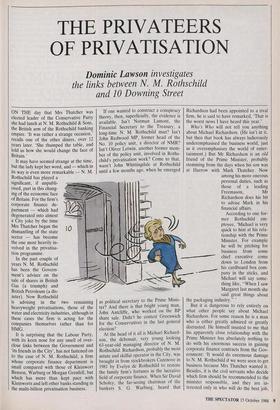

THE PRIVATEERS OF PRIVATISATION

Dominic Lawson investigates

the links between N. M. Rothschild and 10 Downing Street

ON THE day that Mrs Thatcher was elected leader of the Conservative Party she had lunch at N. M. Rothschild & Sons, the British arm of the Rothschild banking empire. 'It was rather a strange occasion,' recalls one of the other diners, over 12 years later. 'She thumped the table, and told us how she would change the face of Britain.'

It is surprising that the Labour Party, with its keen nose for any smell of over- close links between the Government and its friends in the City', has not fastened on to the case of N. M. Rothschild, a firm whose corporate finance department is small compared with those of Kleinwort Benson, Warburg or Morgan Grenfell, but which has more than kept pace with Kleinworts and left other banks standing in the multi-billion privatisation business.

If one wanted to construct a conspiracy theory, then, superficially, the evidence is available. Isn't Norman Lamont, the Financial Secretary to the Treasury, a long-time N. M. Rothschild man? Isn't John Redwood MP, former head of the No. 10 policy unit, a director of NMR? Isn't Oliver Letwin, another former mem- ber of the policy unit, involved in Roths- child's privatisation work? Come to that, wasn't John Whittingdale at Rothschild until a few months ago, when he emerged as political secretary to the Prime Minis- ter? And there is that bright young man, John Antcliffe, who worked on the BP share sale, Didn't he contest Greenwich for the Conservatives in the last general election?

At the head of it all is Michael Richard- son, the debonair, very young looking 63-year-old managing director of N. M. Rothschild. Richardson, probably the most astute and skilful operator in the City, was brought in from stockbrokers Cazenove in 1981 by Evelyn de Rothschild to restore the family firm's fortunes in the lucrative field of corporate finance. When Sir David Scholey, the far-seeing chairman of the bankers S. G. Warburg, heard that Richardson had been appointed to a rival firm, he is said to have remarked, 'That is the worst news I have heard this year.'

Who's Who will not tell you anything about Michael Richardson. (He isn't in it, but then that book has always ludicrously underemphasised the business world, just as it overemphasises the world of enter- tainment.) But Mr Richardson is an old friend of the Prime Minister, probably stemming from the days when his son was at Harrow with Mark Thatcher. Now among his more onerous personal duties, such as those of a leading

Freemason, Mr Richardson does his bit to advise Mark in his financial affairs.

According to one for- mer Rothschild em- ployee, 'Michael is very quick to hint at his rela- tionship with the Prime Minister. For example he will be pitching for business from some chief executive come down to London from his cardboard box com- pany in the sticks, and Michael will say some- thing like, "When I saw Margaret last month she said great things about the packaging industry." '

But it is dangerous to rely entirely on what other people say about Michael Richardson. For some reason he is a man who is either greatly admired or greatly distrusted. He himself insisted to me that his apparently close relationship with the Prime Minister has absolutely nothing to do with his enormous success in gaining corporate finance contracts from the Gov- ernment: 'It would do enormous damage to N, M. Rothschild if we were seen to get business because Mrs Thatcher wanted it. Besides, it is the civil servants who decide which firm should be recommended to the minister responsible, and they are in- terested only in who will do the best job,

and who will cause their minister least embarrassment in front of the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Commons.'

Indeed, there is some evidence that Michael Richardson's closeness to the Prime Minister — which he does not keep a secret — may even have lost him some business. Insiders believe that one reason why Rothschilds failed to get the job of advising British Steel on its privatisation may have been that Sir Robert Scholey, the company's chairman, felt that Richard- son was a bit too close to the PM. After all, privatisations tend to feature disputes be- tween the advisers of the company which want the shares to be sold at a price so cheap as to make modest demands of management's future performance — and the Government, which wants the highest price the market will bear.

But what about all those card-carrying Tories in Mr Richardson's corporate fi- nance department? Are their credentials useful in getting government business? Richardson insists — and he is a formid- ably persuasive man, as the sub- underwriters of the BP share issue know to their considerable financial embarrassment — 'I have never let any of our ex-No. 10 people work on business in which we are advising the Government. It would be most improper.'

Where the likes of John Redwood, and, latterly, Oliver Letwin have been set to work, is in the advising of foreign govern- ments on their privatisations. There is no doubt that Richardson's strategy of picking the intellectual architects of Britain's trail- blazing privatisations mightily impresses other administrations looking for help in the dismantling of their own public sectors. Against ferocious competition N. M. Rothschild has won the job of advising the Spanish government on the $8 billion sale of Repsol, the state oil monopolist. Other NMR privatisation contracts include advis- ing Malaysia on selling its railways, Singa- pore its water, Chile its electricity industry, Jamaica its National Commercial Bank, and Turkey its state pulp and paper com- pany. Some of these may sound trivial, but far from being merely the icing on the cake, these contracts are potentially much more lucrative than any of the work done for the British Government. British ministers and civil servants, through long experience, have become past masters at extracting extremely tight terms from their advisors. By the time of the BP share sale underwri- ters stood to gain only £18,000 per £100 million of stock underwritten, so even if the issue had not been a disaster the profits would have been tiny. But foreign govern- ments are typically less adept at striking such hard bargains. Just as well, since it is likely that Rothschild's own multi-million pound losses as a sub-underwriter of the BP issue were probably large enough to wipe out all the fees it had made in advising the Government on the privatisations of the past decade.

