THE ECONOMY & THE CITY

Money and Aid

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT

s the Minister of Overseas Development said in her excellent guide-book to aid: 'Since several major donor countries face balance of payments problems, theft is a constant threat to lie flow of aid.* She added: 'For these reasons we attach great importance to improvements in lite international monetary system.'* This may be a passing dig at her colleague, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, but I am sure that Mr. Callaghan must be convinced by this time-after attending the dreary IMF meeting at Washington -that there is not much point in reforming the international monetary system unless it makes things easier for the poorer half of the world. For the rich countries to open up a new reserve account-on the French or American model- to be drawn upon solely by themselves would get us all nowhere. It would be an insult to the poor.

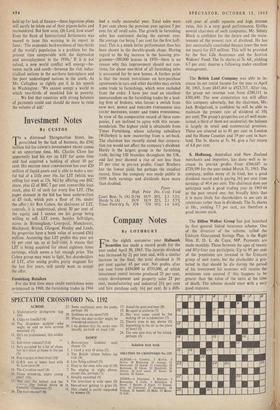

We do not have to be Shavians to feel that the poor are a great social and political nuisance -on the international front. While the rich de- veloped nations can be relied upon to get richer and richer year by year, the poor, less-developed nations let the world down by becoming rela- tively poorer. Here is the tell-tale table from Mrs. Castle's text: Income (Gross Domestic Product)

Average annual growth rate %

'50-55 '55-60 '60-63 Developed countries .. 4.7 3.4 4.4

Leks developed countries ..

4.6 4.5 4.0

Population

Developed countries 1.2 1.3 1.3

Less developed countries .. income IG DP per capita)

2.1 2.3 2.6 Developed countries .. 3.4 2.1 3.1 Less developed countries .. 2.5 2.1 1.5 It is all too obvious that the less-developed nations are breeding too fast. The growth of their agricultural output has long since fallen below the growth of their populations. (In Latin America and the Far East farm output per head is still below the levels of the 1930s.) Much is being done to encourage birth control, but few would deny that in those countries which give family allowances the loss of these allowances if a fourth child were born would be a better pre- ventive than the pill.

Mrs. Castle gives other reasons why the eco- nomic development of the poorer countries has been -slowing down. First, there has been a grow- ing shortage of professional and technical per- sonnel. This is being tackled vigorously by the World Bank, which devoted last year more re, sources of staff and funds to technical assistance than ever before ($4.5 million rising to $6.5 million in 1966). Second, t,here has been a grow- ing shortage of foreign exchange. This has been due not only to the fall in primary commodity prices, but to the increasing cost of financial services. -Mr. Woods, the director of the World 'auk, has been greatly concerned about this growing burden and gives this alarming table in his latest report (1964-65):

Public Debt Service (Amortisation and Interest) Thirty-seven Developing Countries n 1956 1962 1964

America

a Lati

. $455m. $1,280m. $1.442m,

Al% • • • . $117m. $440m. $583m.

E • • • . • $37m. $104m. $131m.

urooe $71m. $174m. $341m.

$680m. 51,998m. $2.497m. The Public debt of these thirty-seven countries

reached a total of no less than $25,000 million in 1964, the service of it costing nearly 10 per cent. It is small wonder that the servicing of debt takes up from 40 pet' cent to 50 per cent of the foreign exchange receipts of some poor nations. As Mrs. Castle says, this is threatening to limit their development. Fortunately, Britain has fol- lowed the example of the World Bank sub- sidiary IDA in giving some interest-free loans.

Believe it or not, the flow of official assistance to the developing countries has actually been de- clining in the last few years-to under $6,000 million-but happily there was an increase in total aid last year-to $8,700 million-because of a substantial rise in the flow of private capi- tal. (Note that British official aid has been steadily increasing and reached £189.6 million in 1964- 65.) As a percentage of their national incomes, the total aid disbursed by the donor countries was lower than it was in 1962, being 0.96 per cent against 1.04 per cent. (The UK percentage was 1.09 and the highest was France with 1.94.) This is not nearly good enough. In the excellent 1965 review of Development Assistance Efforts and Policies, published by the OECD, there is a warn- ing that the private capital flow to the less- developed countries is likely to fall- away as the result of the measures taken by the American and British governments to limit their investment overseas. Mr. Callaghan may therefore have to re- consider his overseas taxation if the poor, developing countries are seen to suffer. He may have to take a leaf out of the German tax book and grant faster depreciation rates and allow- ances to companies investing in the under- developed as opposed to the developed countries.

In the end the Development Assistance Com- mittee of the OECD will have to consider more seriously the Stamp or Wilson plans. Maxwell Stamp proposed that the IMF should increase international liquidity by a fixed amount each year by investing in the developing countries- preferably through the International Develop- ment Association. The developing countries would get certificates from the IMF to enable them to buy goods or services from the-developed in- dustrialised countries which would treat these cer- tificates as additions to their gold reserves. To avoid inflationary results, the industrialised coun- tries-the 'Group of Ten' perhaps-might be allowed to control at the outset the total amount of credit to be created, but the highly corn- (nendable feature of the Stamp scheme was that the developing countries would be the owners of the new assets to be created. The Wilson plan was similar to the Stamp plan. It was propounded by our Prime Minister when he went to Wash- ington in 1963 .and proposed that the IMF should be given central banking powers to assist coun- tries in payments difficulties or with unemployed resources. It was his idea that the IMF should create credits for a new international investment fund which would link the needs of the under- developed with the unemployed resources of the developed nations. Neither plan would be popular with the present gold fanatics of the French school, but when the industrialised nations are eventually facing unemployment-because their exports to the poorer,half of the world are being * OVPRSFAS DEVELOPMINT. (Cmnd. 2736).

held Up for lack of finance-these ingenious plans will surely be taken out of their pigeon-holes and reconsidered. But how soon, Oh Lord, how soon? Even the Bank of International Settlements was moved to issue this warning in its report in June: 'The economic backwardness of two-thirds of the world's population is a problem for the present time comparable with the depression and unemployment in the 1930s.' If it is not solved, a new .world conflict will emerge-be- tween north and south-between the rich indus- trialised nations in the northern hemisphere and the poor undeveloped nations in the south. As Mr. Callaghan so rightly put it in his speech in Washington: 'We cannot accept a world in which two-thirds of mankind live in poverty. . . . We feel that countries with strong balances of payments could and should do more to raise the volume of aid.'

Previous page

Previous page