A social democrat for the new Europe

Jane McKerron

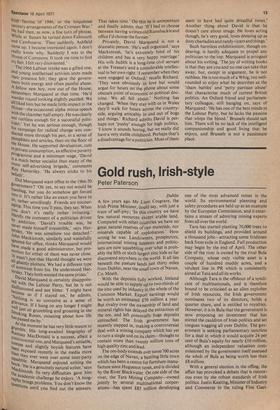

David Marquand, forty-two, Labour MP for Ashfield since 1966, is the latest victim of the Westminster brain drain. His bespectacled, loping presence will shortly be absent from the corridors of the Commons, transferred instead to the more modern environment of Brussels. As Chief Advisor in the Secretariat-General, he will be in charge of liaison between the European Commission, its Parliament in Luxembourg and Strasburg, and the Social Partners Bureau.

Marquand is the most recent of Hugh Gaitskell's legacy of intellectuals to leave British politics, and he won't be the last. With Roy Jenkins already across the water, Tony Crosland tragically gone, David Owen enshrined in the Foreign Office, Shirley Williams and Roy Hattersley sweating over their dispatch boxes, he was one of the few Gaitskellite loyalists left on the back benches. One who remains, albeit part-time, is John Mackintosh. 'I'll miss David enormously', he says, 'We never bore each other, and who will I eat with in this place when he's gone? But he's right to go to Europe. He's bored with our machine.'

Marquand. admits to a considerable capacity for ennui in general, and certainly with the British political system. He described it in a recent article as 'profoundly, perhaps fatally sick'. Weary of being one of 'the poor bloody infantry of the democratic process' at Westminster, Europe has positive attractions. 'What really irritates me about British politicians is their insularity. European politicians like Willy Brandt have been tested through adversity and it shows. They are far less parochial. When I'm with them I find myself becoming curiously more leftwing. The left in Europe is much more board-minded and exciting to be with.' He's also convinced that British political preoccupations are out of date: 'Devolution and direct votes to the European Parliament are all about preserving the nation state. We can't achieve anything within the limits of the nation state. It'scrumbling'.

His discontent began stirring in the early 'seventies but despite the chance of several academic posts, he hung on. There was a chance Roy Jenkins might get the party leadership and Marquand is a loyal lieutenant. 'When Roy wasn't elected I was really ready to go'. But he does not want anyone to think of him as a Jenkins lapdog, paddling across the Channel in his master's wake. 'My decision to leave Westminster was entirely personal. Call it a crisis of midi:tie age if you like. I just sat down and thought, what's the best way to spend the rest of my active life? There are absolutely no lessons there for anyone else'. He adds, with candour, that of course he 'may have made a mistake. 'I often wake up in the night in a cold sweat. It may be a wild and rash experiment, but for me, half activist and half academic, it is pure challenge'.

This combination of political and academic temperament is recalled by David's younger brother, Richard. As children they were both politically aware; their father was Hilary Marquand, MP for Cardiff East and Minister of Health in the Attlee government. 'David was terrifically excited in 1945 when he won. He was only eleven, but he jumped up and down in my father's campaign car tooting the horn, I thought he was mad'. Richard also recalls David's endless capacity for academic debate and passion for history. At Oxford he chose to read History rather than PPE and to occupy him

self with the Labour Club rather than the more competitive, glamorous atmosphere of the Oxford Union. •

After Oxford Marquand continued to flirt with academic and political activities. He taught at the University of California, was greatly impressed by Crosland's The Future of Socialism, and attracted to Hugh Gaitskell's view of social democracy. fie was adopted as Labour candidate for Barr in 1962. 'It was a hopeless seat', Richard says, 'But he nursed it very seriously'. After the '64 election he taught polities at Sussex. 'I'd sort of gone off politics', he recalls, though just previously, with true Gaitskellite fervour, he had written a letter to the Sunday Times describing nationalisation 'as about an effective a bogy for this generation as the Irish famine of 1846, or the iniquitous sanitary arrangements of the Crimean War. He had then, as now, a fine turn of phrase. While at Sussex he turned down Falmouth and Cambourne. 'Then suddenly Ashfield came up. I became interested again. I don t really know why. Suddenly I was in the House of Commons. It took me time to find InY feet. I felt very disoriented.'

