THE ECONOMY & THE CITY

Living with Mr. Callaghan

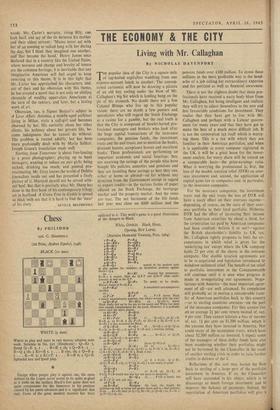

By NICHOLAS DAVENPORT Min! popular idea of the City is a square mile of top-hatted capitalists waddling from one expense-account lunch to another. The conven- tional cartoonist will now be drawing a picture of an old boy reeling under the blow of Mr. Callaghan's big fist which is landing bang on the pit of his stomach. No doubt there are a few Colonel Blimps who live up to this popular vision; there are no doubt a few punters and speculators who still regard the Stock Exchange as a casino for a gamble, but the real truth is that the City is composed of bowler-hatted pro- fessional managers and brokers who look after the huge capital transactions of the insurance companies, the pension funds, the investment trusts and the unit trusts, not to mention the banks, discount houses, acceptance houses and merchant banks. These professionals are performing an important economic and social function; they are receiving the savings of the people who have bought life policies, annuities and pensions and they are investing these savings as best they can, either at home or abroad—so far without any direction from the Government except in regard to export credits—in the various forms of paper offered on the Stock Exchange, the mortgage market and the property market. And the sums are vast. The net increment of the life funds last year was close on £600 million and the pension funds over £300 million. To invest these millions in the most profitable way is the head- ache of a job calling for extraordinary expertise and for -political as well as financial awareness.

There is not the slightest doubt that these pro- fessionals have received a nasty body blow from Mr. Callaghan, but being intelligent and realistic they will try to adjust themselves to the new and less favourable conditions for investment. They realise that they have got to live with Mr. Callaghan and perhaps with a Labour govern- ment for many years and that they have got to make the best of a much more difficult job. It is not the corporation tax itself which is worry- ing them. This is a tax with which they are familiar in their American portfolios, and when it is applicable to every company registered in the UK it will be a great boon for the invest- ment analyst, for every share will be valued on a comparable basis—the price-earnings ratio. What is worrying the professional is, first, the loss of the double taxation relief (DTR) on over- seas investment and, second, the application of capital gains tax to companies and, in particular, to the insurance companies.

For the insurance companies, the investment trusts and the unit trusts the loss of DTR will have a nasty effect on their overseas income-- depending, of course, on the ratio of their over- seas portfolio to their total portfolio. Hitherto, DTR had the effect of increasing their income from American securities by about a third, for the corporation tax paid by American companies had been credited—believe it or not!—against the British shareholder's liability to UK tax. Mr. Callaghan rightly proposes to limit the cir- cumstances in which relief is given for the 'underlying tax' except where the UK company holds 25 per cent of the shares in the overseas company. Our double taxation agreements arc to be re-negotiated and legislation introduced to withdraw unilateral relief. The benefit of tax relief to portfolio investment in the Commonwealth will continue until it is seen what progress is made in re-negotiating our agreements. Nego- tiations with America—the most important agree- ment of all—are well advanced. Its completion will probably set in motion a considerable trans- fer of American portfolios back to this country —or to sterling countries overseas—on the part of the insurance companies. For they cannot live on an average 21 per cent return instead of, say, 4 per cent. They cannot tolerate a loss of income of, say, l per cent on $1,500 million, which is the amount they have invested in America. Nor could many of the investment trusts, which have about $2,500 million so invested. I expect some of the managers of these dollar funds have also been wondering whether their portfolios might not be borrowed by the Chancellor in the event of another sterling crisis in order to raise further credits in defence of the £.

Reflections of this sort may hasten the flow back to sterling of a large part of the portfolio investment in America. If so, the Chancellor will have succeeded in his object, which is to discourage so much foreign investment and to improve the balance of payments. Indeed. the repatriation of American portfolios will give a good boost to the sterling exchange, for the Chancellor now requires the seller of foreign securities to exchange into sterling at the official rate the equivalent—in investment currency— of 25 per cent of the proceeds of the sale. Hitherto, all foreign security sales (including sales of direct investments) went into the invest- ment dollar pool, either for reinvestment in other foreign securities or for sale at the current pre- mium. The broad effect, as the Chancellor -said, will be to diminish the private portfolio hold- ings of foreign securities because of the diver- sion to the official reserves of the equivalent of 25 per cent of the sales.

As regaeds the capital gains tax, this will be a shock to the managers of the life assurance funds worse than the loss of DTR. Hitherto, they have been able to conduct their switching ppera- tions in the gilt-edged market and take their profits on equity shares free of tax. Only in the annuity departments did they pay tax on capital profits. Now the life assurance business is highly competitive. The companies which can declare the highest bonuses on their with-profits policies have the strongest pull in the insurance broker market and these bonuses are earned by the clever exploitation and manipulation of their in- vestment funds. If the capital gains tax puts an end to profitable switching in the gilt-edged market, I fear that many bonuses will not be earned. The switching operations run into big figures. The life funds hold about £2,000 million of British government stocks out of a total of £14,500 million in private hands. The flexibility of the gilt-edged market will never be the same if these switching operations are cut short.

The capital gains tax is a form of double taxation. Companies will be taxed, on their capi- tal gains as though they were income and their shareholders will also be taxed on the gains which they make on disposal of their shares. Happily, holders of with-profits policies will not pay tax on their bonuses when their life or en- dowment policies mature, but will -the bonus gains be worth saving for in future? In the case of unit trusts and investment trusts, the net capi- tal gains on which tax has been paid by the trust will be deducted pro rata from the taxable gain of the shareholder. But I can see tax ad- vantages in being a unit-holder in a unit trust and disadvantages in being the shareholder of an investment trust. Perhaps the most popular way out will be to channel public savings in future into life assurance through the medium of a unit trust portfolio. All the repercussions of the tax revolution have not yet been seen.

Previous page

Previous page