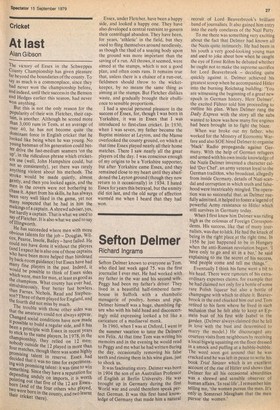

Sefton Delmer

Richard Ingrams Sefton Delmer known to everyone as Tom. who died last week aged 75, was the first journalist I ever met. He had worked with my father in the war and his second wife, Peggy had been my father's driver. They lived in a beautiful half-timbered farmhouse in Suffolk with a shambolic menagerie of poultry, horses and pigs. Delmer himself was a huge. shambling figure who with his bald head and disconcertingly mild expressing looked a bit like a caricature of a mediaeval monk.

In 1960, when I was at Oxford. I went irr the summer vacation to tutor the Dehners' son Felix. At that time Tom was writing his memoirs and in the evening he would read to Peggy and me what he had written during the day, occasionally removing his false teeth and rinsing them in his wine glass, just to shock us.

It was fascinating story. Delmer was born in 1904 the son of an Australian Professor of English at Berlin University, He was brought up in Germany during the first World war and could therefore speak perfect German. It was this first hand knowledge of Germany that made him a natural recruit of Lord Beaverbrook's brilliant band of journalists, It also gained him entry into the early conclaves of the Nazi Party.

To me there was something very exciting about the fact that Delmer had known all the Nazis quite intimately. He had been in his youth a very good-looking young man and used to joke about how when he caught the eye of Ernst Rohm he debated whether he ought not to make the supreme sacrifice for Lord Beaverbrook — deciding quite quickly against it. Delmer achieved his greatest scoop when he accompanied Hitler into the burning Reichstag building: 'You are witnessing the beginning of a great new epoch in German history, Herr Delmer', the excited Fehrer told him proceeding to outline his plan. When Delmer rang the Daily Express with the story all the subs wanted to know 'was how many fire engines had been brought in to fight the blaze.

When war broke out my father, who worked for the Ministry of Economic Warfare and also SOE hired Delmer to organise 'black' Radio propaganda against Germany. With the help of German refugees and armed with his own inside knowledge of the Nazis Delmer invented a character called 'Der Chef', an army veteran loyal to the German tradition. who broadcast. allegedly from inside Germany, details of Nazi scan. dal and corruption in which truth and falsehood were inextricably mingled. The operation was so successful that, as Delmer ruefully admitted, it helped to foster a legend of powerful Army resistance to Hitler which still survives in Germany today.

When I first knew him Delmer was riding high as the colossus of Foreign Correspondents. His success, like that of many journalists, was due to hick. He had the knack of being in the right place at the right time. In 1956 he just happened to be in Hungary when the anti-Russian revolution began. 'I have only to go and sit in a bar,' he said explaining to me the secret of his success, 'and people come and tell me things,' Eventually I think his fame went a bit to his head. There were remours of his extraordinary expenses claims, for example that he had claimed not only for a bottle of some rare Polish liqueur but also a bottle of champagne with which to dilute it. Beaverbrook in the end clucked him out and Tom retired to his farm where he lived in such seclusion that he felt able to keep an Epstein bust of his first wife Isabel in the garden. (Delmer always claimed that he fell in love with the bust and determined to marry the model.) He discouraged any courtesy visits from neighbours by receiving a local bigwig squatting on the floor dressed in a smock and puffing at a hubble-bubble. The word soon got around that he was cracked and he was left in peace to write his book Trial Sinister which is an excellent account of the rise of Hitler and shows that Delmer for all his occasional absurdities was a shrewd and sensible observer of human affairs, 'In real life', I remember him telling me, 'the women pursue the men. It's only in Somerset Maugharn that the men pursue the women.'

Previous page

Previous page