ARTS

Cinema

Eisenstein 1898-1948: His Life and Work (Hayward, till 11 December)

Sergei goes to Hollywood

Adrian Dannatt

lies on a maggoty carcase, svelte shoppers fingering furs: sitting in the cine- ma watching such swiftly cross-cut images — the latest advertisement for Lynx, the anti-fur organisation — it is obvious that Eisenstein is still very much with us. Indeed, the dead meat of this advertise- ment is practically a direct homage to the horrific sight of the felled bull in Eisen- stein's Strike of 1924.

The famous Russian film-maker, whose 90th anniversary is celebrated in this ex- hibition, is clearly more than an academic relic of the silent era. Eisenstein occupies contemporary cinema, all cinema, like a benign phantom, his ideas, his images, his obsessional modernity being, if anything, rather too bold for our present mild, narrowly narratory modes. The exhibition rescues Eisenstein from the domain of the `silent classics', that barren world of Carl Davis scores and polite applause at the NFT, and reminds us of the potential of film to re-order reality, not just humbly record it.

Fascinated by the latest innovations, Eisenstein reacted to the advent of sound with a short note: 'The first experiments in sound must aim at a sharp discord with the visual images.' It took some 40 years, and Jean-Luc Godard, for this idea to be put fully into practice, and rather than being the 'first experiments', such films are still considered the final frontiers of the ex- treme avant-garde. Likewise, the full potential of Eisenstein's famous idea of `montage' has only really been explored by the likes of Nic Roeg, to the bafflement and outrage of the public.

Those film-makers too shy, or too shrewd, to explore the possibilites of his theory are not averse to quoting his images as easy evidence of cineaste integrity, visual shorthand for 'art-cinema'. Brian de Palma's The Untouchables climaxed with a brilliant pastiche of Eisenstein's most famous sequence, the rolling pram of the Odessa Steps, from Battleship Potemkin.

Characteristically, this exhibition reveals that Eisenstein only had the idea for the famous Steps massacre after seeing how cherry-stones bounced down as he spat them out. For as well as reminding us of his contemporaneity, this show gives us a surprising and refreshing image of Eisen- stein, less as the deeply serious revolution- ary film-maker, a figure of awesome gravi- tas, rather as a saucy maverick, a jester of the international avant-garde, an eclectic cosmopolitan. Instead of the one- dimensional hero of every film society, we are treated to a complex, dazzling poly- math, a cartoonist; costume designer, opera producer and clown.

The first display, a reconstruction of his Moscow study, provides all the clues, starting with the blazing yellow walls and snazzy dressing-gown. There is a portrait of Joyce on the wall, the bookshelves are clotted with evidence of his diverse read- ing, his deep love of books in themselves, Lautreamont next to Edward Lear, Stein- berg's cartoons next to Daumier's. On the wall is a faux-naif portrait of him, looking like an exact hybrid of Cocteau and Orson Welles, an exceedingly apt conjunction.

Like Cocteau, Eisenstein was as much a draughtsman as a film-maker, and much of this exhibition is devoted to his graphics, which is perhaps unfortunate as they lack the skill of Cocteau and the drama of his film work. Like Cocteau his interests were dizzyingly wide, from Freud and panto- mime to Marx and dance, and equally similarly he liked to see himself as a flaneur, a dandy-observer of world culture, high and low.

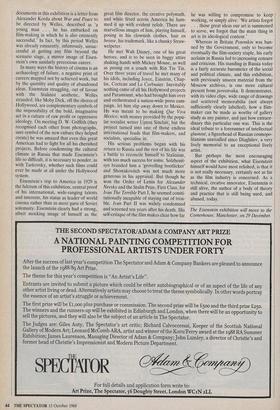

Like Welles he was an early starter, coming to fame at 27 with Potemkin as Welles had found glory at 25 with Kane. Amongst the many fascinating, unexpected A complex, dazzling polymath, jester of the avant-garde: Eisenstein on the set of 'October' documents in this exhibition is a letter from Alexander Korda about War and Peace to be directed by Welles, described as 'a young man . . . he has embarked on film-making in which he is also eminently successful.' In fact, by this period Welles was already eminently, infamously, unsuc- cessful at getting any film beyond the scenario stage, a mirror image of Eisen- stein's own similarly precocious career.