The 1966 Labour intake was a gifted one,

and young intellectual activists soon made their presence felt; they gave the government both energy and often painful abuse. A fellow new boy, now out of the House, remembers Marquand at that time. 'He'd Wander round looking slightly puzzled. We all liked him but he made little impact in the House---the occasional alpha minus speech With the chamber half-empty. He wasclearly !Int ruthless enough for a successful politician.' Yet he was serious enough, though his campaign for radical change was conducted more through his pen, in a series of Pamphlets and articles, than on the floor of !ne House. He supported devaluation, cuts In private consumption, an effective poverty Programme and a minimum wage. 'David Is a much better socialist than many of the 2Ore self-advertising brigade,' comments rc-0Y Hattersley. 'He always sticks to his beliefs'.

Did Marquand want office in the 1966-70

government ? 'Oh yes, to say not would be 11. umbug, but you do somehow get forced 11?10 it. It's rather like an exam you have to rather unwillingly_ Friends are encouraging, This time you'll pass, they say. When L°1.1 don't it's really rather irritating. KtlardlY the comment of a politician driven 'I' ambition. 'David's trouble was, he :lever made himself irresistible,' says HatJ'ersleY, 'He was somehowtoo detached.' -131Th Mackintosh, similarly and wastefully !griored for office, thinks Marquand would nlaVe Made a good administrator, but pro,1111 ntion for either of them was never close. wasn't just that Harold thought we were 4.1.t ghastly plotters. We had a different type °I ambition from his. He understood HatersleY, They both wanted the same prizes.' te David Marquand is certainly disappoin,_,51, with the Labour Party, but he is not `Lisiilusioned and not bitter. might have .veme°rne so if I stayed on,' he admits. °illing is so corrosive as a sense of gwrievance. If I hung on any longer I might sell Just sit grumbling and groaning in the htn°king Room, moaning about how life `Las Passed me by.' At the moment he has very little reason to prnble. His long-awaited biography of icrioanTrsoavYe MacDonald ald is a success, albeit a o and I'vtarquand's amiable, b:"se and slightly boyish features have t, en exposed recently in the media more _Ilan they ever were over some inter-party 4bqotlabb1e. Marquand enjoyed writing the He is a genuinely natural writer,' says ::iaekintosh. Its very difficulties gave him r the academic challenge he enjoys. 'A biog_a PhY. brings problems. You don't know the 'questions until you find out the answers.

That takes time.' On this he is unrepentant and finally admits that 'if I had to choose between having written old Ramshackle and office I'd choose the former.'

Privately, David Marquand is not a dramatic person. 'He's well organised,' says Mackintosh, 'he's extremely fond of his children and has a very happy marriage.' His wife Judith is a long-time civil servant at the Treasury and a considerable intellectual in her own right. 'I remember when they were engaged at Oxford,' recalls Richard. 'They were obviously in love but would argue for hours on the phone about some obscure point of economic or political doctrine. We all fell about.' Nothing has changed. 'When they stay with us in Wales they'll walk for hours across the countryside, arguing amicably in and out of bogs and things.' Richard admits David is perhaps not 'pushy' enough for high politics. 'I know it sounds boring, but we really did have a very stable childhood. Perhaps that's a disadvantage fora politician. Most of them

seem to have had quite dreadful times.' Another thing about David is that he doesn't care about image. He loves acting though, he's very good, loves dressing up as dozy charladies and randy vicars and things.'

Such harmless exhibitionism, though endearing, is hardly adequate to propel any politician to the"top. Marquand is arrogant about his writing. 'The joy of writing books is that they are you and no one can take that away, but, except in argument, he is not ruthless. He is too much of a Whig, too wellrounded to enjoy what he describes as the 'sham battles' and 'petty partisan abuse' that characterise much of current British politics. An Oxford friend and parliamentary colleague, still hanging on, says of Marquand: 'He has one of the best minds in the Labour Party, but he lacks the passion that whips the blood.' Brussels should suit him. There will be no lack of the intelligent companionship and good living that he enjoys, and Brussels is not a passionate place.

Previous page

Previous page