ARTS

Theatre

The Common Pursuit (Phoenix) Danger: Memory! (Hampstead)

Fashion (Pit)

When the past catches up

Christopher Edwards

Simon Gray has so transformed The Common Pursuit that it is hardly recognis- able as the, play that fared so badly at the Lyric Hammersmith a few years. ago. It is fresher, far funnier, more touching than before, and seems set for a long, successful run in the West End.

The piece follows the lives of five Cam- bridge men and one woman — Stuart, Martin, Humphry, Nick, Peter and Mari- gold — from the moment of their first meeting to form an undergraduate literary magazine down through various stages in their careers 20 years and several mar- riages, businesses and unwritten books later. The cast — made up of young comedians and comic actors — is first-rate. John Sessions's Stuart is a poignant and scrupuloui study. The magazine is his creation, he nurses it after graduating and then suffers a series of reversals. Abandon- ing the magazine to, have children with Marigold (Sarah Berger), he learns first that he is sterile, then that he has been cuckolded by the bland, talentless Martin (Paul Mooney). John Gordon Sinclair is the rake of the group, sliding into an Oxford fellowship before his betters realise that a first-rate mind has been subordin- ated to carnal pursuits.

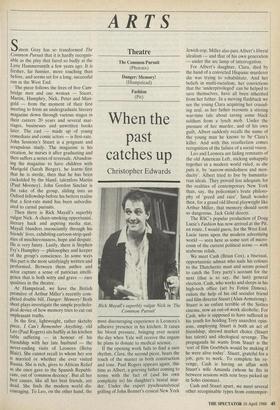

Then there is Rick Mayall's superbly vulgar Nick. A chain-smoking opportunist, literary hack and aspiring media star, Maya11 blunders insouciantly through his friends' lives, exhibiting cartoon-strip qual- ities of mischievousness, hope and despair. He is very funny. Lastly, there is Stephen Fry's Humphry — philosopher and keeper of the group's conscience. In some ways this part is the most satisfyingly written and perfornied. Between them author and actor capture a sense of patrician intelli- gence that is both witty and grave — rare qualities in the theatre.

At Hampstead, we have the ,British premiere of Arthur Miller's recently com- pleted double bill, Danger: Memory! Both short plays investigate the simple psycholo- gical device of how memory tries to cut out unpleasant truths.

. In the first, lightweight, rather sketchy piece, I Can't Remember Anything, old Leo (Paul Rogers) sits huffily at his kitchen table suffering — in honour of his friendship with her late husband — the never-ending visits of Leonora (Betsy Blair). She cannot recall to whom her son is married or whether she ever visited Russia. She is rich, gives to African Relief as she once gave to the Spanish Republi- cans, out of 'common decency'. But all her best causes, like all her best friends, are dead. She finds the modern world dis- couraging. To Leo, on the other hand, the Rick Mayall's superbly vulgar Nick in 'The Common Pursuit' most discouraging experience is Leonora's adhesive presence in his kitchen. It raises his blood pressure, bringing ever nearer the day when Yale will receive the organs he plans to donate to medical science.

If the opening work fails to find a sure rhythm, Clara, the second piece, bears the touch of the master in both construction and tone. Paul Rogers appears again, this time as Albert, a grieving father coming to terms with the fact of (and his own complicity in) his daughter's brutal mur- der. Under the expert pyschoanalytical grilling of John Bennet's cynical New York

Jewish cop, Miller also puts Albert's liberal idealism -- and that of his own generation — under the arc lamp of interrogation.

For, Albert's daughter, Clara, died by the hand of a convicted Hispanic murderer she was trying to rehabilitate. And her beliefs in multi-racialism, her convictions that the 'underprivileged' can be helped to save themselves, have all been inherited from her father. In a moving flashback we see the young Clara acquiring her crusad- ing zeal, as her father recounts a stirring war-time tale about saving some black soldiers from a lynch mob. Under the pressure of her murder, and of his own guilt, Albert suddenly recalls the name of the young man he knows to be Clara's killer. And with this recollection comes recognition of the failure of a social vision.

Leo and. Leonora are fading remnants of the old American Left, sticking unhappily together in a modern world rifled, as she puts it, by 'narrow-mindedness and men- dacity'. Albert tried to live by liumanita7 rian ideals. They proved less adequate for the realities of contemporary New York than, say, the policeman's brute philoso- phy of 'greed and race'. Small wonder then, for a grand old liberal playwright like Arthur Miller, that memory should seem so dangerous. Jack Gold directs.

The RSC's popular production of, Doug Lucie's Fashion has now arrived, at the Pit, en route, I would guess., for the West End. Luck turns upon the modern advertising world — seen here as some sort of micro- cosm of the current political scene — with scabrous relish.

We meet Cash (Brian Cox), a bisexual, opportunistic adman who nails his colourS to the Thatcherite mast and seems poised to catch the Tory party's account for the next (that is to say, the last) general election. Cash, who works and sleeps in his high-tech office (set by Fotini Dimou), enlists the help of his old socialist friend and film director Stuart (Alun Armstrong). Stuart is an enfant terrible of the Sixties cinema, now an out-of-work alcoholic. For Cash, who is supposed to have suffered in his youth for holding.Tory anarchist opin- ions,_ employing Stuart is both an act of friendship, shrewd market choice (Stuart has talent) and ideological revenge. The propaganda he wants from Stuart is the 'sort of film Goebbels would be making if he were alive today'. Stuart, grateful for a job, gets to work.. To coimilete his re- venge, Cash is having an 'affair with Stuart's wife Amanda (whom he fits in between sessions with rent boys picked up in Soho cinemas).

Cash and Stuart apart, we meet several other recognisable types from contempor- ary public life. They include Eric Bright, a former Labour MP turned smoothy Thatcherite media pundit (Clive Russell); he comes complete with pin-stripe suit, user-friendly telly-gestures and phrases like, 'I'm leaving for a fact-finding freebie for the colour supp'. Then there is the prize satirical turn of the evening, Gillian Hunt- ley (Linda Spurrier), prospective Tory candidate and robotic copy (heavily foxed) of the Prime Minister.

Lucie's talent for composing vividly heightened passages of contemporary life is matched by a rhetorical flair that calls to mind, in the first half at least, the young John Osborne. But the play suffers from sententiousness, is too long (we lose in- terest in the rather stagy series of set speeches at the end) and betrays its cool incisiveness by sentimentally coming down in favour of a happy, let's-give-it-another- try ending for Stuart and his wife Amanda.

Previous page

Previous page