In many ways the history of cinema is an archaeology of failure, a negative print of careers mapped not by achieved work, but by the quantity and quality of abandoned ideas. Eisenstein struggling, out of favour with the Stalinist aesthetic, Welles stranded, like Moby Dick, off the shores of Hollywood, are complementary symbols of the impossibility of the bold, imaginative act in a culture of raw profit or oppressive ideology. On meeting D. W. Griffith (they recognised each other from photographs, sure symbol of the new culture they helped create) he was amazed that even this great American had to fight for all his cherished projects. Before condemning the cultural climate in Russia that made Eisenstein's life so difficult, it is necessary to ponder, as with Tarkovsky, whether such films could ever be made at all under the Hollywood system.

Eisenstein's trip to America in 1929 is the fulcrum of this exhibition, central proof of his international, wide-ranging talents and interests, his status as leader of world cinema rather than as mere guru of Soviet solemnity. Eisenstein clearly had a strong, albeit mocking image of himself as the

great film director, the creative polymath, and while feted across America he ham- med it up with evident relish. There are marvellous images of him, playing himself, posing in his clownish clothes, hair en brosse, his trademark, like a chunky Struw- welpeter.

He met Walt Disney, one of his great heroes, and is to be seen in baggy attire shaking hands with Mickey Mouse, as well as posing on a couch with Rin Tin Tin. Over three years of travel he met many of his idols, including Joyce, Einstein, Chap- lin, Cocteau and Le Corbusier. Inevitably nothing came of all his Hollywood projects and Paramount, who had brought him over and orchestrated a nation-wide press cam- paign, let him slip away down to Mexico. He was meant to be making Que Viva Mexico, with money provided by the popu- lar socialist writer Upton Sinclair, but the project turned into one of those endless international feuds that film-makers, and socialists, specialise in.

His serious problems began with his return to Russia and the rest of his life was a battle to reconcile himself to Stalinism, with too much success for some. Solzhenit- syn branded him a 'grovelling bootlicker' and Shostakovitch was not much more generous in his appraisal. But though he won the Order of Lenin for Alexander Nevsky and the Stalin Prize, First Class, for Ivan The Terrible Part I, he seemed consti- tutionally incapable of staying out of trou- ble. Ivan Part II was widely condemned and screened ten years after his death. His self-critique of the film makes clear how far

he was willing to compromise to keep working, or simply alive: 'We artists forgot . . those great ideas our art is summoned to serve, we forgot that the main thing in art is its ideological content.'

Whereas in Britain Potemkin was ban- ned by the Government, only to become eventually the film-society staple, his early acclaim in Russia led to increasing censure and criticism. His standing in Russia today is a fairly accurate barometer of the social and political climate, and this exhibition, with previously unseen material from the Moscow archives, is one more cultural present from perestroika. It demonstrates, with its video clips, wide range of drawings and scattered memorabilia (not always sufficiently clearly labelled), how a film- maker can be made as worthy of gallery study as any painter, and just how extraor- dinary this particular one was. This is the ideal tribute to a forerunner of intellectual glasnost, a figurehead of Russian cosmopo- litanism unrivalled since Diaghilev, a very lively memorial to an exceptional lively artist.

But perhaps the most encouraging aspect of the exhibition, what Eisenstein himself would have most relished, is that it is not really necessary, certainly not as far as the film industry is concerned. As a technical, creative innovator, Eisenstein is still alive, the author of a body of theory and practice that is still being used, and abused, today.

The Eisenstein exhibition will move to the Cornerhouse, Manchester, on 29 December.

Previous page

Previous page