THE TORTOISE LEFT BEHIND

Diana Geddes reports that M. Barre is

losing an election race in which style comes before content

Paris AT EVERY election — and there are a lot in France — the French always complain that they are bored, and this time is no exception. But the talk at dinner tables is of little else, and it is impassioned.

Precisely because this is an election of personalities rather than issues, people are much more interested than usual. The power struggle that is going on among three such colourful and intelligent perso- nalities is after all much more fascinating, if one is honest, than a discussion of the finer points of tax reform or new ways of controlling unemployment.

With just over a week to go before the first round of the presidential election on 24 April, President Mitterrand is still com- fortably in the lead, though the latest polls indicate that M. Jacques Chirac, the neo- Gaullist prime minister, may be beginning to close the gap.

During the months of mock suspense leading up to M. Mitterrand's tardy dec- laration of his candidacy on 22 March, everyone had predicted that he would lose support once he stepped down from the prestigious heights of his presidential office and muddied his hands in the political arena. But that has not happened.

All the polls show M. Mitterrand as holding his own with around 37-39 per cent of the vote in the first round, compared with 24-27 per cent for M. Chirac, a mere 15-17 per cent for M. Raymond Barre, the centre-right candidate, and an unexpected- ly commendable 11-12 per cent for M. Le Pen, leader of the extreme-right National Front. In the second round, M. Mitterrand is still seen as capable of defeating any challenge.

One of the surprises of the campaign has been the collapse of the Barre vote. Four months ago, he was seen as the clear leader of the Right. Now he is considered as effectively out of the running. Only some major upheaval such as a new stock market crash or an international crisis, which would bring his very real qualities to the fore, could save him.

The dearth of serious political debate has hurt M. Barre. The electorate, disillu- sioned by past broken promises of both Right and Left, no longer seems interested in detailed manifestos or ready-made prog- rammes. Besides, all the main candidates' proposals sound remarkably similar — less unemployment, a more unified Europe, better education, increased business incen- tives, more help for the poor.

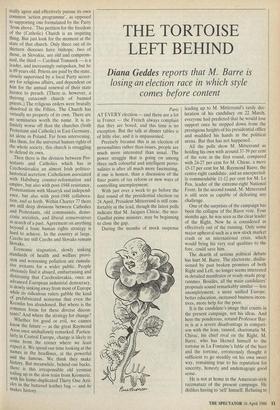

It is the candidate's image that counts in the present campaign, not his ideas. And here the ponderous, rotund Professor Bar- re is at a severe disadvantage in compari- son with the lean, tanned, charismatic M. Chirac, his chief rival on the Right. M. Barre, who has likened himself to the tortoise in La Fontaine's fable of the hare and the tortoise, erroneously thought it sufficient to go steadily on his own sweet way, remaining true to his reputation for sincerity, honesty and undemagogic good sense.

He is not at home in the American-style razzmatazz of the present campaign. He dislikes having to 'sell' himself. Refusing to 'play the fool', as he puts it, he has persisted in conducting a sober, not to say austere, campaign. He has neither the devoted backing nor the wealth of M. Chirac's superbly well-oiled RPR party machine.

'I've never been able to resign myself to considering myself as some brand of washing powder,' he said ruefully recently. 'I have too much esteem for my fellow countrymen to believe that they would base their choice on a wheedling smile or a deep tan [a dig at M. Chirac] or a village spire [a jab at M. Mitterrand's 'force tranquille' image] . . . I believe they want serious replies to serious questions.' But the polls are proving him wrong.

On the other hand, the inclUatigable M. Chirac has always loved the campaign trail. He is terribly good at chatting with farmers over a `gros rouge' or kissing pretty girls. At the superbly stage-managed mass meet- ings of the party faithful, which often more resemble a rock concert than a serious political gathering, he fits perfectly the role of the adulated idol. On television — his former weak point — he has learnt to be calmer, more effective and relaxed.

His image-makers have done a good job. The new-look Chirac smiles seductively out of his campaign posters, gazing deep into the voter's eyes. Gone are the severe, square, black-rimmed spectacles; gone is the jutting, aggressive jaw. Here is a younger, softer, supposedly truer Chirac whose qualities of 'courage, ardour and will-power' the posters extol, and with whom the electorate is invited 'to go further together' along the road the gov- ernment has taken over the past two years.

M. Barre's efforts are by contrast la- mentable. His campaign posters make him look, stuffy, pudgy and old-fashioned. Although only seven years older than M. Chirac, he appears to belong to a different generation. In order to ensure maximum support for the surviving right-wing candi- date in the second round, he and M. Chirac agreed to avoid making too clear their political difference with the result that many people are now left wondering why they should vote for Barre when they could get more or less the same thing by voting for the more dynamic M. Chirac.

. Mitterrand is not exactly young or good-looking either, but he fascinates and intrigues in a way that M. Barre has never done. He is also a more accomplished orator and a much better tactician. He can play the political register as no one else in France today, and is capable of changing his political habits at will. Once dubbed the Sphinx,, he is now becoming better known as the chameleon.

Either the French have remarkably short memories or they are more willing than other nations to forgive their politicians' mistakes. Having detested M. Mitterrand while the socialists were in power — M. Mitterrand reached a record of unpopular- ity for any Fifth Republic president in 1984 — a majority now consider that the five- '1 wonder if you could read these notes I've made about you — I can't understand my own handwriting.' year period of socialist rule was an overall good thing for the country and that the new-style moderate, reasonable, almost affable M. Mitterrand is after all a fine fellow.

Astonishingly, no mention has been made . in the present campaign of M. Mitterrand's involvement with the murky Greenpeace affair; of his autocratic deci- sion to hand over France's first private television channel to one of his friends and the Italian 'spaghetti' television magnate, Silvio Berlusconi; of his invitation to Gen- eral Jaruzelksi, the Polish leader, to visit France in 1985 without even bothering to infornh, let alone consult, his own prime minister; of his highly controversial choice of a glass pyramid as the entrance to the new, enlarged Louvre without even discus- sing the plan.

hi the first five years of his presidency, M. Mitterrand took more power into his own hands than any president before him. Yet now, in his 26-page 'Letter to the French People', which he has produced in lieu of a manifesto, he insists that a president should not interfere in the day- to-day running of the country, but should rather act as a kind of wise umpire, laying down broad, guidelines, particularly in de- fence and foreign policy, but otherwise leaving the government to govern as he has done during the past two years of forced 'cohabitation' with M. Chirac.

It is an eloquent, simply written docu- ment, peppered with withering criticism of M. Chirac, and full of fine sentiments about peace and disarmament, the Third World, the poor, immigrants, the young and the marvellous opportunities of a united Europe. But every time it comes to details as to how such a measure would be implemented or paid for, M. Mitterrand simply says that these technicalities are the business of governments, not presidents.

It is a document which is designed to attract the moderate, centrist vote, while avoiding alienating the left-wing vote. The more controversial parts of the socialists' former programme are dropped; there will be no more nationalisations at present; private Catholic schools are apparently no longer threatened; businesses, but not private individuals, will have their taxes reduced. At the same time, sops are thrown to the Left in the form of a re-introduction of the wealth tax and guaranteed minimum income for the poor.

Despite M. Mitterrand's personal popu- larity, the polls indicate that the Right still has substantial majority support in the country. M. Mitterrand has said that if he is re-elected, he will immediately appoint a prime minister to form a new government sympathetic to his cause. Only if that government fails to win the support it needs in the present right-wing-dominated parliament will he dissolve parliament and call new elections. In either case, he must win centrist support if he is to avoid a new period of political 'cohabitation'.

Previous page

Previous page