with receiv- ing stolen goods, and his mother, Dolly, was regularly in and out of courthouses for performing illegal abortions. And Frank himself had been arrested just a month before on a seduction charge.

Miss Kelley records in relentless detail the many ups and downs of Sinatra's singing and acting career and of his person- al relationships with all sorts of people, from 'Lucky' Luciano and other notorious gangsters to President Kennedy and Presi- dent Reagan. Her prose is generally utilita- rian but now and then she tries for some fancy effects, as when she describes Sinatra during his Tommy Dorsey period as 'the frail singer with the face of a debauched faun' (rude but quite well put) and when she writes of Dolly's social ambition that she 'wanted to wear Hoboken like a ribbon in her hair' (awful). There are plenty of gaudy quotes and occasional mal- appropriately funny ones, such as a confes- sion by Ava Gardner, Sinatra's most beautiful, most tempestuous wife: 'Deep down, I'm pretty superficial.' In the words of one confused acquaintance, Judith Campbell, 'Frank's Mr Hyde was a charmer, but his Dr Jekyll was frightening, truly frightening.' Sinatra, himself, proudly claimed that the Inaugural gala which he organised for President Reagan 'jelled like clockwork.'

Miss Kelley competently rehearses the familiar story of Sinatra's spectacular suc- cess at the Paramount Theatre in New York in 1942, when adolescent girls were paid to simulate ecstasy and the vapours whenever the singer began to sing. She tells also of his difficulties when he suffered an attack of 'hysterical aphonia', paralysis of the vocal cords, at the Copacabana in 1950, and of his triumphant, Oscar- winning comeback three years later, in From Here to Eternity.

She boringly records various inconclu- sive official interrogations, for example by Senator Kefauver's Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce, in 1950, which failed to establish that Sinatra carried a large sum of Mafia money to Luciano in exile in Cuba. Further investigations by grand juries, the Internal Revenue Service, a congressional commit- tee and the New Jersey State Crime Commission — bad luck for Miss Kelley were similarly unsuccessful in proving any- thing beyond the fact that he has habitually consorted with some very shady charac- ters, most notably in Nevada, New Jersey and New York. But that's show business: the Mob has substantial financial interests in most of the big night clubs and casinos, as almost all the top cabaret stars could testify. McCarthy-style suggestions of Sinatra's guilt by association may have been embarrassing but they seem to have been eventually inconsequential.

Like so many other recent showbiz biographies, His Way is a vindictive and prurient book, offered as if to protect the public against the danger of admiring a popular artist whose private behaviour is sometimes informal to a fault. Ronnie Cowan, one of Sinatra's mistresses, on and off, confides: 'He liked to make love lying on the floor listening to his own records.' Why not? They are wonderful records.

Perhaps if Sinatra had granted Kitty Kelley an audience she might have written a very different biography. But apparently he is now immune to blame. His daughter, Nancy, says: 'Daddy is the most charisma- tic figure of the 20th century'; Mrs Reagan would probably second that statement.

Previous page

Previous page