It is difficult to know exactly how much N. M. Rothschild has made or lost out of privatisation, since it is a resolutely private company (most unusual in the City these days), technically owned by Rothschild Continuation in the Swiss canton of Zug, actually controlled by Evelyn de Roth- schild, chairman of N. M. Rothschild. NMR's 1988 consolidated profit and loss account shows only that the company made enough to pay the dividend of £3.75 million (out of a balance sheet of £3.7 billion) to Evelyn and a few other much smaller shareholders. This figure is completely meaningless since, as the accounts note, it is stated, 'after making a transfer to inner reserves'.

According to one former Rothschild man, 'It won't worry Evelyn if Rothschilds has not made a fortune out of the UK privatisation work. First, he is not short of a penny or two. And, although he is not a Tory, he loves the idea that NMR is once again wheeler-dealing in the corridors of power, sitting at the high table.' Perhaps it even reminds him of his antecedent, the original Nathan Mayer Rothschild, who founded NMR in 1804, and who made his mark in this country by cultivating the British Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Herries, and financing the Peninsular cam- paigns of Wellington against Napoleon.

In some ways Michael Richardson him- self is a throwback to the 19th-century way of doing business in the City. His career was built at Cazenove, the most prestigious and old-style of the stockbroking firms, whose strength comes not so much from what it knows as who it knows. It is very much in this style that Richardson has packed Rothschild with young men who might be very useful indeed to have known in 20 years' time.

But one ex-Rothschild employee pointed out to me, 'There's nothing new in Rothschild having Tory MPs on its shelf. Usually they were in asset management, such as Norman Lamont. The point was, when we had lost a bundle on some big client's portfolio it was handy to bring along a Tory MP when we tried to explain to the client why everything would turn out well in the end. Don't ask me why, but it seemed to help.' Indeed John Redwood, although he had not yet become an MP, was at Rothschild Asset Management be- fore he took over at the No. 10 policy unit.

New or not, the Rothschild habit of employing actual or putative Tory MPs marks it out from its main merchant banking rivals. A Warburg director told me rather archly, 'We don't like to employ people with ambitions outside the firm. Working in our corporate finance depart- ment should take more than 100 per cent of anyone's time.'

At Kleinwort Benson, which up to 1984 was virtually the unanimous choice of ministers to act as their adviser on priva-

tisation (British Aerospace, Cable & Wire- less, Enterprise Oil, British Telecom) there is some sort of political culture. But it seems to be to the left of the Conservative Party. One of Kleinwort's directors is Tom Chandos, SDP economic spokesman in the House of Lords. And until recently Klein- wort Grieveson, the securities arm of the firm, enjoyed the advice and company of Bernard Donoghue, a former adviser to Harold Wilson and Jim Callaghan.

When Kleinworts wants to hire bright people from outside the City it turns not to the No. 10 policy unit, but to the civil service. One such is Callum McCarthy, now a director of the firm, who was Cecil Parkinson's principal private secretary when he was Secretary of State at the Department of Trade and Industry.

It would not be altogether surprising if Michael Richardson secretly thinks that Cecil Parkinson chose Kleinworts to advise him on the privatisation of the electricity supply industry in part because of his old link with Callum McCarthy. It is certainly the first time that KB has acted for the Government in a full-scale privatisation since 1984. But Mr McCarthy angrily describes such suggestions of ministerial favouritism as 'complete and utter rubbish. We were selected on merit, just as I am sure that Michael Richardson's team at Rothschilds were selected on merit for all their government work.'

Traditionally, merchant banks are sup- posed to be piratical opportunists, able to work on either side of any deal, or for any government. This is certainly the view of the Kleinwort director who, when I asked if his firm would happily advise a future Labour government on the nationalisation of a private sector company, replied, 'Of course. We are technicians. If people tell us what they want to do, we'll tell them the most efficient way to do it.'

Michael Richardson clearly knew this `correct' answer when I put the same question to him, but he was unwilling to give it. Instead, looking rather anguished, he replied that 'nationalisation is against all my personal beliefs; I wouldn't be very keen to assist a future government on such a policy.'

However, as Evelyn de Rothschild would doubtless be the first to remind Mr Richardson, the Rothschild tradition is one of business before politics. In Derek Wil- son's recently published Rothschild: a Story of Wealth and Power there is a wonderful illustration of this principle, in an account by Ernest Feydeau of a scene in Paris within days of the declaration of a republic in 1848. The writer saw Baron James de Rothschild walking towards the Tuileries as the bullets whizzed overhead. Rothschild had been a staunch financial supporter and adviser to the ancien regime, but his first act on the outbreak of revolu- tion was to offer his services to the new regime, even though he detested it. Feydeau recalled that he stopped the

Baron, brother of Nathan Mayer Roths- child, saying he feared for his safety. But the Baron said that he was merely carrying out his 'duty . . . to go to de Ministry of Finance to zee vedder dey may not neet my hexperience and my gounzel'.

The chances are that if the political status quo in this country were to change

dramatically the firm of N. M Rothschild, and Michael Richardson, would perform an analogous pilgrimage, even if it meant jettisoning some of their more recently acquired ideological baggage. Whether they would be met with open armed approval by those new political powers is a matter of greater conjecture.

Previous page

Previous page